Regional Developmentalism in West Africa: The Case for Commodity-based Industrialization through Regional Cooperation in the Cocoa–Chocolate Sector

- DOI

- 10.2991/jat.k.211130.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Cocoa; development; developmental state; ECOWAS; industrialization; regional integration; West Africa

- Abstract

Regional integration occupies a prominent place in the economic policies of most sub-Saharan African countries. However, despite different waves of initiatives across the African continent, the majority of African regional schemes have not managed to achieve their ambitious goal of promoting sustainable development through trade integration in Africa. In light of this observation and using the West African cocoa–chocolate sector as a case study, we propose the regional developmentalism paradigm as an alternative approach to regionalism in Africa. Regional developmentalism places a particular emphasis on the use of regional and subregional approaches to development. Instead of full-fledged trade liberalization and indiscriminate economic integration, the regional developmentalism paradigm advocates for state-led trade facilitation, regulatory convergence, and capacity-building by adopting policies directed at strategic sectors. We evaluate the potential of the regional developmentalism paradigm to promote economic transformation and commodity-based industrialization against the shortcomings of the current regional integration approach embodied in the institutional framework of the Economic Community of West African States.

- Copyright

- © 2021 African Export-Import Bank. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the neoliberal paradigm, regional economic integration should strengthen a region’s commercial interests and foster trade diversification and creation. Trade integration, in particular, involves the removal of tariff and nontariff barriers to trade and is expected to promote the free movement of goods, services, and factors of production across regional borders, thereby accelerating countries’ economic growth and development (Lindberg and Scheingold, 1971). Given its expected benefits, regional integration has been a key policy initiative across the African continent. This is evident in recent efforts to advance regional integration through the signing of the Agreement to establish an African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which aimed to create a continental market for goods and services, beginning March 2018.1 However, despite multiple waves of regional economic integration initiatives over the years, the majority of African regional schemes have not achieved the ambitious goal of economic growth via trade creation, nor have regions become more economically integrated.

Existing literature has pinned the failure of African regional schemes to deliver the intended results to design flaws. More specifically, it is argued that the European Union (EU)-inspired model of economic integration, which most schemes have adopted, is unlikely to be adapted to the specific needs and circumstances of the participating economies. Therefore, it is unable to produce the intended results (Draper, 2010). Under the EU-inspired model, regional integration is achieved through three stages in linear succession: (1) preferential and free trade areas in which participating countries scale down or completely abolish tariffs and other quantitative restrictions on regional trade; (2) a customs union that includes both the abolition of tariffs among participating countries and the adoption of a common external trade policy; and (3) a common market that involves the abolition of all barriers to trade and the free movement of factors of production (labor and capital); for further details, see Balassa (1962) and Kyambalesa and Houngnikpo (2006). More advanced forms can also include an economic union, adopting common economic policies, or a monetary union, with the adoption of a common currency (Balassa, 1962; Kyambalesa and Houngnikpo, 2006).2

Trade creation and integration are expected to occur as countries gain access to larger markets. As cross-border trade provides new markets for exports and cheaper imports, consumer surplus is thought to increase, and production gains are made (Pelkmans, 1986). However, full-fledged trade liberalization and free movement of goods and services are unlikely to be advantageous for most African economies. Their exports are not diversified and predominantly of the low value-added type; see UNECA (1990, p. 19) and UNCTAD (2000, 2002).3 A vast majority of African economies depend on the export of primary commodities and imports of manufactured goods, leading to deteriorating terms of trade. Industrialization, where it has occurred, has been slow. The process is hampered by competition from large Multinational Companies (MNCs), which, equipped with better resources and more attractive products, increasingly access domestic markets. This situation has adversely affected African infant industries, which are often unable to cope with the foreign competition; see Khor (2008) and UNECA (1989). Hence, rather than promoting structural transformation and economic growth, trade liberalization has often increased the regions’ dependence on primary commodity exports, as countries have been unable to promote the growth of their domestic industries.

Consequently, the reduction of trade barriers has failed to promote sustained economic growth in the past, and primary commodity-exporting countries continue to grapple with declining terms of trade and notoriously volatile commodity prices, making effective management of their macroeconomy challenging (Paul, 2003). This reality has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has further exposed Africa’s overreliance on its commodity trade with the rest of the world, raising fears of catastrophic consequences for most African economies (Tröster and Küblböck, 2020; Perry, 2020; Asante-Poku and van Huellen, 2021).

By acknowledging the argument of design flaws in existing regional integration schemes, this paper further argues that the concept of regional integration is inappropriately framed to achieve the objectives associated with it in the context of most African economies. Our contribution is twofold. First, we demonstrate that the perceived automatism between the abolition of tariffs and regional integration is illusionary. We establish the de jure/de facto fallacy and highlight the need for a political economy approach to understanding why an effective regional integration has not occurred in many African schemes. Second, based on our analysis, we propose an alternative concept to regional integration that is more suitable for economies in which the need for structural transformation is prevalent and comparative advantages need to be created through strategic regional governance.

Our alternative approach is based on the concept of regional developmentalism.4 The regional developmentalism approach is inspired by the new developmental state paradigm and argues for a strong emphasis on socio-economic development as the justification for the existence of regional trade arrangements and regional communities. Instead of full-fledged trade liberalization and indiscriminate economic integration, the regional developmentalism paradigm advocates for trade facilitation and inward investments through incentive measures and productive capacity development to reverse the adverse effects of the international economic order on low- and middle-income countries. According to this approach, regional integration schemes that do not achieve these goals should be either dissolved or transformed to prevent them from becoming impediments to the participating countries’ economies.5 Regional developmentalism argues for the adoption of regional and subregional approaches to development, as well as for a set of new policies that emphasize dynamic economic and corporate governance. It takes into account the domestic and regional context and considers the global political economy context within which regions operate and the constraints therein to design effective policies that achieve economic transformation. This approach is recommended to provide for a new and more suitable conceptual paradigm to spur sustainable development across the African continent; see, also, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Framework Document, NEPAD (2001, art. 27), Kouam (2008), and Aka (2012).

In this context, sectoral integration is presented as a viable first step before, or even instead of, full-fledged trade liberalization. Sectoral integration could consider the particular circumstances of the countries participating in regional schemes by targeting key economic sectors that are more likely to help promote industrialization, export diversification, and sustained economic growth through spillovers and the creation of regional value chains. This strategy will likely allow countries to proceed to a gradual liberalization if desired while taking time to strengthen their infant industries’ competitiveness.

The spirit of this approach is already embraced by recent initiatives launched within the African Union, including the Action Plan for Boosting Intra-African Trade Initiative and the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa, which—beyond a simple promotion of cross-border trade and the increase in regional exchanges—emphasizes measures designed to strengthen the productive capacity of African states.6 Similarly, in 2010, the West African Common Industrial Policy (WACIP) was adopted by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to boost the region’s industrialization through regional infrastructure development and the promotion of value-added transformation of raw materials.

The analysis conducted in this paper focuses on ECOWAS, which has adopted an EU-inspired linear approach to regional economic integration. Regulatory and institutional frameworks (de jure integration) have been improved over the years to advance the integration process and establish an economic union. ECOWAS also provides the example of an African Regional Economic Community in which efforts toward an effective formal regional economic integration (de facto integration) have been relatively slow. We illustrate the de jure/de facto fallacy of the regional integration approach, using the example of the cocoa–chocolate sector, which is considered one of the region’s strategic sectors. The sector case study is then used to explore the feasibility and potential of the regional developmentalism approach. In light of the findings of our analysis, the paper first reiterates the argument that the current paradigm of economic integration followed by the region is not appropriate for the needs of the participating countries. Secondly, it outlines how the concept of regional developmentalism could present a viable alternative.

The paper is divided into five sections. Following this introduction, the second section consists of an overview of the progress made by ECOWAS, since its establishment, in developing its regulatory and institutional frameworks (de jure integration). The third section highlights the de jure/de facto fallacy, using the example of the West African cocoa–chocolate sector, and analyzes the causes and consequences of this fallacy. The fourth section makes a case for regional developmentalism to tackle the causes identified in the third section. Based on our analysis, the concluding remarks in the fifth section summarize the arguments developed throughout the paper and reflect on the potential benefits that sectoral integration could bring to the region.

2. de jure INTEGRATION: THE ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF WEST AFRICAN STATES

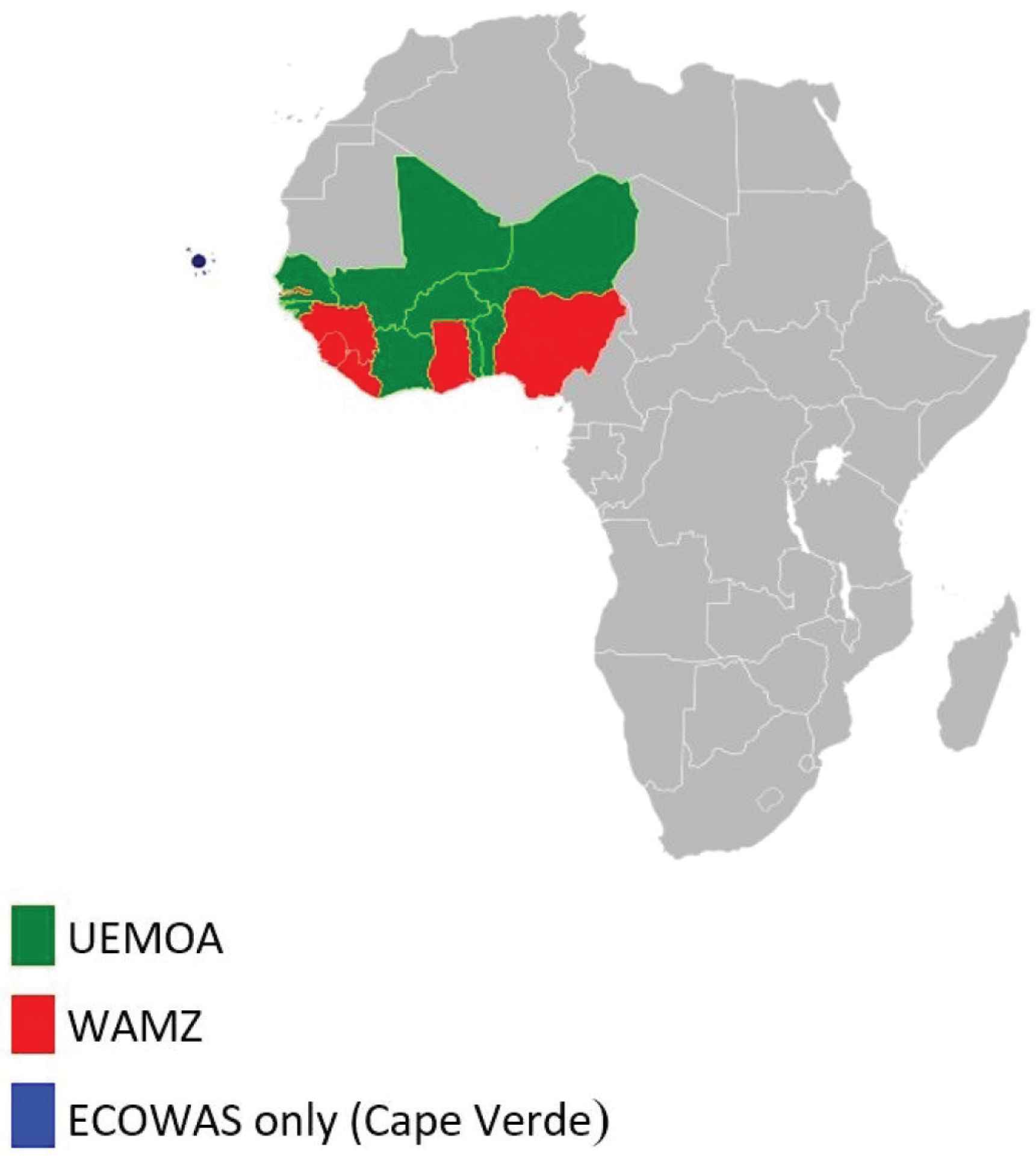

Economic Community of West African States was founded in 1975 as an economic community to promote integration across the West African region. It consists of 15 West African countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.7 ECOWAS countries, apart from Cape Verde, are split into two currency and customs unions: the Union Economique et Monétaire Ouest Africaine (UEMOA) comprises eight ECOWAS Member States (shown in green in Figure 1): Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, and Guinea-Bissau, which share the CFA Franc8 as a common currency. The declared aim of UEMOA is to create a common market and adopt harmonized fiscal policies. Furthermore, ECOWAS and UEMOA have developed a common plan on trade liberalization that includes common rules of origin. The West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ) comprises six ECOWAS countries (shown in red in Figure 1): The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, with the declared aim of introducing a common currency, Eco. In contrast to UEMOA, WAMZ is not a customs union.

Economic Community of West African States Member States and their membership in the Union Economique et Monétaire Ouest Africaine (UEMOA) and the West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ).

Economic Community of West African States was established with the ultimate goal of fostering economic and social development among its Member States. This goal was to be achieved through an “effective cooperation largely through a determined and concerted policy of self-reliance.”9 During the first phase, the integration process focused primarily on several key sectors, including industry, telecommunications, energy, agriculture, natural resources, commerce, monetary and financial issues, and social and cultural matters. This initial approach to regionalism was adopted to accommodate the Member States’ concerns over their sovereignty and independence and was expected to promote and develop the region’s local businesses as well as to promote intraregional trade, thus allowing the Member States to increase their self-reliance and reverse a cycle of significant external dependence. The latter was a direct consequence of the institutional framework inherited from colonialism, which was designed to meet the needs of the former colonial powers for raw materials (Geda, 2003).

The provisions of the ECOWAS Treaty constituted the fundamental and primary source of law in the Community. They were intended to be implemented through secondary legislation issued by two leading institutions: the Authority of Heads of States and Government and the Council of Ministers.10 The harmonization of policies was also recognized as a mechanism necessary for the effective functioning of the Community.11 The treaty harmonized policies in key areas to promote regional development, including harmonization of industrial incentives, industrial development plans, and economic policies (ECOWAS, 1975, art. 30). Other areas that were expected to be covered by the harmonization process included the free movements of goods, services, persons, and capital to create a legal environment broadly the same in all Member States to facilitate the implementation of the treaty provisions (Ovrawah, 1994). Further, a Trade Liberalization Scheme was adopted, aimed at total removal of tariffs on all unprocessed goods and handicrafts, as well as progressive elimination of tariffs on all industrial products from 1981 to 1989 (Omorogbe, 1993).

To further the integration process in the region and ensure the Community’s success in achieving its goal, ECOWAS Member States initiated a series of revisions of the Lagos Treaty, which culminated in the adoption of a new treaty in Cotonou, Benin, in July 1993. Through the 1993 ECOWAS Treaty, the Member States recommitted themselves to economic integration by proceeding to the relevant amendments to the 1975 treaty and attempting to set definite timetables for progress to the following stages of the integration process.12 These amendments were aimed inter alia at strengthening the binding nature of the legal instruments of the Community (Authority’s decisions and Council’s regulations) upon the ECOWAS Member States (ECOWAS, 1993, art. 9[4]; art. 12[3]),13 and the improvement of the Community law-making process (ECOWAS, 1993, art. 9[2]; art.12[2]).

In parallel to strengthening the Community’s regulatory framework, the 1993 Treaty provided for the establishment of new institutions that were intended to increase popular participation in the Community decision-making process, thereby ensuring that these decisions truly reflected the aspirations of the people. Although the Authority and the Council remained generally unchanged, the Secretariat was strengthened and a Community Parliament, an Economic and Social Council and a Court of Justice were introduced (ECOWAS, 1993, art. 6). In particular, the Community Court of Justice was given a wider mandate compared to the Tribunal created under the 1975 Treaty, and the Economic and Social Council was designed to convey the needs and concerns of local businesses to the Community. This initiative strengthened the role of the Community Court in the dispute resolution mechanism, helping it to play a more significant role in the integration process of the region by compelling both Member States and the Community institutions to apply the Treaty provisions in a uniform manner.

The last revision of the ECOWAS legal framework occurred in 2006 with the transformation of the Executive Secretariat into the ECOWAS Commission; see Kufuor (2006) and Gathii (2011). The restructuring provided the Commission with a president, a vice-president, and different commissioners in charge of several departments working on specific areas to be developed through regional cooperation.14 Alongside the transformation of the Commission, a Common External Tariff was adopted by the Authority of Heads of State and Government to ensure the transformation of the Community into a customs union.

To address the region’s continuing dependence on primary commodity exports, ECOWAS adopted two regional legal instruments: the ECOWAS Agricultural Policy (ECOWAP) in 2005 and the WACIP in 2010. ECOWAP aims to apply the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Programme, developed through NEPAD,15 and provides for a Regional Agricultural Investment Plan (RAIP). The RAIP provides general principles to be applied in each Member State through various National Agricultural Investment Plans (ECOWAS, 2005), including food security, fair remuneration of farmers and agricultural wage labor, expansion of trade and value addition, and a common regulatory framework (ECOWAS, 2008). WACIP, on the other hand, is aimed at accelerating the industrialization of the region through local processing of raw materials and the development of regional infrastructure (ECOWAS, 2010, p. 2).

Although the intentions behind the adoption of ECOWAP and WACIP are aligned with the spirit of the regional developmentalism paradigm, these legal instruments lack efficacy in their current form. While efforts for the Member States’ planned interventions under ECOWAP to materialize have been slow and undermined by multiple financial constraints (Crola, 2015), WACIP has not provided an adequate mechanism for applying its policies at the national level. Moreover, WACIP does not provide for appropriate incentives aimed at reversing the current production structure (OSIWA, 2015).

In light of the account of the institutional and regulatory evolution of ECOWAS, we next move to analyze the shortcomings of the existing regional integration approach, using the example of the West African cocoa–chocolate sector. We first identify the absence of regional integration despite the sector’s strategic importance and then demonstrate the benefits of an alternative conceptual approach and corresponding regulatory strategy. The regulatory strategy is specifically designed to promote sectoral integration and commodity-based industrialization and achieve regional development through structural transformation.

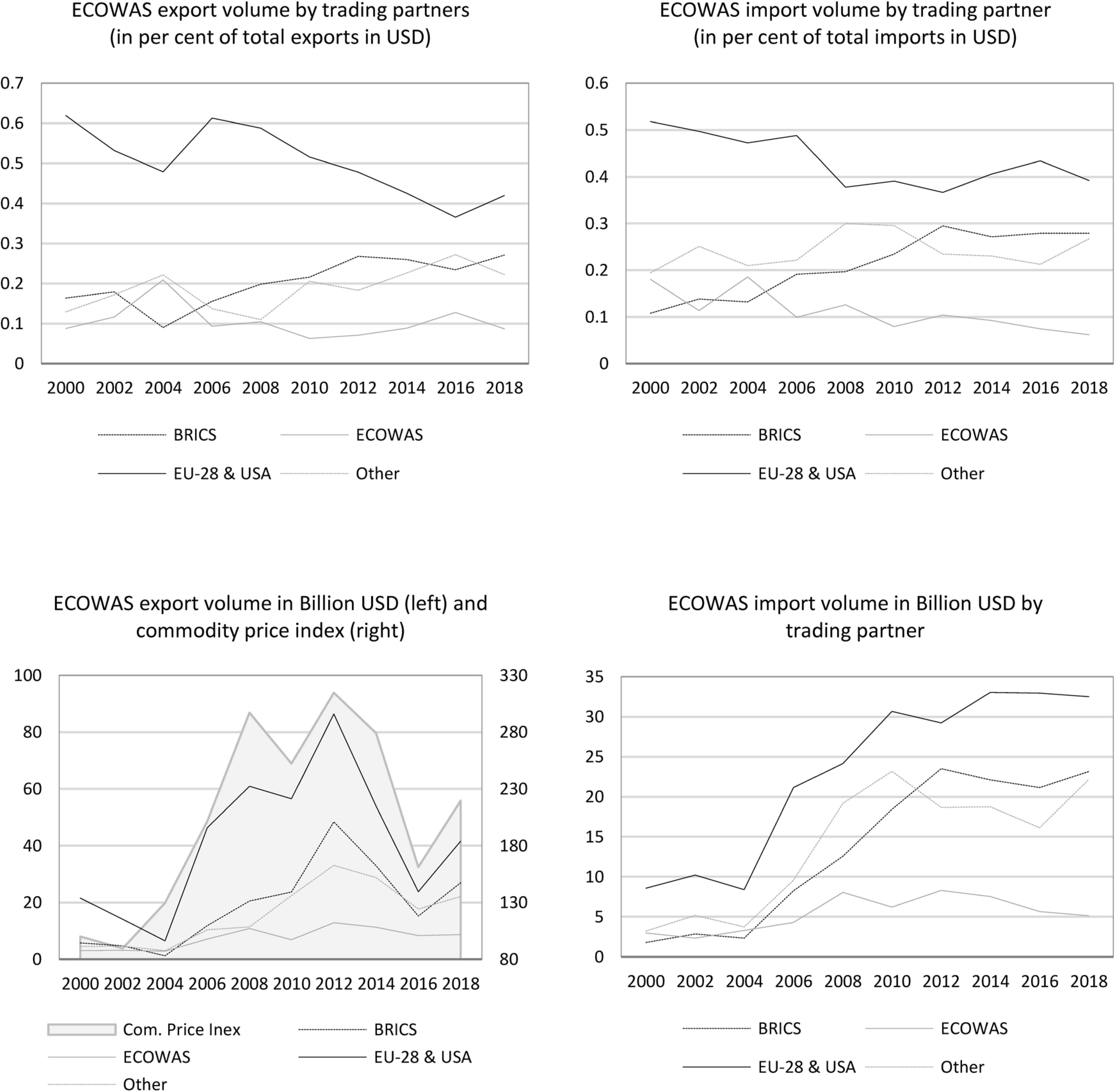

3. de jure/de facto FALLACY

Despite the gradual improvement of its regulatory and institutional frameworks (de jure integration), deeper economic integration within the ECOWAS region has not materialized; see Figure 2. Trade within the region has actually become relatively less important since the establishment of the Free Trade Area in 2000; see, also, ECOWAS (2007) and UNECA (2013b). Although trade volumes grew steadily, the growth in intraregional trade fails to match the rise in exports and imports to and from the EU, the United States, and increasingly, the so-called BRICS economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Tendencies toward trade diversification into higher value-added segments of supply chains are also largely absent, and the region continues to be heavily dependent on primary commodity exports.16 The co-movement of export income painfully demonstrates this with commodity prices while expenditures on imports are largely unaffected by commodity price cycles.17 From the bottom half of Figure 2, it is easy to see how the commodity price slumps of 2016 and 2018 had devastating consequences for the balance of payment position of the ECOWAS region. The region’s continuous reliance on primary commodity exports hampers its efforts toward economic transformation, production diversification, and sustainable economic development (ECOWAS, 2007).

ECOWAS trading partners, percent of annual trade volume in US dollars and annual trade volume in billion US dollars. Source: Comtrade for trade volume; UNCTAD for commodity price index (2015 = 100, all groups).

Part of the lack of economic integration is explained by the fact that most ECOWAS Member States have not yet removed tariff and nontariff barriers to intraregional trade, and thereby, implement a fully functioning customs union (ITC, 2016; UNCTAD, 2018). However, we argue that the observed failure to remove tariff and nontariff barriers and the lack of progress toward increasing regional economic integration is no unintended consequence of slowly adjusting institutional structures, but rather a direct result of the imposition of a misguided paradigm of regional integration. It is against this observed failure of the current paradigm that we highlight the need to adopt an alternative conceptual approach and corresponding regulatory strategy, both specifically designed to promote sectoral integration and commodity-based industrialization and, thus, a more effective regional development facilitated by economic structural transformation.

Taking the West African cocoa–chocolate sector as a case study, we outline the failure of the existing regional integration paradigm to effectively address key bottlenecks that prevent large-scale upgrading into higher value addition and commodity-based industrialization via regional markets. The cocoa–chocolate sector has been identified as a priority industry under WACIP for developing regional industrial plans to raise local processing before export (Traore, 2016).

3.1. The West African Cocoa–Chocolate Sector

As with many agri-food chains, the global cocoa–chocolate chain is shaped by a high concentration of buyer power in the hands of a few MNCs (Gereffi, 1994; Cramer, 1999; Gibbon, 2001; Talbot, 2009). This makes it difficult for newcomers who lack the necessary infrastructure, skills, and size to enter. Two lead segments dominate the global cocoa–chocolate supply chain: grinders who process cocoa beans into intermediate products and branders who manufacture consumable end products and merchandise them (Fold, 2001, 2002). Large supermarket chains have been suggested as an additional lead segment, as they increasingly appropriate a share in value addition by supporting their own brands (Fold, 2008; Fold and Larsen, 2011; UNECA, 2013a). These lead segments are highly concentrated, with a handful of MNCs holding more than 50% of the global market share (TCC, 2010; Gilbert, 2008). In addition to the market power of incumbent MNCs, national and international standards for cocoa beans and cocoa-containing foodstuff are highly complex.18 For many countries, tariffs increase progressively with the degree of cocoa processing, posing an effective barrier to entry.

In this context, it has repeatedly been argued that the most promising route for new entrants into a global value chain is via regional markets (UNECA, 2013a; Nissanke, 2019; Lee et al., 2017). Regional markets can provide necessary linkages and technological spillovers for the infant industries to develop, whereby local firms can build up capabilities in regional markets that are less demanding in terms of standards and competition (Humphrey and Schmitz, 2004). This rationale was at the heart of the revisions of the ECOWAS Treaty in 1993 and 2006, which firmly committed to promoting value addition at the origin. In addition, the latest COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated the fragility of globally dispersed supply networks and reinvigorated interest in regional networks. However, despite West Africa being the single largest region to contribute to world cocoa bean supply, only 2% of the $100 billion cocoa industry is generated in the region, and cocoa beans are largely exported with no or little processing for value addition (Dogbevi, 2019).

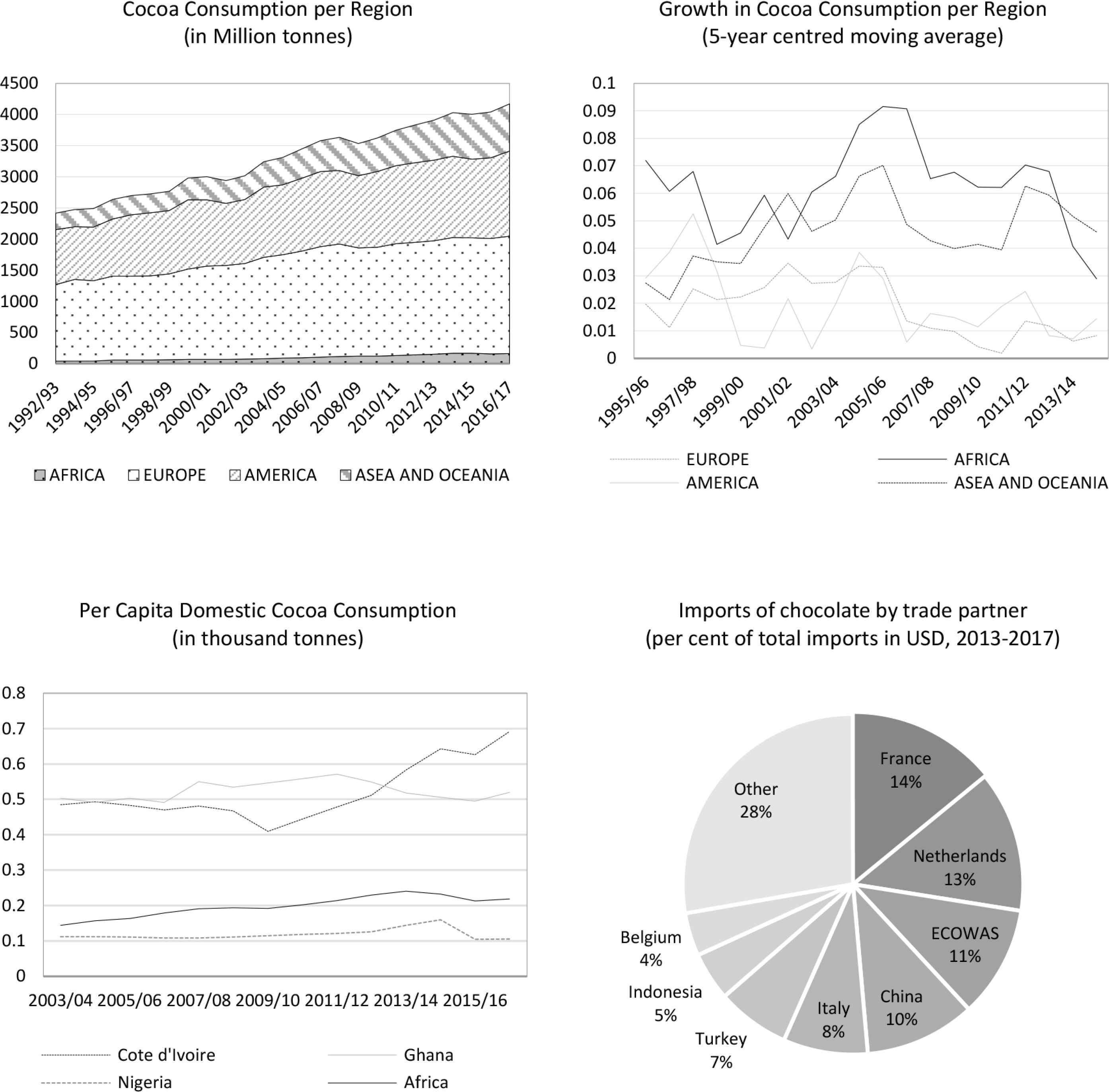

Paradoxically, West Africa and the African continent, in general, are among the fastest-growing markets for consumer chocolate and cocoa-containing foodstuff; the rising demand is satisfied in great part through imports from outside the region (89% of chocolate imports originate from outside the region); see Figure 3. Europe and the Americas (including the United States) remain the largest cocoa-consuming regions. However, growth rates have been low, hovering around 1% annual growth since the global financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession of 2007–08.

Comparison of cocoa consumption by world regions and imports by trade partners, including ECOWAS, of chocolate and other food preparations containing cocoa. Source: ICCO, Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics. UN Comtrade Database.

Over the same time period, growth rates in Africa reached 7% and only declined with the collapse of commodity prices in 2016. The two major cocoa producers, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, have the highest per capita cocoa consumption, while per capita consumption in Nigeria, the largest of the ECOWAS economies, is below the African average despite its proximity to the cocoa-producing centers and being a cocoa producer itself. Evidently, from the growth figures, chocolate and cocoa-containing foodstuff are luxury food items. Demand is strongly correlated with income, and hence, sensitive to economic recession. Although the African chocolate market is still small compared to other world regions, the high growth rates experienced over the last decade, driven by a rising middle class, might turn the region into an attractive investment destination for the confectionery industry.

Value addition in the cocoa–chocolate sector is achieved through grinding. Grinding is the process in which the cell structure of the cocoa nibs (inner bean part after roasting) is broken so that the cocoa butter is released. At this processing stage, one obtains cocoa liquor. The liquor can be pressed to obtain cocoa butter and cocoa cake in equal shares in a second stage. Cocoa butter is an essential ingredient in chocolate, while powder, derived from the cocoa cake, is used for drinking chocolate, cookies, and other confectionery products. Value addition at origin, through grinding, has increased considerably in the region, predominantly through the addition of processing capacity in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. As a result, the African continent increased its share by more than 8% points between 2000 and 2016. However, despite the capacity increase, the continent still has the lowest local processing capacity relative to its bean production. The export of raw beans remains by far the dominant driver of export earnings; see Table 1.

| Cocoa bean productiona | Grinding of cocoa beansa | % share of world production | % share of world grinding | % share of grinding in national production | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2016 | 2000 | 2016 | 2000 | 2016 | 2000 | 2016 | 2000 | 2016 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1403.60 | 2019.60 | 235.00 | 577.00 | 45.62 | 42.62 | 7.94 | 13.13 | 16.74 | 28.57 |

| Ghana | 436.90 | 970.00 | 70.00 | 250.40 | 14.20 | 20.47 | 2.37 | 5.70 | 16.02 | 25.81 |

| Nigeria | 165.00 | 245.00 | 22.00 | 30.00 | 5.36 | 5.17 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 13.33 | 12.24 |

| Europe | – | – | 1335.30 | 1627.50 | – | – | 45.14 | 37.02 | – | – |

| United States | – | – | 447.60 | 390.00 | – | – | 15.13 | 8.87 | – | – |

| Africa | 2155.60 | 3622.90 | 367.50 | 900.50 | 70.06 | 76.45 | 12.42 | 20.49 | 17.05 | 24.86 |

| Americasb | 388.90 | 759.20 | 404.00 | 489.60 | 12.64 | 16.02 | 13.66 | 11.14 | 103.88 | 64.49 |

| Asia & Oceania | 532.50 | 356.70 | 404.10 | 988.00 | 17.31 | 7.53 | 13.66 | 22.48 | 75.89 | 276.98 |

| World | 3077.00 | 4738.80 | 2958.40 | 4395.70 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

In thousand tonnes; figures for 2016 are 2016–17 ICCO estimates.

Without the United States. Source: ICCO, Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics.

Cocoa bean production and grinding per West African country and region

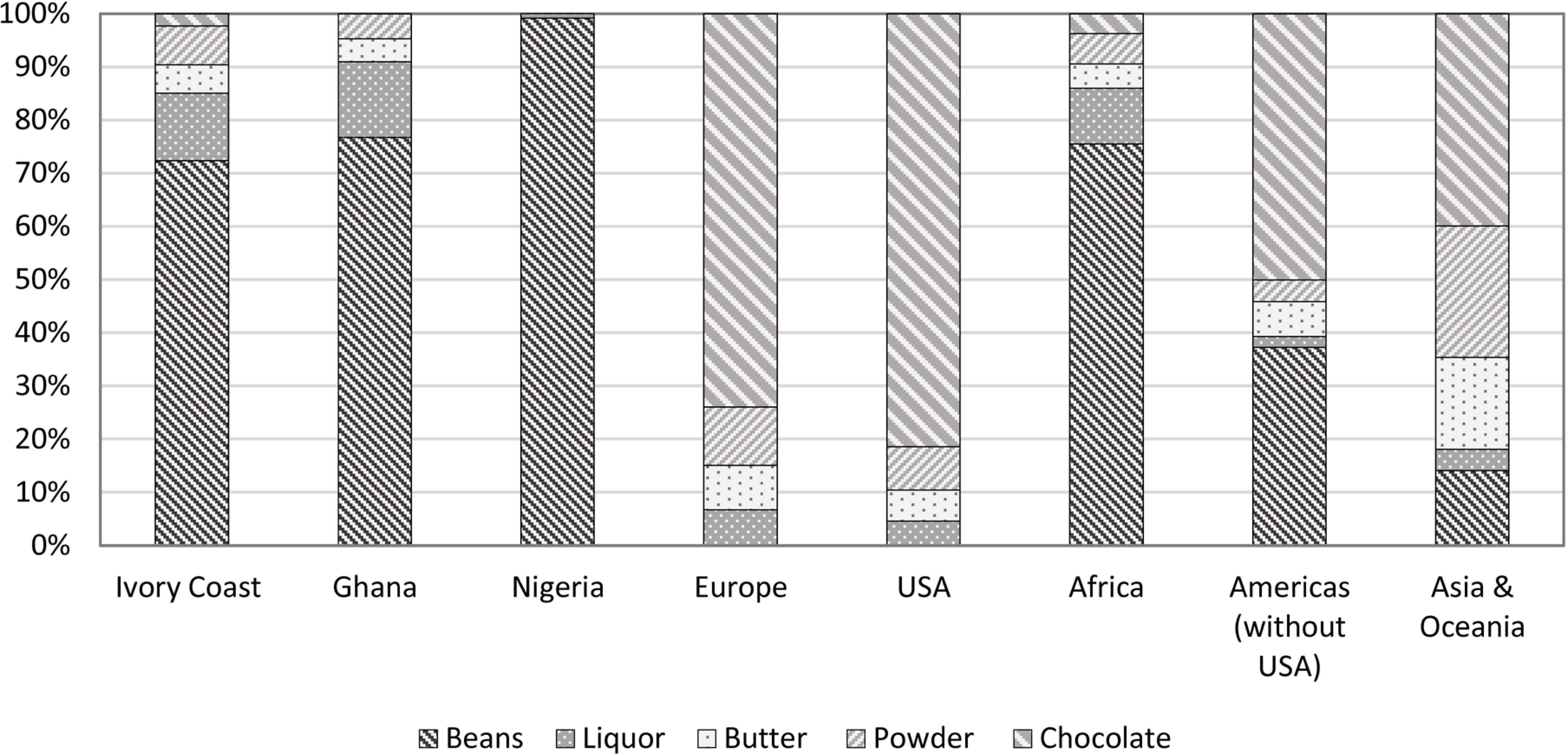

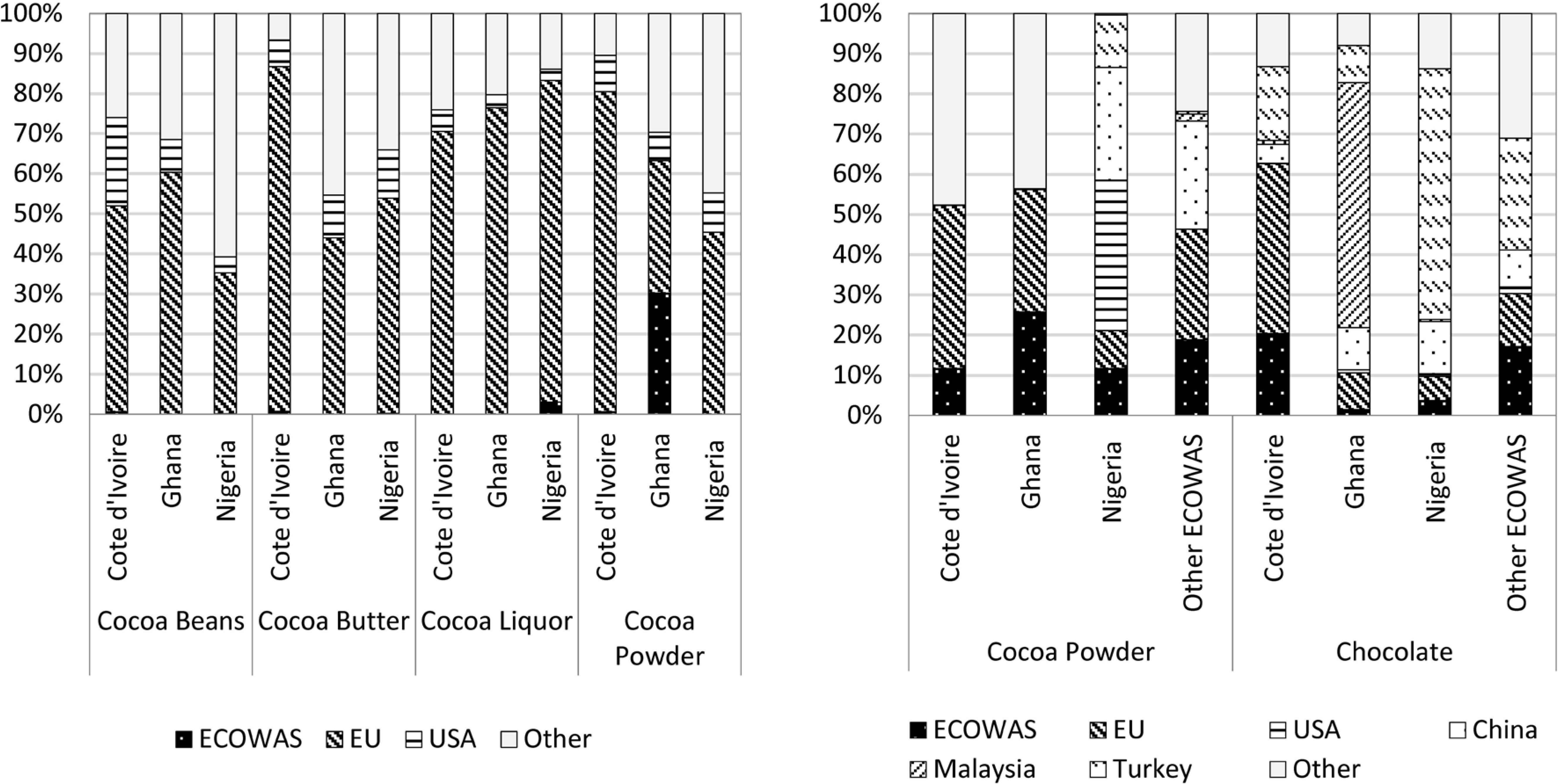

Two patterns emerge when looking more closely into the level of value addition achieved at the origin. First, most processing is at the lower level of value addition (Figure 4), and second, these lower-level, value-added intermediate products are exported predominantly to Europe, while trade within the region in these product categories remains low (Figure 5). Most of the processed cocoa for export is of the liquor type, from the first stage of processing. Only Côte d’Ivoire exports the high value-added segment of consumer chocolate, which is shipped almost exclusively to France. This pattern reflects Côte d’Ivoire’s strong remaining ties with its former colonial ruler. Cémoi, a French chocolate manufacturer, is the sole chocolate producer at the origin. Some of the chocolate is sold domestically through the French retail giant Carrefour, which has recently established a presence in Côte d’Ivoire, while the remaining chocolate is exported to the parent company in France (Cahuzac, 2016). Ghana produces consumer chocolate, too, but production is in the hands of domestically owned companies and (official) export volumes were too small in 2016–17 to show in Figure 4.

Value addition in exports for 2016–17. Note: Percentage estimated from tonnes of exports. This underestimates some of the value addition that is derived from the domestic market. Source: ICCO, Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, various volumes.

Percentage share of trading partners in total exports (left) and imports (right). Notes: Shares estimated from total trade between 2010 and 2015 in tonnes. Categories with less than 200,000 tonnes of trading, combined over the 5-year period, have been excluded. Source: UN Comtrade.

While exports to Europe dominate trading in the lower value-added segments, export and import partners in the higher value-added cocoa powder and chocolate segment are more diverse, with some volume attributed to intraregional trade. Figure 5 depicts trade volume over a 5-year period to overcome the problem of erratic data on intraregional trade. According to Figure 5, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are regional suppliers of cocoa powder, and Ghana is a regional supplier of consumer chocolate. Despite low and volatile trading volumes, almost 20% of Côte d’Ivoire’s chocolate imports between 2010 and 2015 originate from Ghana, and 15% and 25% of Nigeria’s and Ghana’s cocoa powder imports, respectively, originate from Côte d’Ivoire. Senegal re-exports chocolate, imported from Turkey, to its neighboring countries within ECOWAS. Albeit small in scale, regional trade contributes significantly to domestic consumption of cocoa and cocoa-containing foodstuff, supporting the hypothesis that regional markets can promote functional upgrading into higher value-added segments of the cocoa–chocolate chain.19

One should note that Figure 5 does not account for smuggling of cocoa beans across borders between Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Both countries have different price-setting mechanisms that result in potentially huge arbitrage opportunities. Up to 100,000 tonnes, amounting to about 10% of the total annual harvest per country, can change borders in a single crop year. The two countries have recently started coordinating farmgate prices more closely to combat this problem; the coordination was made possible by introducing the Conseil du Café–Cacao in Côte d’Ivoire in 2011, reversing decades of liberalization in the sector (Bymolt et al., 2018). In the most recent act of collaboration, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire joined forces in 2019, demanding a minimum price of $2600 per tonne for the 2020–21 cocoa season to ensure a living income for farmers (Reuters, 2019). However, albeit initially successful, the initiative has been threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic-induced commodity crisis (Asante-Poku and van Huellen, 2021).

3.2. Anatomy of a Failed Regional Integration Paradigm

Despite the potential of a regional market to promote value addition at origin, value addition in the West African cocoa–chocolate sector remains low. Where it occurs in a larger volume (e.g., the chocolate production in Côte d’Ivoire), it seems disconnected from the opportunities regional markets have to offer. These observations outlined in the previous section raise the question of what the hindering factors to value addition through regional markets are. Three factors that might explain the current situation include: (1) the governance structure of the global cocoa–chocolate value chain with lead firms that prevent newcomers from entering traditional consumer markers, claiming new and fast-growing markets for themselves; (2) the absence of a sector-specific, regional industrial plan that considers the interest of all ECOWAS member states, as well as common and idiosyncratic constraints; and (3) the region’s heavy reliance on primary commodity exports for foreign reserve earnings for macroeconomic management.

With the exception of Cémoi in Côte d’Ivoire, which sells its products exclusively via the French supermarket chain Carrefour, the development of a domestic or regional cocoa–chocolate industry has been carried out by domestically owned processors and manufacturers, which operate, with few exceptions, on a smaller scale than their MNC counterparts. The partly state-owned Ghanaian Cocoa Processing Company has long been producing consumer chocolate under the Goldentree brand for the domestic market and recently increased its product portfolio, as well as volume of production. In 2017, Niche entered the Ghanaian market for consumer chocolate. While its main business is focused on semi-processed cocoa for export, some of the cocoa is processed into chocolate for the domestic and regional market. Some small-scale artisan chocolate producers have also recently emerged, such as Instant Chocolat in Côte d’Ivoire, 57 Chocolate and Midunu Chocolates in Ghana, and LoshesChocolate in Nigeria. These observations lead us to the conclusion that functional upgrading through regional markets by domestic companies is possible.

However, despite these existing capabilities in the production of consumer chocolate, production remains small scale and unable to satisfy even domestic demand, as evident from Figure 5. This is despite the sector’s potential for expansion regionally as well as overseas. For instance, South Asia and Southeast Asia are potential markets, given the ability of some of the regionally produced chocolate to withstand relatively high temperatures. This makes it possible to be sold by street vendors—a competitive advantage for many Asian and African markets.20 Indeed, supply-side bottlenecks—such as the lack of key input factors like sugar, unreliable electricity provision, low access to roads and high transport costs, and an underdeveloped banking system—make consumer chocolate produced in the region comparatively expensive. However, the main hindrances to expanding the regional cocoa–chocolate sector are unrelated to the oft-cited supply-side bottlenecks. Instead, they are a direct consequence of inequalities in global economic power structures, not regional market imperfections.

A sizable share of the addition to West Africa’s cocoa processing capacity over the last decade has been driven by Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Governments across the region have made efforts to provide incentives for FDI inflow, for instance, by introducing economic free zones that provide tax exemptions for export-oriented businesses and discounts on domestically sourced cocoa beans (e.g., in Ghana),21 or by the issuance of export expansion grants (e.g., in Nigeria) (UNECA, 2013a). The production of these foreign-owned processing plants is mainly of the low value-added type (with the exception of Cémoi in Côte d’Ivoire) and exclusively reserved for exports to parent companies for further processing. The fact that incentive structures are tied to value addition for exports (and not to the domestic or regional market) is an immediate response to the region’s disadvantaged position in the international monetary system and globalized finance that cements its high dependence on “hard” currency for foreign reserve accumulation (Nissanke, 2019; van Huellen and Abubakar, 2021).

The ECOWAS countries maintain different exchange rate regimes, and regardless of the particular regime, large amounts of foreign reserves are required for macroeconomic management. The currency of the WAEMU, the CFA franc (now Eco), is pegged against the Euro. Until recently, to maintain the fixed exchange rate, the Central Bank of the West African States (BCEAO) deposited a minimum of 50% of its foreign reserves with the French Treasury. France, in turn, guaranteed full convertibility between the CFA franc and the Euro. The arrangement was a relic of the region’s colonial past and has been repeatedly criticized for constraining monetary policy and imposing high opportunity costs by requiring the deposit of foreign reserves with the French Treasury. Also, with the BRICS economies growing in importance as trading partners, a peg against a single currency is increasingly inadequate. In recent years, sufficient reserves to maintain the peg could only be reached by issuance of Eurobonds by Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, adding to the region’s foreign-denominated public debt level. Other currencies, for example, the Ghanaian Cedi or the Nigerian Naira, do not follow a peg, resulting in these being highly susceptible to commodity price fluctuations. For example, the recent collapse of oil prices has weakened the Naira and Cedi considerably, and central banks have been required to intervene, with the use of foreign reserves, in order to defend the currency if necessary.

Cocoa-based exports contributed about 20% and 40% of Ghana’s and Côte d’Ivoire’s export earnings, respectively, in 2015–16. Policies, such as establishing special economic zones or providing export expansion grants, are aimed at value addition for exports outside the region, not for the domestic or regional market. The main intention of these policies is the acquisition of foreign exchange. For instance, Niche in Ghana acts mainly as a processing company for intermediate products to satisfy the 70% of production for an export threshold to qualify for tax reductions. Domestically owned processing companies are required, like their foreign-owned counterparts, to purchase cocoa beans with US dollars, ensuring foreign reserve earnings are made on the full harvest. As domestic companies lack access to cheap US dollar funding, it is not surprising that most processing companies, which work on a high volume, are foreign-owned (van Huellen and Abubakar, 2021). Foreign-owned companies, mainly MNCs, have not yet moved into exploiting the fast-growing consumer markets of West Africa. The MNCs’ business model relies firmly on retailers to reach consumer markets. However, as retail giants expand into the West African consumer markets, more MNCs may engage in domestic chocolate production.22 It is this combination of the needs of regional governments for foreign reserves and the disinterest (for now) of MNCs for higher value addition at origin that results in West African cocoa-producing countries remaining locked into the lower value-added segment. Full-fledged regional trade liberalization does not challenge either of these two conditions.

Within the ECOWAS region, Nigeria is the most important consumer market in which to tap. As the region’s largest and most populated economy, Nigeria could provide a fertile ground for a regional cocoa–chocolate sector to develop, overcoming the limitation of relatively small domestic markets (Nissanke, 2019). However, Nigeria is also a cocoa-producing nation; see Table 1. Although the volume of production is considerably lower than for Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria has intentions to revive its cocoa sector as well as to expand its cocoa processing capacity for the domestic consumer market, and Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are viewed as competitors rather than allies in the establishment of a regional cocoa–chocolate sector (PwC, 2017). Considering that the major share of imported chocolate originates from outside the region, according to Figure 5, this concern is unfounded.

A sectoral approach to regional integration must therefore consider the region’s position within the global economy and global finance, as well as the interests of incumbent market leaders and the interests of all Member States within the region. This includes acknowledging that removing tariff or nontariff barriers will do little to address existing challenges. Quite to the contrary, it could promote the import of consumer chocolate from outside the region, as evidenced from chocolate imported from Turkey, Malaysia, and Europe into the ECOWAS region; see Figure 5. The establishment of a regional currency, the Eco, could potentially address the region’s dependence on foreign revere earnings, as discussed in the next section. At the same time, the interests of individual Member States could be aligned by a carefully negotiated and crafted industrial plan.

4. SECTORAL INTEGRATION AND REGIONAL COOPERATION: TOWARD A NEW PARADIGM

de facto regional integration in the cocoa–chocolate sector is currently limited in West Africa and hampered by remaining tariff and nontariff barriers to trade, partly driven by conflicting interests of the main cocoa-producing countries and fear of competition from neighboring countries. Given the growing influx of consumer chocolate and cocoa-containing foodstuff from outside the region, this concern is misguided, and concerted efforts should be made toward more regional cooperation to build, develop, and strengthen a regional production network. Regulatory instruments under ECOWAS, namely the ECOWAP and WACIP, could potentially facilitate further cooperation, if provided with sufficient resources. An appropriate WACIP, for example, should identify key industrial sectors in a coordinated effort with ECOWAP, such as the cocoa–chocolate sector. This could promote economic growth in the ECOWAS region and ensure that foreign and regional investments are harnessed to promote commodity-based industrialization. However, the ECOWAS institutional set-up is still insufficient and suffers from funding constraints and coordination failures.

These challenges call for a carefully coordinated approach to sectoral integration, which could be best led by the two state-owned marketing boards in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, in collaboration with the Ministries of Finance of the ECOWAS Member States, including Nigeria as another cocoa producer in the region and the ECOWAS Department of Agriculture, Environment and Water Resources (DAEWR). The sectoral approach cannot be limited to cocoa alone but must take a holistic view of the cocoa–chocolate sector and its value chain, including the sourcing of relevant input factors, ranging from fertilizer to sugar, dairy, and packaging, all currently sourced from outside the ECOWAS region. These forward and backward linkages have to be carefully identified, forged, and promoted.23 For sectoral integration to be successful, coordination efforts must involve private sector stakeholders across the value chain.

A holistic sectoral approach that brings together and aligns the interests of different industry and policy stakeholders could potentially address existing bottlenecks, help in sourcing key input factors, and thereby align the interests of the different Member States. In addition to coordination across the value chain, large-scale public investment is required to create positive externalities, overcome existing bottlenecks, and crowd-in private investments at different value chain segments (Nissanke, 2019). For a regional chocolate industry to prosper, the dairy sectors in Niger and Nigeria are promising, while Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria produce sugarcane of relevant volume. The promotion of investments in industries such as dairy, sugar, and packaging, combined with an effective reduction of tariff and nontariff barriers targeting these sectors, would make it possible to develop regional value chains more quickly.

Therefore, a clearly designed and skillfully coordinated industrial policy is essential for the West African cocoa–chocolate sector to expand. A Cocoa Regional Industrial Policy (RIP), which aligns with the proposed paradigm based on regional developmentalism, has already been suggested as an appropriate regulatory solution (Traore, 2016). The region’s growing demand for chocolate and cocoa-containing foods provides a fertile ground for developing a regional industry. Regional capabilities in chocolate production already exist. Once matured, the industry could tap into potential consumer markets overseas and across the continent. The Cocoa RIP can be used to improve the business environment for cocoa–chocolate production, including through a concerted and strategic effort to establish more special economic zones across the region, which would give infant industries the opportunity to develop their competitiveness, while building and strengthening regional value chains. Further steps would be to support increased access to financial and technical resources in the sector across the region and help channel more investment in related sectors.

These initiatives should be combined with measures that protect the region’s infant industries from the rest of the world in the short and medium run. Infant industry protection measures would include tariffs, import quotas, and subsidized government loans. At the same time, protective measures within the region should be reduced to provide a market of sufficient size for inputs and consumption. Low tariffs for processed cocoa and consumer chocolate and cocoa-containing foodstuff are already in place for UEMOA members, benefiting Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa–chocolate sector. These should be expanded to the ECOWAS region. Protective measures could be accommodated under the WTO Enabling Clause, which is designed to benefit regional trade agreements that involve less developed countries, as well as GATT 94, art. XVIII includes special measures for protecting and nurturing infant industries in developing countries; see the discussion on safeguard measures and GATT 94, art. XVIII in Bashi Rudahindwa (2018, p.47). These measures would be temporary, allowing the region to promote full liberalization once higher levels of industrialization and competitiveness have been achieved (Adewale, 2017).

For the Cocoa RIP to be successful, infrastructure investment must be an integral part of its design to address the high demand for transport infrastructure and create or strengthen trade routes across the region to promote physical integration. This is critical to the development of regional value chains. To address the institutional gap within ECOWAS, the Cocoa RIP should be specifically designed to strengthen the capacity of industry support institutions, such as the Regional Agency for Agriculture and Food (RAAF)—the ECOWAP implementation agency under the control of the DAEWR. The RAAF could work more closely with the two state-owned marketing boards in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, their counterparts in other ECOWAS Member States, and regional industry stakeholders, allowing them to foster a more competitive and more interconnected regional market.

Given the region’s dependence on foreign reserve earnings, a regional approach to macroeconomic management must also be part of a holistic sectoral approach. Recent attempts to establish a common regional currency—the Eco—could ease this constraint, depending on the design of the new currency and the institutions supporting it. However, the introduction of a common Eco within ECOWAS, including both UEMOA and WAMZ, seems unlikely in the near future, given heterogeneity in the different economies involved and skepticism among some key players like Nigeria. The recent replacement of the CFA Franc with the Eco is more symbolic than functional, as the Eco of the UEMOA is still pegged to the Euro, and foreign reserves are still required to maintain the peg. In principle, a common currency can ease foreign exchange constraints for input requirements if inputs are sourced within the region. However, a monetary union bears risks, especially if member states are heterogeneous. Since the need for foreign reserve earnings, in part, stems from a reliance on international financial markets to source funding at competitive rates, a deepening of financial markets within the region, and the development of regional banks (which could facilitate large-scale, productive investments at competitive rates) can reduce some of the foreign reserve requirements (Nissanke, 2019).

Therefore, a well-designed Cocoa RIP would be used to promote market opportunities, address challenges (regional and external), and support competitiveness through increased investment, capacity development, and funding. Efforts from individual countries to move into higher value-added segments of the cocoa–chocolate chain would benefit from a regional regulatory framework for the sector, which can tackle various supply-side bottlenecks, coordinate the chain segments, and provide a large enough market for dynamic externalities and spillovers required for a move into the higher value-added segment.

5. CONCLUSION

Regional integration has been a key policy initiative across the African continent, as evidenced by the multiple and growing regional schemes. Yet, most existing schemes have failed to deliver on their objectives of trade creation, trade diversification, and regional economic integration. Acknowledging the conventional argument of design flaws in the institutional arrangements of existing regional schemes to explain these failures, we go further and argue that the concept of regional integration is inappropriately framed to achieve the objectives associated with it in the context of most African economies, which suffer from a primary commodity export dependence and a low level of export diversification. We argue that, in this context, the sole reduction of tariff and nontariff barriers to trade (the prime policy tool for regional integration schemes to fulfill their objectives) is unlikely to result in trade creation and diversification, or industrialization.

We demonstrate this hypothesis by focusing on ECOWAS, which has adopted an EU-inspired linear approach to regional economic integration, in which both regulatory and institutional frameworks (de jure integration) have been improved over the years to advance the integration process and establish an economic union. At the same time, efforts toward an effective formal regional economic integration (de facto integration) have been relatively slow. Taking the West African cocoa–chocolate sector as a case study, we identify three key factors that contribute to the de jure/de facto fallacy of the ECOWAS regional integration schemes: (1) the governance structure of the global cocoa–chocolate value chain, which is dominated by a handful of multinational lead firms; (2) conflicting interests of ECOWAS Member States; and (3) the region’s heavy reliance on primary commodity exports for foreign reserve earnings for macroeconomic management. None of these hindering factors to regional economic integration can be resolved through reduction of barriers to trade.

Based on our analysis, we propose an alternative concept to regional integration that can address the challenges described herein and is more suitable for economies in which the need for structural transformation is prevalent and comparative advantages need to be created through strategic regional governance. Our alternative approach is based on the concept of regional developmentalism, which advocates for gradual rather than full-fledged trade liberalization and the establishment of regional value chains to promote regional development through industrialization, economic transformation, and export diversification. We evaluate the regional developmentalism approach for the West African cocoa–chocolate sector, a promising and strategic sector for the region.

Using the example of the West African cocoa–chocolate sector, we demonstrate the importance of a sectoral approach, which takes a holistic view of the cocoa–chocolate sector, its value chain, and ECOWAS Member States’ private and public stakeholder interests. We propose the adoption of a Cocoa Regional Industrial Policy (RIP), specifically designed to address regional and external challenges and to achieve the development of a competitive, regional cocoa–chocolate value chain through targeted intraregional trade facilitation, temporary infant industry protection, crowding-in of private sector investments at different segments of the value chain, and careful coordination between different private and public sector stakeholders across the value chain. The incentive measures provided in the Cocoa RIP, combined with an effective reduction of tariff and nontariff barriers targeting those key industries within the region, would accelerate the development of regional value chains, and thereby, promote commodity-based industrialization and economic transformation toward a globally competitive cocoa–chocolate sector.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

JBR contributed in study conceptualization. JBR and SvH contributed in writing the manuscript (original draft, review, and editing). SvH contributed in data curating and analysis.

FUNDING

No financial support was provided.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to participants of the Development Studies Association (DSA) Conference in September 2016 at the University of Oxford, and the Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network (PEGNet) Conference on Regional Integration for Africa’s economic transformation at the University of Kigali in September 2016, for useful comments.

Footnotes

AfCFTA was launched at the 10th Extraordinary Session of the Assembly of the African Union, held in Kigali, Rwanda, on March 21, 2018.

The Eurozone, which includes 19 of the 28 members of the European Union, is an example of a more advanced form of regional integration.

It is argued in UNECA (1990) that, although trade liberalization could result in a significant increase of exports, it might not constitute the most appropriate measure to help developing countries diversify their exports and shift their production systems out of primary commodities to promote sustained economic growth. The report argues for trade policies that consider local circumstances and maximize a sustained domestic growth, including policies that may not involve the reduction of trade barriers.

The paradigm of regional developmentalism was developed in Bashi Rudahindwa (2018). It is inspired by discussions in Charles Sherman (2009) and Trubek (2009). This approach differs from the concept of developmental regionalism, in that it places greater emphasis on identifying the harmful effects of the international economic order on developing countries as well as on the various measures to be adopted to overcome them. Developmental regionalism is discussed in UNCTAD (2013) and in Ismail (2020).

An example is the East African Community, which was established in 1967, but dissolved in 1977 because of structural problems, before being re-established in July 2000.

For further details on BIAT and PIDA, see https://au.int/en/ti/biat/about and https://au.int/en/ie/pida.

Although originally a member, Mauritania left ECOWAS in 2000 to join the Arab Maghreb Union, which now consists of Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia.

Franc of the Financial Community of Africa (French: Franc de la Communauté Financière Africaine)

See the Preamble of the 1975 ECOWAS Treaty.

The 1975 ECOWAS Treaty, art. 5(3) provided for the decisions and directions of the Authority of Heads of States and Government, whereas art. 6(3) provided for the ones for the Council of Ministers.

The 1975 ECOWAS Treaty, art. 2(g) provides for “the harmonisation of the economic and industrial policies of the Member States and the elimination of disparities in the level of development of the Member States.”

The 1993 ECOWAS Treaty, art. 3(2) provides for clear stages intended to lead the Community toward the establishment of a common market. Moreover, art. 35 and art. 54 provide for fixed deadlines for the establishment of a customs union (within 10 years from January 1, 1990) and a monetary union 5 years after the customs union.

The legal instruments adopted by the Council were renamed “regulations” in order to distinguish them from the “decisions” made by the Authority.

These departments include Administration and Finance; Agriculture, Environment and Water Resources; Human Development and Gender; Infrastructure; Macro-economic Policy; Political Affairs, Peace and Security; Trade, Customs, Industry and Free Movement.

The CAADP was established by NEPAD in 2003 to promote agricultural development across the continent.

All ECOWAS Member States were listed as commodity export dependent in the UNCTAD (2019) report on the state of commodity dependence. Most ECOWAS Member States’ exports contain more than 80% primary commodities.

The exception here are imports of refined oil from the United Arab Emirates that are accounted for under the “Other” category.

For example, for European countries, the standards are set by the Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006, which sets maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuff.

Similar observations hold for other value-added consumer products consumed in the region for which regional trade is significant (ITC, 2016). Overall, the region remains primarily commodity export dependent, however.

Hershey registered a patent for chocolate that can withstand high temperatures in 2014. Such receipt is crucial to expand into many consumer markets in Asia and Africa, where snacks like chocolate are predominantly sold by street vendors and often in high temperatures.

Since 2000, nine processing companies have been established in Ghana alone, of which six are either foreign owned or joint ventures with foreign companies.

The so-called supermarket revolution has seen traditional retail giants, as well as newcomers, entering consumer markets across the African continent in recent years; see Humphrey (2007); Campbell (2016).

The argument here is aligned with points made by Hauge (2020) and Behuria (2020) who stress the importance of combining the GVC perspective with a developmentalist industrial policy and political economy perspective.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from UN Comtrade [https://comtrade.un.org/], UNCTAD [https://unctadstat.unctad.org/], and the ICCO Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics [https://www.icco.org/].

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Jonathan Bashi Rudahindwa AU - Sophie van Huellen PY - 2021 DA - 2021/12/09 TI - Regional Developmentalism in West Africa: The Case for Commodity-based Industrialization through Regional Cooperation in the Cocoa–Chocolate Sector JO - Journal of African Trade SP - 82 EP - 95 VL - 8 IS - 1 SN - 2214-8523 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jat.k.211130.001 DO - 10.2991/jat.k.211130.001 ID - Rudahindwa2021 ER -