The Re-emergence of a Forgotten Disease: Neurobrucellosis

, Makram Koubaa, Amal Chakroun, Fatma Smaoui, Emna Elleuch, Chakib Marrakchi, Mounir Ben Jemaa

, Makram Koubaa, Amal Chakroun, Fatma Smaoui, Emna Elleuch, Chakib Marrakchi, Mounir Ben Jemaa- DOI

- 10.2991/dsahmj.k.201010.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Brucella; neurobrucellosis; meningitis; magnetic resonance imaging

- Abstract

Brucellosis may present with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations. Neurobrucellosis (NB), an uncommon but a serious complication, may occur at any stage of the disease. We aimed to evaluate the clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic, and evolutionary features of NB. We conducted a retrospective study including all patients hospitalized for neurobrucellosis in the infectious diseases department between 1994 and 2018. The diagnosis was based on the association of neurological symptoms with bacteriological and/or serological confirmation of brucellosis in blood or Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF). There were 16 patients (10 male) with NB. The median (range) age was 35 (24–48) years. The revealing symptoms were fever (n = 15), headache (n = 12), and vomiting (n = 9). CSF analysis showed lymphocytic pleocytosis (n = 9) and a high level of protein (n = 10). Brucella was isolated from the blood and CSF in two and five cases, respectively. All patients had a positive Brucella serological test. Eleven patients received rifampicin, doxycycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The median (range) duration of treatment was 4.5 (3–5.3) months. The disease evolution was favorable in 13 cases. Sequelae were noted in one case. Two patients died. In cases of unusual neurological disorders, NB should be considered, especially in endemic areas. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial in order to avoid serious complications and sequelae.

- Copyright

- © 2020 Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Brucellosis, a relatively common zoonosis worldwide, is endemic in the Mediterranean and Middle East [1]. In endemic countries, it is responsible for a disabling disease and a high morbidity rate [2]. In recent years, the discovery of novel Brucella has considerably expanded the genus (12 recognized species). Four species, Brucella melitensis, Brucella abortus, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis, are the main causes of the disease in humans [3]. Brucellosis is a multisystem disease that might present with myriad clinical manifestations such as fever, fatigue, sweats, and malaise, as well as complications, such as arthritis, endocarditis, and neurological disorders [2]. Neurological manifestations of brucellosis or Neurobrucellosis (NB), the most important complication of the disease [4], occurs in up to 25% of the patients [5]. The most common presentation of NB is meningoencephalitis, which occurs in 50% of the cases [6]. The clinical spectrum of NB includes meningitis, meningoencephalitis, brain abscess, epidural abscess, myelitis, radiculoneuritis, cranial nerve involvement, or demyelinating or vascular disease [7]. Diagnosis is made by evidence of systemic Brucella infection and positive Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) findings, including lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, decreased glucose, and positive serology. Positive CSF culture for Brucella is a less-frequent diagnostic method [5]. The treatment includes more than one antibiotic, such as doxycycline and rifampicin, that crosses the blood–brain barrier and achieves good CSF concentration [8].

In Tunisia, brucellosis is still endemic and represents a public health problem given its upsurge in recent years due to increasing contamination of livestock that escapes vaccination [9]. Recent data about NB in our region are lacking. A better knowledge of this disease may help clinicians to better manage neurological manifestations in brucellosis and to improve its prognosis. In this perspective, we aimed to evaluate the clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic, and evolutionary features of NB.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a retrospective study including all patients hospitalized for NB in the infectious diseases department over a 25-year period, from January 1994 to December 2018.

2.2. Data Collection and Case Definition

The diagnosis was based on evidence of Brucella infection, represented by a Wright’s serum agglutination test >1/80 and/or detection of Brucella spp. in blood or CSF, associated with positive CSF findings among patients presenting with neurological symptoms. Positive CSF findings included lymphocytic pleocytosis (>5 cells/mm3), elevated protein (>0.45 g/L), and decreased glucose level (CSF-to-blood glucose ratio <40%). We collected data from the patients’ medical records. Epidemiological data including age, sex, and occupation were noted. The revealing symptoms, physical examination results, and laboratory investigations (both blood and CSF serological and bacteriological tests) were reported. Radiological results, antibiotics prescribed, treatment duration, and disease evolution were reported.

3. RESULTS

Over a 25-year period, 16 patients had NB among 152 patients with brucellosis treated in our department, representing 10.5% of all cases of brucellosis. There were 10 male patients, and the median (range) age was 35 (24–48) years. Five patients were exposed to the disease at work: four patients were agricultural workers and one was a butcher. Ten patients consumed fresh (unpasteurized) milk and/or byproducts. The most common revealing symptoms were fever (n = 15 cases), headache (n = 12), vomiting (n = 9), and asthenia (n = 7). Patients consulted for blurred vision (n = 3), confusion (n = 3), and hearing loss (n = 2). Physical examination revealed fever (n = 15), meningeal syndrome (n = 7), and cranial nerve involvement (n = 6) (Table 1).

| Patient No. | Age (years) | Sex | Complaints | Neurological findings | Neurobrucellar form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 | M | Fever, asthenia, vomiting, headache, hearing loss | Peripheral facial paralysis, neck stiffness | Meningoencephalitis and cerebellitis |

| 2 | 30 | M | Fever, vomiting, headache | Papilloedema | Meningitis |

| 3 | 12 | M | Fever, vomiting, headache | Convergent strabismus, neck stiffness, papilloedema | Meningitis |

| 4 | 44 | M | Fever, headache | Aphasia, neck stiffness, behavioral disorder | Meningitis |

| 5 | 44 | F | Fever, asthenia, vomiting, headache | Neck stiffness, behavioral disorder | Meningitis |

| 6 | 41 | M | Fever, asthenia, arthralgia, headache, confusion | Peripheral facial paralysis, agitation, neck stiffness | Meningoencephalitis |

| 7 | 28 | M | Vomiting, asthenia, headache, blurred vision | Diplopia, convergent strabismus, aphasia, papilloedema | Meningitis |

| 8 | 50 | M | Fever, arthralgia, myalgia | Motor and sensitive deficit | Radiculitis |

| 9 | 43 | M | Fever, vomiting, headache, blurred vision | – | Meningitis |

| 10 | 30 | M | Fever, asthenia | – | Meningitis |

| 11 | 65 | F | Fever, asthenia, arthralgia, hearing loss, headache, | Bowel and urine incontinence, walking disorder, motor and sensitive disorder | Meningomyeloradiculitis |

| 12 | 18 | F | Fever | Walking disorder | Meningomyeloradiculitis |

| 13 | 26 | F | Fever, vomiting, headache, confusion | Agitation, disorientation, neck stiffness | Meningitis |

| 14 | 17 | F | Fever, vomiting, arthralgia, myalgia, headache, blurred vision | Diplopia, neck stiffness, papilloedema | Meningitis |

| 15 | 24 | F | Fever, vomiting, headache, confusion | Coma, areflexia | Encephalitis |

| 16 | 57 | M | Fever, asthenia | Papilloedema, a present Babinski reflex | Meningitis |

F, female; M, male.

Clinical features of 16 patients with neurobrucellosis at admission

Three patients had leucopoenia (Nos. 8, 13, and 16). Anemia and thrombocytopenia were noted in five (Nos. 1, 2, 8, 11, and 13) and three (Nos. 6, 13, and 16) cases, respectively. Lumbar puncture was performed in all cases, and revealed pleocytosis in 13 cases with a median (range) White Blood Cell (WBC) count of 150 (8–470)/mm3. Three patients had normal CSF WBC count (<5 cells/mm3) (Nos. 8, 13, and 15). Nine patients had lymphocytic pleocytosis. One patient (No. 12) had neutrophil pleocytosis. Among patients with pleocytosis, three had low WBC count in CSF (<20/mm3), in whom we could not identify the type of pleocytosis (Nos. 9, 10, and 16). Ten cases had an elevated median (range) CSF protein level of 1.47 (0.6–14) g/L, and seven cases had a low CSF glucose level. Brucella was isolated from the blood in two cases and from the CSF in five cases. All patients had a positive Brucella serological Rose Bengal test. Wright’s serum agglutination test was positive in 15 cases. One patient had a negative Wright’s serum agglutination test, although Brucella was isolated from CSF culture (No. 6). Wright’s serum agglutination test was performed in CSF in three cases and was positive in one (No. 10) (Table 2).

| Patient No. | WBC (mm3) | Serum Brucella agglutination titer | Blood culture | CSF cell count/mm3(% of Ly), n (%) | CSF protein level (g/L) | Low level of CSF glucose | CSF culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7940 | 1:80 | – | 285 (80) | 1.04 | No | – |

| 2 | 7760 | 1:2560 | + | 110 (98) | 0.84 | Yes | + |

| 3 | 8700 | 1:1280 | – | 336 (72) | 0.15 | Yes | + |

| 4 | 4500 | 1:1280 | + | 70 (95) | 0.6 | No | – |

| 5 | 7600 | 1:320 | – | 410 (78) | 1.9 | Yes | – |

| 6 | 13800 | Negative | – | 370 (75) | 0.75 | Yes | + |

| 7 | 6600 | 1:640 | – | 160 (72) | 3 | Yes | + |

| 8 | 3800 | 1:320 | – | 1 | 0.1 | No | – |

| 9 | 5000 | 1:320 | – | 15 | 0.45 | No | – |

| 10 | 8100 | 1:640 | – | 8 | 0.25 | No | – |

| 11 | 5200 | 1:640 | – | 150 (75) | 9 | Yes | + |

| 12 | 7100 | 1:80 | – | 470 (40) | 14 | Yes | – |

| 13 | 2700 | 1:640 | – | 3 | 2.7 | No | – |

| 14 | 9780 | 1:160 | – | 80 (95) | 0.34 | No | – |

| 15 | 7108 | 1:320 | – | 1 | 0.3 | No | – |

| 16 | 2400 | 1:160 | – | 12 | 0.7 | No | – |

Ly, lymphocytes; WBC, white blood cell; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; %, percentage.

Results of laboratory findings of 16 patients with neurobrucellosis at admission

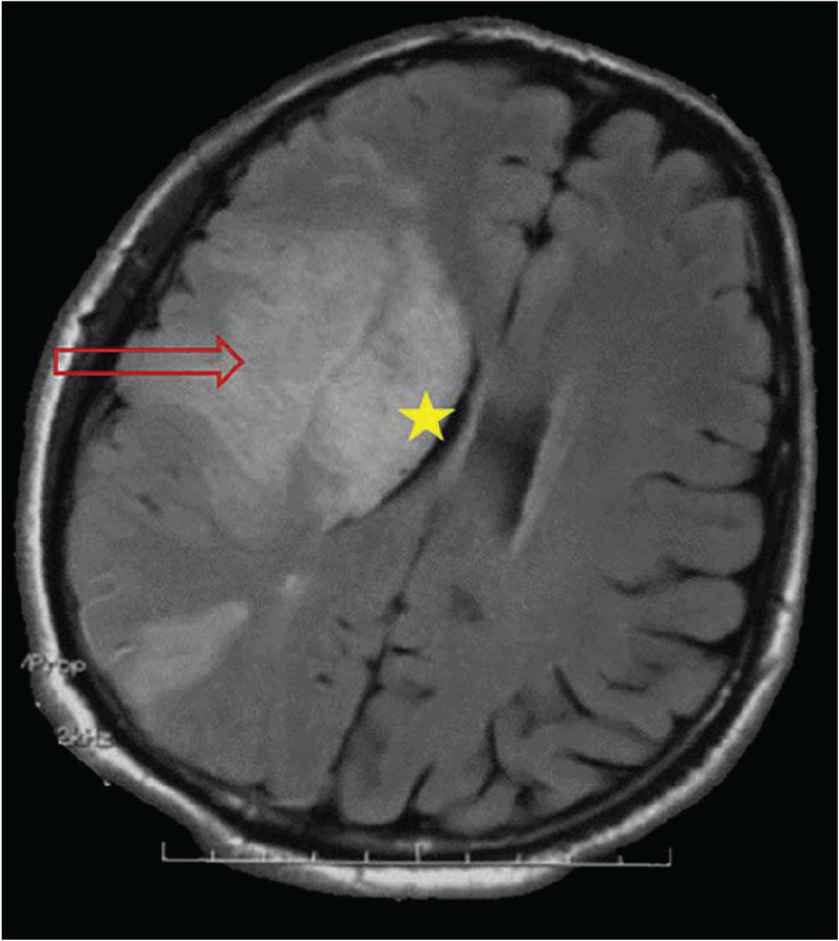

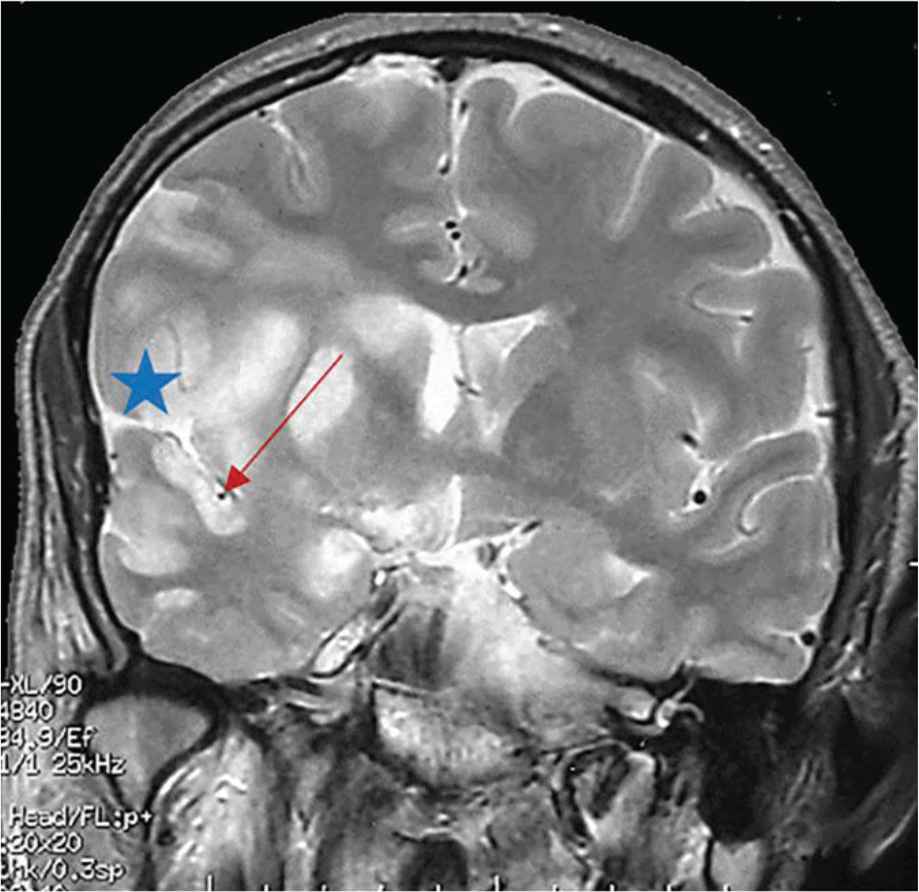

An ophthalmological examination was performed in nine patients and five presented with bilateral papilloedema. Cerebral computed tomography was performed in 13 cases and was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed in six cases, and revealed cerebellitis in one and increased meningeal contrast enhancement in another. It revealed signs of recent ischemic stroke in one case (Figure 1), which was thought to be related to involvement of the right sylvian artery (Figure 2).

Axial section of cerebral magnetic resonance imaging showing a right frontoparietal hypersignal band (arrow) erasing the lenticular nuclei, with a mass effect on the ipsilateral ventricular system (star) secondary to a recent ischemic stroke.

Frontal section of cerebral magnetic resonance imaging showing meningeal enhancement in favor of an arachnoiditis (star) located in the right supracavernous region extended to the Sylvian valley with a right sylvian artery sheathing which has a smaller diameter compared to the left artery (arrow).

Antimicrobial therapy was based on combination of rifampicin, doxycycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in 11 cases, with the remaining cases treated with two-drug combinations, except for No. 7 (Table 3). Adverse effects related to antibiotic treatment were noted in four cases, inducing gastrointestinal problems (Nos. 4, 7, and 14) and toxidermia (No. 7). The median (range) duration of treatment was 4.5 (3–5.3) months. Corticosteroids were administered in three cases.

| Patient No. | Antibiotics | Treatment duration (months) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R + D + C | 4 | Recovered |

| 2 | R + D + C | 3 | Death: ischemic attack |

| 3 | R + D + C | 5.4 | Recovered |

| 4 | R + D + Ca | 5 | Recovered |

| 5 | R + D + C | 4 | Recovered |

| 6 | R + D + C | 5 | Recovered |

| 7 | R + Ca + Cipro | 4 | Recovered |

| 8 | R + D | 8 | Recovered |

| 9 | R + C | 3 | Recovered |

| 10 | R + C | 2 | Recovered |

| 11 | R + D + C | 12 | Sequelae |

| 12 | R + D + C | 8 | Recovered |

| 13 | R + D + Ca | 1 | Death: severe sepsis |

| 14 | R + D + Ca | 5 | Recovered |

| 15 | R + C | 3 | Recovered |

| 16 | R + D + C | 5 | Recovered |

Stopped because of adverse effects.

C, cotrimoxazole; Cipro, ciprofloxacin; D, doxycycline; R, rifampicin.

Treatment protocols and outcomes of patients with neurobrucellosis

Two patients were diagnosed with tuberculosis meningitis–NB co-infection (Nos. 2 and 5). The diagnosis of co-infection with tuberculosis was suspected because of partial improvement of clinical symptoms while the patients received antibrucellar treatment. It was confirmed with a positive polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in CSF (No. 5). Case 2 received 45 days of antibrucellar treatment with no improvement, that’s why a control lumbar puncture was performed, confirming lymphocytic pleocytosis with persistent low CSF glucose level. Antitubercular therapy was, therefore, initiated.

Favorable evolution was noted in 13 cases. Mortality was noted in two cases (Nos. 2 and 13), which was not linked to NB. Two months after recovering from NB, one patient (No. 4) presented with brucellar spondylodiscitis. Sequelae were noted in Case 11, represented by sensorineural hearing loss confirmed by audiogram and walking deficit (Table 3).

4. DISCUSSION

Although rare, NB remains a challenging disease due to its nonspecific clinical features and low index of suspicion. The most common clinical presentation is meningitis. Brucellosis is a ubiquitous zoonosis worldwide that has been re-emerging in the past few years [3,10]. In Tunisia, the mean incidence of human brucellosis decreased from 354/100,000 cases in 2004 to 284/100,000 cases in 2005 [11]. NB may occur during the acute phase of the disease or a few months later [12]. Our data indicated that 10.5% of brucellosis patients had NB, which is consistent with previous reports suggesting NB in 3–25% of human brucellosis cases [13,14]. The most frequent clinical presentations are meningitis and meningoencephalitis [15,16]. Patients usually consult for intermittent fever, progressive headache, lethargy, sleep disorders, and seizures [11,17]. Nonspecific symptoms of meningeal involvement have been reported in NB [18]. Cranial nerve paralyses have been reported more frequently during the acute/subacute phase and associated with diffuse central nervous system involvement. The acoustic nerve is the most frequently involved cranial nerve [19,20].

The most common cause of neurological emergency is cerebrovascular disease. In fact, NB mimicking cerebrovascular accidents has been reported in the literature [21]. Among NB complications, hemorrhage, transient ischemic attack, and venous thrombosis have been reported [22,23]. Cerebrovascular involvement in NB is explained not only by the rupture of a mycotic aneurysm, but also by vascular inflammation, resulting in lacunar infarcts, small hemorrhages, or venous thromboses [24]. In our study, an ischemic attack as a complication of NB was reported in one case.

Neurobrucellosis has neither typical clinical presentation nor specific findings. The detection of any antibodies in CSF provides evidence of NB but, CSF agglutinins may be absent in some cases [25]. Brucellosis induces humoral and cellular immunity, which may explain the lymphocytic pleocytosis [26]. Elevated CSF protein levels have been reported [27]. CSF glucose level might be normal or low, even after treatment [6,28]. However, in NB, CSF may also be normal in 84.6% of cases [29]. The detection of specific antibodies in CSF is important for NB diagnosis. Our data indicated that the growth of Brucella in CSF was reported five cases, which is consistent with previous reports suggesting that cultures of CSF were positive in less than 50% of cases [30]. Because the isolation rate of Brucella species from CSF is low, most cases of NB are diagnosed by serological methods, including an agglutination titer >1/80 in blood and >1/32 in CSF [11,31]. However, the antibody titer in CSF for NB diagnosis remains debatable. In order to confirm the diagnosis, a titer ≥1/80 in CSF is required [32,33], whereas any antibody titer detected in CSF was accepted as diagnostic in some other studies [16,30,34–37]. Although Wright’s serum agglutination test is often used [38], its major inconvenience is the frequent occurrence of crossreaction between Brucella and other bacterial species including Yersinia enterolitica, Escherichia spp. and Salmonella spp. [39]. A high index of suspicion may require repeating the serological test. In fact, negative agglutination test at the onset of symptoms can turn out to be positive later and the diagnosis of localized brucellosis is therefore confirmed [25,40].

Four imaging findings during NB have been reported: normal, inflammation (abnormal enhancement), white matter changes and vascular changes [17]. Granulomatous formation, resulting from inflammation, is a rare manifestation in NB [41]. Imaging findings include arachnoiditis, cerebral turgescence signs with collapsed ventricles or diffuse periventricular or subcortical white matter signal abnormalities [11,17], which may indicate the presence of cerebral/cerebellar abscesses, or less frequently intramedullary abscesses that mimic pyogenic or tuberculous abscesses [17,42–44].

The treatment of NB is still controversial [25]. No consensus exists on regimens and duration of treatment [21,45,46]. Recent reports recommend a regimen with a combination of three or four antibiotics for NB [20]. Antibiotics should be prescribed for at least 2 months. In fact, the treatment duration depends not only on improvement of clinical symptoms, but also on the CSF response [13,47]. An abnormal CSF response is indicative of continuation of antibiotics for 6 months or even 2 years [45]. The use of corticosteroids with antibiotics is indicated for severe presentations including arachnoiditis, cranial nerve involvement, myelopathy [13,48], intracranial pressure, optic neuritis [48,49], or papilloedema occurring on its own [14,50].

5. CONCLUSION

Diagnosis of NB can be challenging due to its nonspecific clinical manifestations and myriad presentations. In cases of unusual neurological disorders, NB should be considered, especially in endemic areas. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial in order to avoid serious complications and sequelae.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

KR, FH, MK and MBJ contributed in study conceptualization, designing and writing. KR and FH contributed in data collection. FH, MK, AC and FS contributed in formal analysis. KR and FH wrote the original draft. MK, EE, CM and MBJ supervised the project. All the authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Khaoula Rekik AU - Fatma Hammami AU - Makram Koubaa AU - Amal Chakroun AU - Fatma Smaoui AU - Emna Elleuch AU - Chakib Marrakchi AU - Mounir Ben Jemaa PY - 2020 DA - 2020/10/16 TI - The Re-emergence of a Forgotten Disease: Neurobrucellosis JO - Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Journal SP - 190 EP - 195 VL - 2 IS - 4 SN - 2590-3349 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/dsahmj.k.201010.001 DO - 10.2991/dsahmj.k.201010.001 ID - Rekik2020 ER -