Indonesian Hajj Cohorts and Mortality in Saudi Arabia from 2004 to 2011

- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.181231.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Mass gathering; cohort study; pilgrim

- Abstract

The Hajj is an annual pilgrimage that 1–2 million Muslims undertake in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), which is the largest mass gathering event in the world, as the world’s most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia holds the largest visa quota for the Hajj. All Hajj pilgrims under the quota system are registered in the Indonesian government’s Hajj surveillance database to ensure adherence to the KSA authorities’ health requirements. Performance of the Hajj and its rites are physically demanding, which may present health risks. This report provides a descriptive overview of mortality in Indonesian pilgrims from 2004 to 2011. The mortality rate from 2004 to 2011 ranged from 149 to 337 per 100,000 Hajj pilgrims, equivalent to the actual number of deaths ranging between 501 and 531 cases. The top two mortality causes were attributable to diseases of the circulatory and respiratory systems. Older pilgrims or pilgrims with comorbidities should be encouraged to take a less physically demanding route in the Hajj. All pilgrims should be educated on health risks and seek early health advice from the mobile medical teams provided.

- Copyright

- © 2019 Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Over 1–2 million Muslims globally partake in the annual Hajj pilgrimage to and in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) [1]. This is the largest annual global temporary migration and gathering of Muslims during a short period. The largest Hajj quota is allocated to Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim nation. Performance of the Hajj and its rites are physically demanding, together with overcrowding owing to the large number of pilgrims. Health risks during the Hajj include sun exposure, extreme temperatures (depending on the season when the Hajj falls—summer or winter), dehydration, crowding, steep inclines, and traffic congestion [2–5]. As the Hajj is fairly expensive for pilgrims from Indonesia, a middle-income developing country, the pilgrims tend to be older with medical comorbidities [2,6], which may increase the risk of severe infections especially influenza [7], Neisseria meningitis [8], gastroenteritis [9], cardiovascular, [10,11], and respiratory episodes [12]. Furthermore, there is also the probability of stampedes in certain areas despite several measures taken by the KSA authorities [5]. Iran is one of the very few countries that have published pilgrim morbidity [13] and mortality rates on a cohort basis [14]. A study of Iranian pilgrims over a 2-year period estimated a mortality rate of 47 per 100,000 pilgrims in 2004, whereas it was 24 per 100,000 pilgrims in 2005 [14]. However, compared with the available information, the Indonesian mortality rate is much higher [10].

An estimated 98% of Indonesians perform the Hajj once in their lifetime, due to cost and priority allocation for first time Hajj pilgrims. The Hajj’s period follows the lunar calendar, so that sometimes it falls between spring/summer (extreme heat) and autumn/winter seasons (extreme low temperatures) in the arid desert climate of Mecca and Medinah [15]. This report uses data extracted from the Indonesian Hajj surveillance to provide a descriptive overview of mortality patterns in each cohort of pilgrims from 2004 to 2011 (winter Hajj season) to identify health issues of pilgrims for further research planning.

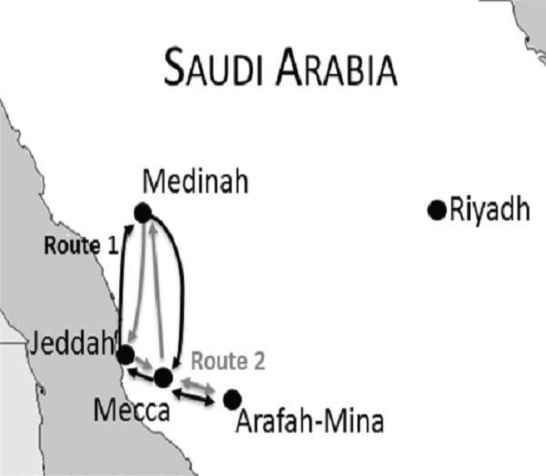

The duration of the government-sponsored travel for pilgrims to the KSA is 40 days, of which 22 days are spent in Mecca, 5–6 days in Arafat-Mina, 8–9 days in Medinah, and 1–2 days in Jeddah (for transit). There are two routes available to pilgrims who may travel from 12 airports within Indonesia (Figure 1). Route 2 is more physically demanding as pilgrims proceed to Mecca directly after a long flight (∼10 hours or more) and then to Arafat-Mina. Route 1 is less demanding as pilgrims can stop over in Jeddah/Medinah after the flight prior to the 2-hour journey to Mecca.

Travel routes (Routes 1 and 2) for Indonesian pilgrims, with the arrival in and departure from Jeddah (adapted from Pane, et al. [10])

Since 1950, medical services have been provided by the Government of Indonesia to their Hajj pilgrims. Some services, such as predeparture health screening, meningococcal vaccination as well as temporary clinics staffed by Indonesian doctors in the KSA, have been introduced progressively over the years. For all pilgrims >40 years old, tuberculosis (TB) screening is done additionally by any registered medical doctor or general practitioner prior to departure from Indonesia. This is because Indonesia has a high burden of TB [10].

For the Hajj [10], there is specialised surveillance conducted for morbidity and mortality in Hajj pilgrims by a team of doctors and nurses who accompany the pilgrims to Saudi Arabia. The purpose of this surveillance is to identify possible interventions for mortality reduction and assist in life insurance claims [10]. The surveillance begins from the moment the pilgrims leave their residence to embark on their journey until they return home or they pass away. There is a 14-day follow-up after they return to Indonesia if an infectious disease is detected in either KSA or Indonesian healthcare facilities. The surveillance data hold individual records of pilgrim demographics, hospitalisation, morbidity, and mortality data coded according to the broad International Classification of Diseases (currently ICD-10) coding due to limited resources in KSA to do a full autopsy. Reports of hospitalisations and deaths are recorded either by hospital death certificate (issued by KSA) or general cause of death (with verbal autopsy results since 2008). Verbal autopsy allows for the systematic investigation of probable causes of death where only a fraction of deaths occur in hospitals or in absence of vital registration systems. All these reports are sent daily to a central Indonesian public health team based in KSA during the Hajj. The data obtained from Hajj medical service records also include hospital death certificates or flight doctor’s records if a death occurred in the community. Demographic variables collected include name, age, sex, home address, employment, flight group, travel route, date of arrival into Saudi Arabia, and cause of death (if any), according to the hospital medical record or flight doctor death certificate.

Prior to departure, pilgrims have to undergo a medical test to confirm that they are fit for travel and to receive the meningococcal vaccine as mandated by the Saudi Arabian authorities. They are also advised to receive the influenza vaccine with the exception of 2009 where all pilgrims had to receive both meningococcal and influenza vaccine due to the pandemic (H1N1).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Population

In 2004–2011, >1.6 million Indonesians undertook the pilgrimage during Hajj. The pilgrims who joined one of the government-sponsored Hajj pilgrimage travel services had 40 days of travel. All the pilgrims were divided into 480–500 flight groups, the minimum number of pilgrims in each flight group was 355 pilgrims, and the maximum was 455 pilgrims. One doctor and two nurses accompanied each flight group and conducted health services, except in 2005–2006, when there was only one doctor and one nurse in the flight group.

2.2. Health Services and Surveillance

Public health surveillance was conducted as the morbidity and mortality surveillance in Hajj by the Indonesian public health authorities accompanying pilgrims to Saudi Arabia with daily reporting of hospitalizations and deaths. One Indonesian doctor and two nurses accompanied each flight group of ∼350–400 pilgrims to conduct morbidity and mortality surveillance. For deaths, the Indonesian public health team maintains a database of demography, hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality data. Data were obtained from the Hajj medical service records such as the hospital death certificate or the flight doctor’s records if a death occurred in the community. Database variables included name, age, sex, home address, employment, flight group, travel route, date of arrival into Saudi Arabia, and cause of death as obtained from the hospital medical record or flight doctor’s death certificate.

Predeparture, pilgrims undertake a medical test to confirm fitness-for-travel and to receive a meningitis vaccine. Pilgrims who were aged >60 years and had at least one preexisting medical condition (e.g., diabetes mellitus, heart conditions, hypertension) were classified as high risk. For the purpose of this study, they were categorized into the high-risk group. Pilgrims were mandated to receive meningococcal vaccines and were advised to receive the influenza vaccine before their departure. These healthcare workers treated, triaged, and conducted health surveillance for pilgrims. Hospitalizations and any incidental deaths occurring outside a healthcare facility were notified daily to the Indonesian public health team based in Saudi Arabia.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Mortality data collected by the Indonesian public health team were entered into a database for data analysis. Standard variables in the database included name, age, sex, home address, employment, flight group, time and place of death, date of arrival into Saudi Arabia, and cause of death as per the hospital or flight doctor’s death certificate.

We used counts and proportions to describe demographic characteristics of Indonesian pilgrims and fatalities. The description for the trend was used for the analysis of categorical and numerical data. To show the consistency of the data by years, we compared the percentages and rates for each variable and used logistic regression to analyze factors associated with deaths outside health services. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Ministry of Health (MOH), National Institute of Health Research and Development ethics review committee with the approval number LB.03.04/KE/4687/2008.

3. RESULTS

Each year, from 2004 to 2011, ∼200,000 Indonesians joined Hajj (Table 1). All pilgrims were aged ≥18 years and the majority (53.0–59.0%) were aged between 40 and 60 years. Most pilgrims were female (55.0%). One-fifth of Hajj pilgrims had higher education and the majority of them were business employees and housewives. According to the pre-embarkation medical assessment, 27.0–43.4% of pilgrims were classified as high risk due to underlying health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, other chronic diseases, or if they were aged 60 years or older. The top two causes of mortality were diseases of the circulatory system (cardiovascular disease) and those of the respiratory system. Both contribute 44.9–66.0% and 24.9–33.4% of deaths from 2004 to 2011, respectively (Table 1).

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Hajj pilgrims | 205,732 | 203,608 | 205,185 | 191,822 | 206,831 | 211,351 | 222,930 | 222,560 | 208,752 |

| Male pilgrims (%) | 44.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.1 | 45.1 | 45.3 | 45.0 | 45.2 | 45.0 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| Mean (Min–Max) | 62.5 (28–92) | 64.8 (24–92) | 65.3 (16–92) | 64.6 (28–92) | 65.6 (20–90) | 64.7 (32–90) | 65.4 (40–95) | 66.1 (35–92) | 64.9 (16–95) |

| Age group (%) | |||||||||

| ≤40 years old | 29.0 | 29.1 | 23.5 | 22.7 | 20.0 | 20.8 | 13.2 | 16.3 | 21.8 |

| 41–50 years old | 30.5 | 31.3 | 30.6 | 30.2 | 29.0 | 29.8 | 26.5 | 28.6 | 29.6 |

| 51–60 years old | 23.5 | 23.4 | 25.9 | 26.7 | 29.0 | 28.5 | 32.4 | 31.3 | 27.6 |

| 61–70 years old | 13.3 | 12.8 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 17.7 | 15.0 | 12.9 | 16.8 | 15.0 |

| >70 years old | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 15.0 | 7.0 | 6.1 |

| Education (%) | |||||||||

| Primary/illiterate | 34.0 | 31.2 | 33.4 | 34.3 | 34.4 | 34.6 | 23.6 | 36.1 | 32.7 |

| Secondary | 44.2 | 45.3 | 42.2 | 41.1 | 41.0 | 39.6 | 25.4 | 36.7 | 39.4 |

| Higher education | 21.8 | 23.4 | 24.4 | 24.7 | 24.6 | 25.8 | 17.3 | 27.2 | 23.7 |

| Occupation (%) | |||||||||

| Farmer | 11.2 | 9.2 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 10.4 | 13.8 | 11.8 |

| Civil servant | 19.7 | 20.0 | 19.1 | 16.6 | 18.1 | 18.0 | 17.2 | 19.0 | 18.5 |

| Army | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Housewife | 31.5 | 30.8 | 30.3 | 29.6 | 28.6 | 29.1 | 30.7 | 28.5 | 29.9 |

| Students | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Business employee | 34.5 | 35.3 | 33.6 | 34.5 | 33.1 | 32.8 | 31.3 | 31.1 | 33.3 |

| High health risk (%) | 41.3 | 34.1 | 27.6 | 31.7 | 28.3 | 38 | 39.1 | 43.4 | 35.4 |

| Number of deaths | |||||||||

| Jeddah | 23 | 22 | 25 | 27 | 25 | 19 | 21 | 28 | 24 |

| Medinah | 60 | 91 | 89 | 70 | 82 | 55 | 69 | 69 | 73 |

| Mecca | 325 | 291 | 506 | 320 | 306 | 224 | 315 | 374 | 333 |

| Arafah-Mina | 91 | 32 | 43 | 38 | 33 | 14 | 23 | 32 | 38 |

| Travel | 2 | 1 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 28 | 9 |

| Total | 501 | 437 | 676 | 462 | 446 | 312 | 451 | 531 | 477 |

| Death rate per 100,000 pilgrims | 243.5 | 214.6 | 329.5 | 240.9 | 215.6 | 147.6 | 202.3 | 238.6 | 229.0 |

| Number of flight groups | 480 | 480 | 486 | 469 | 485 | 486 | 501 | 496 | 485 |

| Number of flight health workers per flight groupa | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of health officers at Indonesian clinics | 83 | 83 | 248 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 |

Not including provincial or district health worker.

Demographic characteristics and healthcare provision for Indonesian Hajj pilgrims from 2004 to 2011

The mortality rate for the mentioned 8 years ranged from 149 to 337 per 100,000 Hajj. Most deaths occurred in Mecca, followed by Medinah and Jeddah (Table 1). It is mainly because of different periods of stay: Mecca (23 days), Medinah (8.5 days), and Jeddah (24 hours). Figure 2a shows deaths during the entire years according to age and sex; as age increased, the proportion of male deaths increased. The proportion of female deaths are higher in individuals less than 50 years of age, but 70% of deaths were among males aged ≥70 years. There were reports of women between the ages of 35 and 60 years who were diagnosed in KSA with a terminal illness. Although the doctors’ reports were checked generally before departure, this group slipped through the net. This will need to be investigated further and to determine whether stricter checks need to be in place.

Characteristics and timing of deaths (a) by age and sex, (b) weekly mortality during the Hajj, (c) cumulative deaths per 100,000/year; and (d) by hour of the day

Thus, the proportion of female deaths is skewed due to this underlying factor. This trend may change in the future as the pilgrim queue system has changed. During 2004–2011, terminally ill individuals could be provided priority Hajj opportunity. However, in more recent years, the queue system is less flexible to provide priority to the terminally ill. Weekly mortality rates exceeded the expected crude mortality rate in week 6 when most pilgrims were in Mecca, and it remained high until the end of Hajj 4 weeks later. The weekly mortality rate was greater in 2006 compared with those in all other years (Figure 2b). Policlinic Maktab (in 2006) was an experimental approach to centralizing healthcare workers in Mecca so that pilgrims could go to a center rather than access the healthcare provided by the workers nearby. As can be seen from Table 1, the number of deaths (n = 506) in 2006 in Mecca was very high (30% more than those in other years).

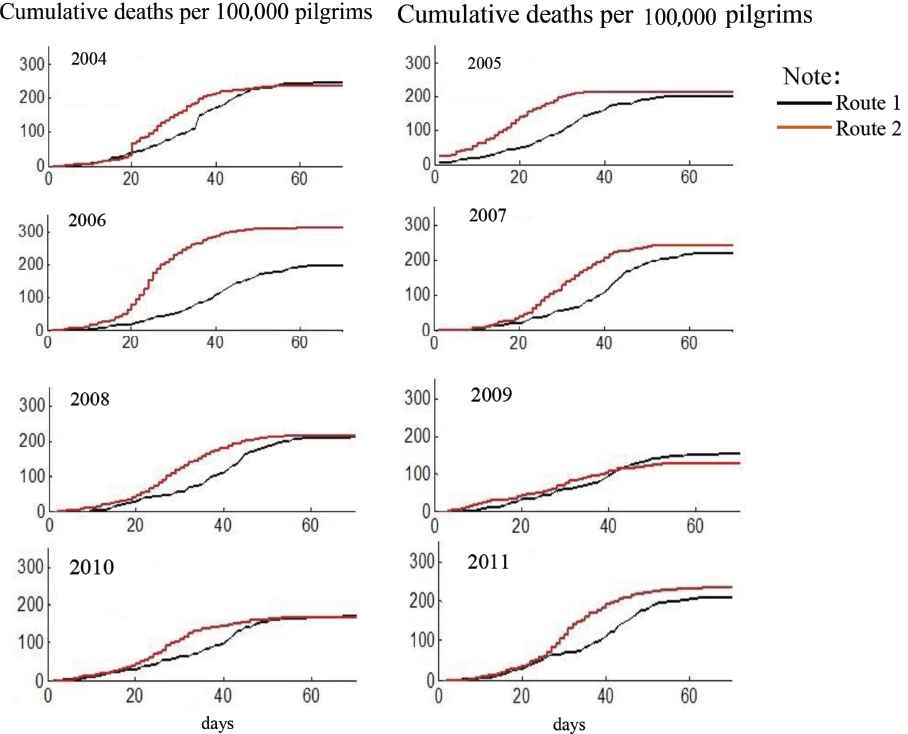

Mortality rates for pilgrims travelling on Route 2 peaked earlier during the Hajj period than those travelling on Route 1 (Figure 2c). This is likely due to less time for acclimatization to the surrounds, heat, and the intense physical activity during Hajj. Figure 2d shows the risk of death per 100,000 pilgrims hour-by-hour throughout the day for 2004 and all other years combined. In 2004, a stampede occurred that led to mass causalities during the middle of the day. This is indicated by the spike in deaths at 12 noon in 2004. Figure 3 shows death rate from the time of arrival for Routes 1 and 2 and for each year. Route 2 consistently peaks earlier than Route 1. This highlights the need to instigate more public health interventions for Route 2 on their arrival. This may include predeparture health education and physical preparation. The same pattern was observed in each year except in 2009, wherein no difference was observed. There was a stampede situation in Mina Tunnels, which caused >200 Hajj deaths at that time.

Cumulative deaths per 100,000 pilgrims from the time of arrival for Routes 1 and 2 and for each year from 2004 to 2011

One of the success indicators for health services is that 40% of deaths should not occur outside the healthcare facilities. The average of proportion of deaths occurring outside healthcare facilities was 41.2%, there was a decreasing trend in that proportion (Table 2). A large proportion of deaths outside healthcare facilities occurred during weeks 4–7. This is during the peak time of Hajj season, when crowding and physical activity are most intense.

| Category | 2004 (n = 501) (%) | 2005 (n = 437) (%) | 2006 (n = 676) (%) | 2007 (n = 462) (%) | 2008 (n = 446) (%) | 2009 (n = 312) (%) | 2010 (n = 451) (%) | 2011 (n = 531) (%) | Average (n = 3816) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-10 cause of death | |||||||||

| Neoplasms (C00–D49) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (1.3) | 8 (1.7) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (0.6) | 7 (1.6) | 8 (1.51) | 43 (1.1) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system (I00–I99) | 231 (46.1) | 196 (44.9) | 387 (57.2) | 242 (52.4) | 292 (66.0) | 194 (62.2) | 242 (53.7) | 314 (59.1) | 2098 (55.0) |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (E00–E89) | 8 (1.6) | 7 (1.6) | 17 (2.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 10 (2.2) | 10 (1.9) | 57 (1.5) |

| Diseases of the digestive system (K00–K95) | 11 (2.2) | 9 (2.1) | 13 (1.9) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 9 (2.0) | 10 (1.9) | 60 (1.6) |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system (N00–N99) | 7 (1.4) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (0.7) | 14 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.1) | 7 (1.3) | 45 (1.2) |

| Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism (D50–D89) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (0.5) |

| Certain infectious and parasitic diseases (A00–B99) | 3 (0.6) | 8 (1.8) | 5 (0.7) | 14 (3.0) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (1.0) | 25 (5.5) | 20 (3.8) | 80 (2.1) |

| Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not classified elsewhere (R00–R99) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (0.3) |

| Diseases of the nervous system (G00–G99) | 24 (4.8) | 22 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 15 (3.3) | 6 (1.4%) | 0 (0) | 25 (5.5) | 26 (4.9) | 118 (3.1) |

| Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium (O00–O9A) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders (F01–F99) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.1) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system (J00–J99) | 133 (26.6) | 146 (33.4) | 195 (28.9) | 118 (25.6) | 126 (28.0) | 104 (33.3) | 115 (25.5) | 132 (24.9) | 1069 (28.0) |

| Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes (S00–T88) and external causes of morbidity (V00–Y99) | 64 (12.8) | 7 (1.6) | 8 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | 91 (2.4) |

| Other ICD-10 codes | 18 (3.6) | 30 (6.9) | 18 (2.7) | 45 (9.7) | 6 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 122 (3.2) |

| Route | |||||||||

| 1 | 230 (45.9) | 183 (41.9) | 293 (43.3) | 189 (40.9) | 200 (44.8) | 146 (46.8) | 173 (38.4) | 212 (39.9) | 1626 (42.6) |

| 2 | 268 (53.5) | 240 (54.9) | 360 (53.3) | 255 (55.2) | 246 (55.2) | 146 (46.8) | 207 (45.9) | 289 (54.4) | 2011 (52.7) |

| ONH plus (Special group) | 3 (0.6) | 14 (3.2) | 23 (3.4) | 18 (3.9) | No data | 20 (6.4) | 71 (15.7) | 30 (5.7) | 179 (4.7) |

| Place of death | |||||||||

| Airport | 3 (0.6) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (2.2) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 30 (0.8) |

| Ambulance | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (3.8) | 25 (0.7) |

| KSA-based clinic for Indonesian pilgrims | 81 (16.2) | 72 (16.5) | 199 (29.4) | 77 (16.7) | 95 (21.3) | 77 (24.7) | 79 (17.5) | 73 (13.8) | 753 (19.7) |

| Flight | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | 7 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 11 (2.4) | 7 (1.3) | 38 (1.0) |

| Mosque | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 7 (1.5) | 6 (1.4) | 9 (2.9) | 5 (1.1) | 9 (1.7) | 43 (1.1) |

| Others | 0 (0) | 17 (3.9) | 42 (6.2) | 19 (4.1) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.1) | 86 (2.3) |

| Mina | 53 (10.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 53 (1.4) |

| On route | 18 (3.6) | 13 (3.0) | 16 (2.4) | 1 (0.2) | 12 (2.7) | 21 (6.7) | 23 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 104 (2.7) |

| Lodging | 160 (31.9) | 170 (38.9) | 228 (33.7) | 170 (36.8) | 161 (36.1) | 76 (24.4) | 155 (34.4) | 169 (31.8) | 1289 (33.8) |

| Hospital (KSA) | 181 (36.1) | 156 (35.7) | 176 (26.0) | 181 (39.2) | 160 (35.9) | 121 (38.8) | 174 (38.6) | 246 (46.3) | 1395 (36.6) |

| Death outside of health service | 239 (47.7) | 209 (47.8) | 301 (44.5) | 204 (44.2) | 191 (42.8) | 114 (36.5) | 198 (43.9) | 211 (39.7) | 1667 (43.7) |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases; KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; ONH plus, Hajj services with extra services provided by the private sector.

Cause and place of death

Significantly higher number of deaths occurred in healthcare facilities in Mecca. This is likely due to the availability of seven free Saudi hospitals in Mecca as well as the Indonesian-managed healthcare facilities. The Indonesian-managed healthcare facilities include a hospital (Balai Pengobatan Haji Indonesia/BPHI) and ∼11 satellite healthcare facilities on average over the duration of the study. Majority of deaths occurring in healthcare facilities in Mecca were in Saudi Arabian Hospital (Rumah Sakit Arab Saudi/RSAS) (n = 967, 25.3%) and the remainder (n = 604, 15.8%) occurred in Indonesian-operated health services. The MOH aims to decrease the proportion of deaths occurring outside healthcare facilities. Each year, there is an investment in raising pilgrim awareness to seek early treatment and to ensure the availability of health services. The program has successfully reduced the proportion of deaths occurring outside healthcare facilities.

Multivariate analysis shows that deaths occurring outside healthcare facilities were more likely in Mecca for both sex groups {adjusted odds ratio (aOR) male group = 2.49 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.75–3.55] and female group 1.80 [95% CI: 1.14–2.85]}, and causes of deaths as communicable diseases in the male group [aOR = 4.08 (95% CI: 2.51–6.64)] or trauma/injury-related in the female group [aOR = 4.11 (95% CI: 2.25–7.52)]. During Hajj, fewer deaths outside healthcare facilities occurred in the later weeks (Table 3) and fewer deaths occurred outside healthcare facilities in Mecca.

| Variables | Male | p* | Female | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa (95% CI) | ORb (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ORb (95% CI) | |||

| Years | 1.04 (1.0–1.08) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 0.138 | 1.06 (1.01–1.10) | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.123 |

| Weeks | ||||||

| 1–3 | 1.57 (1.13–2.17) | 1.68 (1.17–2.40) | 0.005 | 1.55 (1.05–2.30) | 1.51 (0.97–2.36) | 0.069 |

| 4–5 | 1.18 (0.93–1.50) | 1.11 (0.86–1.43) | 0.409 | 1.54 (1.15–2.07) | 1.25 (0.91–1.73) | 0.165 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| 7 | 1.28 (1.01–1.62) | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) | 0.768 | 1.55 (1.16–2.08) | 1.14 (0.82–1.57) | 0.433 |

| 8–9 | 1.89 (1.45–2.46) | 1.75 (1.31–2.35) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.41–2.68) | 1.60 (1.11–2.31) | 0.011 |

| 10+ | 13.6 (5.40–34.25) | 12.63 (4.9–32.55) | <0.001 | 13.7 (4.15–45.43) | 12.21 (3.48–42.87) | <0.001 |

| Location | ||||||

| Arafah-Mina | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| Jeddah | 2.91 (1.79–4.73) | 1.92 (1.13–3.26) | 0.016 | 1.92 (1.06–3.46) | 0.82 (0.42–1.60) | 0.558 |

| Medinah | 2.88 (1.97–4.19) | 1.77 (1.16–2.70) | 0.008 | 3.45 (2.17–5.48) | 1.54 (0.88–2.67) | 0.128 |

| Mecca | 2.87 (2.07–3.98) | 2.49 (1.75–3.55) | <0.001 | 3.35 (2.25–4.99) | 1.80 (1.14–2.85) | 0.012 |

| Travel | 1.43 (0.7–2.92) | 0.96 (0.44–2.06) | 0.911 | 1.78 (0.82–3.83) | 0.64 (0.26–1.55) | 0.324 |

| Causes | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| Respiratory disease | 1.88 (1.55–2.28) | 1.93 (1.58–2.35) | <0.001 | 2.82 (2.17–3.66) | 2.71 (2.07–3.54) | <0.001 |

| Others | 1.81 (1.34–2.45) | 1.97 (1.44–2.71) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.07–0.36) | 0.24 (0.10–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Trauma/injury | 0.53 (0.29–0.99) | 0.71 (0.36–1.37) | 0.306 | 4.13 (2.30–7.42) | 4.11 (2.25–7.52) | 0.002 |

| Communicable diseases | 4.17 (2.58–6.72) | 4.08 (2.51–6.64) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.13–2.28) | 1.60 (1.11–2.29) | 0.011 |

Crude odd ratio;

Adjusted odd ratio;

p for adjusted model only;

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with deaths outside health services

4. DISCUSSION

The period from 2004 to 2011 was selected because Hajj during these years fell within the winter season where temperatures in Mecca are not as extreme as in summer. During the Hajj, there is a period where pilgrims are exposed to the elements of the Arafat desert; hence, heat strokes, especially in summers, might play a role in the cause of death [15]. Furthermore, the crowds during the Hajj period create human traffic congestion, especially in Mina, where stampedes tend to occur. In 2004, a stampede in Mina occurred that led to mass causalities during the middle of the day. More than 200 Hajj pilgrims of different nationalities died in the stampede, and an estimated quarter of the deaths were Indonesians.

Anecdotally, there is also a cultural–religious belief that results in young terminally ill women coming to Hajj prior to their death. Thus, the proportion of female deaths could be possibly skewed due to this underlying factor. Women, especially older ones, were also found to be more likely to present underlying chronic cardiovascular disorder and diabetes compared with men during the Hajj, and thus posing a high risk for the Hajj [3,14,16]. Management of cardiovascular risks, especially relating to other factors (e.g., heat stroke, strenuous activities) for both men and women are required during the Hajj because cardiovascular disease is identified by this and other studies as the most important cause of deaths [14,16–19]. Most health programs tend to target the reduction of disease transmission while neglecting the chronic diseases and comorbidities that may affect the Hajj pilgrims [18]. Respiratory diseases are also another common health problem encountered by Hajj pilgrims in the other studies, and our study also identified this as an important cause of deaths [5,14]. Infectious diseases such as severe pneumonia [12,20], common cold [14], TB [21], meningococcal disease, and influenza could be an issue in mass gatherings, where large crowds assemble [15,22–24]. The surveillance and updated information can inform the preparedness for emerging respiratory diseases such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome. Increased laboratory confirmation of infectious diseases would be helpful to prevent and limit the transmission of such infectious diseases.

Terminally ill individuals were a priority for Hajj opportunity from 2004 to 2011. This trend may change in future as the pilgrim selection system becomes stricter and the priority is no longer allocated to the terminally ill because of changing KSA Hajj regulations.

In 2006, the government of the Republic of Indonesia changed a policy for health services in flight groups. Earlier, there was one medical doctor and two nurses, but in 2006, only one medical doctor and one nurse were assigned to each flight group. In addition, one medical doctor was assigned as health services in “PoliMaktab” (hotel’s clinic) in Mecca. PoliMaktab provided medical services for 7–8 flight groups (3000–4000 Hajj pilgrims). Due to the reduction of staffing during the PoliMaktab intervention, this may be one of the factors which may be attributed to the higher than normal mortality rate in Mecca in 2006. The PoliMaktab intervention ceased after one trial.

Many pilgrim deaths occurred earlier in Route 2 because Route 2 is more physically demanding. Those on Route 2 immediately proceed to Armina after disembarking in Jeddah. The physical level of activity in Armina is high (e.g., walking long distances). After Armina, they proceed straight to Mecca. Pilgrims on Route 1 are able to rest in hotels after disembarking. There is more time to rest and acclimatize to the environment in KSA during their stay in Medina before the main journey to Mecca. Accommodation and infrastructure are less crowded and pilgrimage activities are less physically demanding in Medinah compared with those in Mecca. Based on this finding, pilgrims within the high risk group should be encouraged to select Route 1. This may give them ample time to rest before proceeding to Mecca for the main pilgrimage.

Intervention during weeks 6–7 is needed to ensure that pilgrims seek healthcare early so that deaths outside healthcare facilities can be prevented. Over the years, the KSA government have made improvements on providing healthcare services to pilgrims of all nationalities. In 2009, the KSA MOH prepared 24 hospitals (with a total bed capacity of 4964) and 136 healthcare centers equipped with the latest technology together with 17,609 specialized personnel to provide free healthcare to all pilgrims [25]. There were also increased health security measures implemented by the KSA government to mitigate the impact of the pandemic (H1N1) in 2009. For example, there was a mandate by the KSA authorities for all Hajj pilgrims to get vaccinated against influenza in 2009. The Indonesian government also recommended that pilgrims >65 years old refrain from the Hajj due to the pandemic [26]. These measures could have contributed to the lowest mortality rate in 2009. Different characteristics of the Hajj each year together with different interventional approaches taken by the KSA and Indonesian government might have some effect on the health outcomes of Hajj pilgrims, but cardiovascular and respiratory issues remain important concerns.

The peak of the Hajj season falls between weeks 4 and 7, where crowding and physical activity are most intense. Interventions during these weeks are most needed to ensure that pilgrims seek healthcare early, so that deaths outside healthcare facilities can be prevented. Significantly more deaths were found to occur in healthcare facilities in Mecca. This is likely due to the availability of seven free Saudi hospitals in Mecca as well as the KSA-based Indonesian-operated clinics, specifically for Indonesian pilgrims (one central and on average 11 satellite clinics). The MOH, Republic of Indonesia, aims to decrease the proportion of deaths occurring outside healthcare facilities. Investments have been made annually in raising pilgrim health awareness to seek early treatment and conducting reviews to ensure the availability of health services to Indonesian pilgrims.

A major limitation of this report is that it is the available aggregated data. This is the first time that long-term Hajj health data pertaining to Indonesia from 2004 to 2011 were described in an effort to offer some insight into the risks that Indonesian pilgrims face on the Hajj pilgrimage. The other major limitation is the reporting of deaths under a broad ICD-10 category due to the verbal autopsy methods and hospitalization death certification [10]. However, it does not differ from other reports on pilgrims of different nationalities, which indicate cardiovascular and respiratory diseases as well as other comorbidities as a main cause of Hajj pilgrims’ mortality and morbidity [5,18,27]. The ICD-10 coding used in the cause of death remains an important source of data for Hajj health evaluation. There are other identified sources of individual health data, once linked, that can assist in the identification of potential improvement of the Hajj surveillance database and fill the gaps, which need to be investigated for interventional purposes. This report has provided a preliminary assessment of whether there is a need for health education/advocacy research and measures required to enforce vaccinations. Second, there are studies planned on analyzing the effectiveness of Indonesian health capacities and coordination for Indonesian Hajj pilgrims to relieve the burden on the KSA healthcare system. Future studies will provide the frameworks for analyzing deaths on an individual level to predict health risks and to formulate health intervention capacities required to reduce the health burden resulting from the Hajj pilgrimage.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Masdalina Pane AU - Fiona Yin Mei Kong AU - Tri Bayu Purnama AU - Kathryn Glass AU - Sholah Imari AU - Gina Samaan AU - Hitoshi Oshitani PY - 2019 DA - 2019/03/27 TI - Indonesian Hajj Cohorts and Mortality in Saudi Arabia from 2004 to 2011 JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 11 EP - 18 VL - 9 IS - 1 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.181231.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.181231.001 ID - Pane2019 ER -