A Method of Naimaze of Narratives Based on Kabuki Analyses and Propp’s Move Techniques for an Automated Narrative Generation System

- DOI

- 10.2991/jrnal.k.190829.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Kabuki; naimaze; multiple narrative structures; integrated narrative generation system; Geino information system

- Abstract

Naimaze in kabuki has been known as a narrative creation method, or a group of techniques that combines components in existing kabuki works or in the narratives from other genres for making a new work. Various elements, such as stories, plots, characters, and places, can be used as components in naimaze. The author aims to use the naimaze method in automated narrative generation systems that we have been developing, namely the Integrated Narrative Generation System (INGS) and the Geino Information System (GIS). In this paper, the author first presents an approach to design the narrative techniques of naimaze in the INGS (and GIS) by applying the method for combining “moves” as explained in Propp’s narratological study, “morphology of the folktale.” A move by Propp means a narrative macro level unit, or a kind of sequence that is composed of several “functions;” and he showed various ways to combine several moves to construct an entire narrative structure. The next section discusses the many possibilities of naimaze techniques and the implementation of experimental programs based on various kabuki analyses; and the utilization of the Propp’s move method as a preliminary attempt for naimaze techniques in the INGS and GIS. This paper also outlines the direction of future research for designing and implementing an organized naimaze technique group. In addition, this paper is a review article that the author’s previous kabuki-related papers are overviewed.

- Copyright

- © 2019 The Authors. Published by Atlantis Press SARL.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The author has been studying kabuki [1–5] to introduce the acquired narrative knowledge and a wide range of techniques into two types of mutually related narrative generation systems, called the Integrated Narrative Generation System (INGS) [6,7] and the Geino Information System (GIS) [8]. In particular, the author has been studying kabuki from the viewpoint of multiple narrative structures or the multiple narrative structure model [6,7]. The generation process of a narrative work and the repetitive production process of several narrative works can be considered from the viewpoint of generation and production through multiple narrative structures. For example, a narrative’s generation flow comprises the multiple structures of a story at a semantic level and a plot at a constructive level.

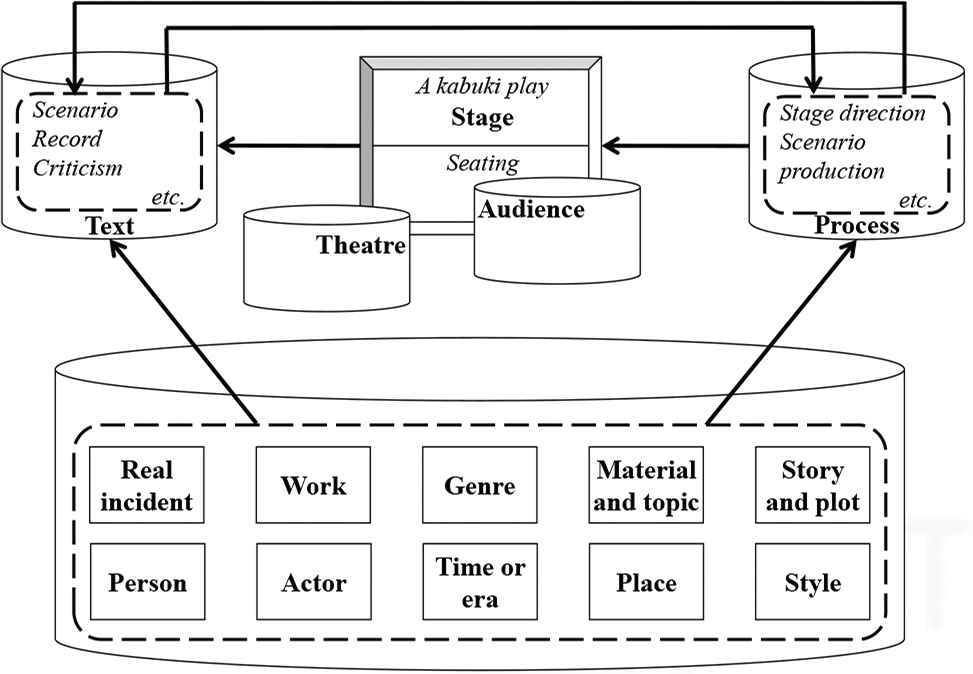

The author considers a kabuki narrative as a particularly rich object for the multiple narrative structures model. In the first step of studying kabuki as a means of narrative generation and production, the author has analyzed the multiplicity of kabuki with regard to the following fifteen kinds of elements shown in Figure 1. This figure also shows the overview of the relationship between the INGS and GIS. For instance, the element of a “person” in kabuki can be divided into the following three aspects: the real “person” who lives in the actual world; the “person” as an actor who has a history of performing roles; and the “person” of the kabuki character that appears on stage. Each person has their own history or story.

Multiple narrative structures of kabuki and INGS and GIS (Source: Ogata [8]).

Naimaze in kabuki has been known as a narrative creation method or a group of techniques that combines components in existing kabuki works or in the narratives from other genres for making a new work. Various elements, such as stories, plots, characters, and places, can be used as components in naimaze. The author aims to use the naimaze method in the INGS and GIS. In this paper, after the author describes our previous studies in kabuki narrative generation as background information, the author presents an approach for designing the narrative techniques of naimaze for the INGS (and GIS) by applying the method for combining “moves” as explained in Propp’s [9] narratological study, “morphology of the folktale.” A move by Propp means a narrative macro level unit, or a kind of sequence that is composed of several “functions;” and he showed various ways to combine several moves to construct an entire narrative structure. The next section displays many possibilities of naimaze techniques and the implementation of experimental programs based on various kabuki analyses; and the Propp’s move method is utilized as a preliminary attempt for naimaze techniques in the INGS and GIS. This paper, further, shows the direction that will be taken by future research when designing and implementing an organized naimaze technique group in these systems based on our future kabuki studies. In addition, although modeling naimaze in kabuki using the Propp’s folktale theory is the author’s original idea, this paper is positioned as a review article that surveys and overviews the kabuki’s narrative generation study by the author because this paper contains many other descriptions for providing information regarding the author’s kabuki-related narrative generation study to the readers.

2. BACKGROUND

Previous kabuki studies by the author include the following topics:

- (1)

Preliminary and comprehensive considerations regarding kabuki and narrative generation.

- (2)

An entire framework of the multiple narrative structures of kabuki.

- (3)

Studying and considering several topics, including “person,” “story,” and “tsukushi,” in the multiple narrative structures of kabuki.

- (4)

Introducing knowledge acquired from research, analyses, and considerations of kabuki into our narrative generation systems (INGS and GIS).

In (1) [10–12], the author has studied the history and characteristics of kabuki and considered the narrative methods or techniques for connecting them to our narrative generation research.

The Japanese for kabuki (歌舞伎 or 歌舞妓) consists of the three Chinese characters: “song” (ka, 歌), “dance” (bu, 舞), and “acting” (ki, 伎 or 妓). At the same time, the term originated from the verb kabuku (かぶく, 傾く), meaning “to incline” and “lean away.” The word generally implies strange, unusual, or unconventional styles; and it has shaped the mental image of the tradition of kabuki. A kabuki play is a collection of a variety of narratives: namely, it has the appearance of a multiple narrative structure in the sense that its whole is a multiple structure; therefore, its narrative generation should comprise a combination of several narrative generation processes. At the same time, a kabuki play forms multiple narrative structures in the sense that it contains narrative structures in various levels. Kawatake [3] maintains that kabuki has a “chimeral nature” because of its amalgamation of diverse elements in a wide variety of aspects. This chapter will approach the elements from the viewpoint of a system that integrates various mechanisms or processes.

In the next point (2) [13–16], the author has presented an entire framework of the multiple narrative structures of kabuki that comprise the multiple structures among the components, the multiple structures in each component, and the multiple structures for synthesizing their multiplicities, in order to understand and deal with a whole system of kabuki from the viewpoint of the multiple narrative structures model of kabuki. Table 1 shows current fifteen multiple elements of kabuki (the description is a summary of Ogata [8,16].

| Name | Overview |

|---|---|

| (1) Real incident | Stories or plots in kabuki are very often constructed based on actual or real incidents, for instance, historically famous events and facts for jidai-mono. On the other hand, sewa-mono frequently uses contemporary events in the daily life of ordinary people. Typically used historical sets of events have been repeatedly introduced and arranged in many kabuki works. The relationships between a real incident and its fictionalization were diverse and complex. The fictional parts of a real incident, such as a character’s formation, have sometimes had a large influence on making people’s imaginings. |

| (2) Work | Through the historical development process of kabuki, a work was often adapted to other works using various types of methods for editing and revision. Although influential relationships among works are also ordinary phenomena in the current artistic environment, very quick and active transformational phenomena, especially in the Edo era, would have partially relied on the lack of awareness of copy-writing. However, a more essential and practical reason for such an outstanding production style was that the revision of a work was easy to adapt to the unique characteristics of author, theatre, actor, and troupe. |

| (3) Genre | Creating a new work based on one or more past works in the same or another genre was a commonly used method in Japanese dramatic or geinō genres such as nō and ningyō jōruri. This method of creation reached a unique and extreme level in kabuki. Kabuki can be considered a synthetic collection of diverse previous geinō genres, including nō, kyōgen, and ningyō jōruri as dramatic geinō genres |

| (4) Material or topic | Materials or topics commonly used in many kabuki works already exist, which have been categorized under many groups. The explanation by the author will seek to address this characteristic of kabuki in the framework of the circulative evolution process of kabuki. For instance, when a kabuki work is created using certain existing material, and subsequent work is produced based on such editing of a previous work, the latter work forms a variation of the former while using the same material or topic as the original work. This continuous flow has produced many groups of kabuki works according to the same respective materials. Although this may be similar to the theme of “real incident,” the material or topic referred to here is not necessarily a “real” incident. Fictional events were also utilized. Further, “real” and “fictional” can be changed through a kabuki generation sequence or the circulative evolution process. A kabuki work that is created from a real incident or event serving as material can change or transform the event to the level of an event as fictional narrative. |

| (5) Person | “Person” in kabuki is mainly divided into the level of an “actor” who plays on the stage and that of a “(dramatic) character” in the narrative of the work. The two types of persons form multiple relationships on the temporal and spatial levels. First, a person plays a dramatic character in a kabuki play; at the same time, the existence accompanying the real name also has essential meaning. In kabuki, the aspect of “an actor plays” frequently has a more important meaning than representing a universal drama or story. A kabuki scenario in the Edo era was not originally written with the names of characters in the story, but with the names of the actors who really played the drama. In other words, in classical kabuki works, a scenario was ordinarily written according to the characteristics of the actors; therefore, the actors were not selected on the basis of any artistic viewpoints based on a preliminarily written scenario. There were many critics of the weak points of such kind of star system. And after the Meiji era, scenario-centered drama production also became a popular method. However, the tradition of the star system emphasizing the actors has also remained in contemporary kabuki. |

| (6) Story and plot | In kabuki narratives, in the wider sense used by the author, difficulty in perception may be caused by the multiplicity derived from the various complicated levels. The author sometimes thinks that mechanisms or methods for editing various elements of the levels in kabuki may be associated with a kind of “arbitrariness,” so to speak. However, the multiplicity of kabuki, in which various acts of editing overlap in complicated ways, gains new and unique characteristics beyond the respective original editing acts. Finally, the arbitrariness will change to a kind of “inevitability” or “necessity” through the multiple editing processes. Such characteristics in kabuki often appear in a single element too, e.g., at the level of scenarios, plots, or stories. The “closeness” of the kind of “retribution” stories were a feature in the whole of the Edo literature that differs from modern and contemporary literature. Kabuki amplified the feature through the dramatic bodies of the actors. |

| (7) Actor and place | Watanabe [4] states that a limited number of actors in a theatre troupe have been able to play many repertories of kabuki by performing a variety of dramatic characters. To realize this, a theatre troupe needed to make preliminary preparations and necessary arrangements to construct a variety of places on the stage: stage settings for various fictional places and characters’ costumes for various roles of characters. Both characters and costumes in kabuki are categorized as a patterned system, and the combinations are limited. This mechanism enables an actor to be able to play many different character roles using a limited number of costumes (and the closely related maquillage) and combinatorial processing. Similarly, places on the stages in kabuki can also be constructed by using a limited number of stage settings and combinations. Kabuki plays, as theatrical arts with real constraints of each stage, have manifold combinations of limited stage settings, characters, and costumes. |

| (8) Time (Era or Age) | Different historical times are frequently mixed or overlapping in a kabuki play. Such temporal multiplicity has also been related to the censoring system by the Edo government, in addition to artistic requirements. The direct representation of contemporary events of the same age could not be permitted under the political situation. A work based on a contemporary, real incident repeatedly changed the temporal setting to a past age and was expressed under a different temporal setting, using a sekai of a different age. The change and movement of time and era was simultaneously connected to the change of spatial elements—the components for space and place. An interesting phenomenon regarding temporal and spatial change is that it creates an overlapping of spaces and characters from different historical times. |

| (9) Style (Form or Pattern) | “Style” is here used to mean “performing style,” in which various styles appeared to be adopted on the actual stages in kabuki plays, such as for dance, music, narration, and action forms or patterns by actors. There were a variety of multiplicities and possibilities dependent upon the constraint of prepared elements and combinations. The music accompanying the actors’ actions has included many genres, such as nagauta, kiyomoto, tokiwazu, and ō-zatsuma, etc. The narration by a takemoto, corresponding to a tayū in ningyō jōruri, has been transformed for a playing style for human actors instead of one for artificial puppets. While all parts of the scenario of a work are narrated by several tayū in ningyō jōruri, the scenario of a kabuki work is divided into the parts of katari (narration) by takemoto and serihu (speech) by human actors. The artistic blending of kabuki and ningyō jōruri has given birth to another aesthetic technique called ningyō-buri in kabuki, which is a unique performing style in which a human actor imitates or simulates the action of the puppet in ningyō jōruri. This represents one of the interesting and complicated multiple structures in kabuki. |

| (10) Theatre (Stage and Seating) | By Kawatake [3], traditional stage dramas in Japan have incorporated the theatres into necessary components in respective genres. A theatre was not a universal space where all or diverse theatrical genres are performed. In particular, no, ningyō jōruri, and kabuki have basically respective exclusive theatres. According to Kawatake, traditional Japanese plays of a particular genre incorporate the theater as an essential component. The theater/stage exists as a universal space, and it is not that various genres of plays are performed there, but rather, nō, ningyō jōruri (bunraku puppet theater), and kabuki are performed in theaters and stages specifically suited to them. The hanamichi, described in the previous section, is a mechanism on the kabuki stage that has multiple usages. |

| (11) Audience | Kabuki is primarily an object to be viewed in the theatre by the audience. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that only the phenomenon of viewing in the physical space of the theatre can be an absolute experience for the audience. However, it is also certain that kabuki is closely, essentially, and mutually bound with the existence of the theatre. As seen in the examples of the hanamichi and kakegoe in the previous section, the audience also plays a part in the multiple editing of kabuki. The difference between seeing a kabuki play as a movie and in the theatre is considered to be greater than the difference between seeing a movie on television and at the cinema. The viewpoint in a movie has already been prepared based on the creator’s intention and technique. Rather, when an audience views a movie at the cinema, the viewpoint in the work does not change according to the place in which the audience views it. On the other hand, in the case of kabuki, there are various different viewpoints according to the place in the theatre. |

| (12) Text | Reading or receiving a novel or a poem is an experience involving a person reading words that are physically represented on the paper, and the text in such case means the enumeration of the words themselves. In contrast, receiving a drama on the stage is, in the primary sense, to perceive humans’ physical actions around the stage settings and decors. Unlike a book, a drama on the stage is not a representation solely based on the enumeration of words, but is also a collection of body actions and sometimes the stage itself accompanying these actions. Kabuki has a tradition of essays and criticisms originating from the yakusha hyōbanki in the Edo era, which was a series of books that commented on the kabuki actors. The style has been persistently dependent upon the fact that an audience really views a kabuki play on the stage in a theatre. This fact indicates that the text in kabuki has been the individual stage performance as a collection of body actions by actors and stage settings. This tradition has not yet been corrupted on the present kabuki scene. |

| (13) Production of Scenario (“Daichō”) | The production of actual performance scenarios, which in the book of a scenario is called daichō, was very simple in the initial days of kabuki because the typical works, which had only a single structure containing but a few scenes, were not completed dramas but an assortment of entertainments and dances. However, kabuki works gradually came to have large-scale and complicated structures. The production mechanisms also developed to become more systematic, thanks to excellent authors, especially from ningyō jōruri, such as Chikamatsu Monzaemon and Ki-no Kaion. As a result, a new type of scenario production style was invented through which several authors created a scenario working collaboratively. |

| (14) Direction | The property of kabuki plays whereby various different historical ages and places of a narrative are mixed rather than representing a realistic standard influences the production of each actual stage. Various styles of blending or overlapping of costumes, language of speech, music, etc., sometimes exceed ordinary situations. Maquillage or the make-up and costumes of characters are designed according to the form or kind of traditional norm to be used for each typical character. Such very symbolic and formal features frequently ignore the realistic consistency and naturalness of the entire staging. One of the reasons may certainly be the disordered confusion of forms through historical accumulation. Innovative plans to return realistic styles of play to kabuki have actually been proposed by some actors. However, since over-realistic and symbolic styles form a tense tradition and also a unique beauty involving the audience, kabuki grew into a more heterogeneous and synthesized dramatic genre than one of pure realism. |

| (15) Stage performance | Kabuki in the Edo era was a contemporary drama of that age. Therefore, each kabuki play was basically performed in the style of tōshi-jōen, which means that all of the parts are played continuously, in 1 or 2 days. However, in truth, the actual form was not necessarily simple as there were complex rules or performing systems. A basic pattern was that two types of newly created works of jidai-mono and sewa-mono were mutually played in the program for a series of kabuki performances. By contrast, after the Meiji era, the midori-jōen—a new performing style in which mainly the classical works of Edo kabuki were repeatedly performed—gradually spread and became popular, though many new works (scenarios), including the sub-genre of shin-kabuki (“new kabuki”), were also written by many modern authors. |

Kabuki’s multiple elements

The objectives of (3) include deeper analysis and study of each component of the above-mentioned multiple narrative structures and an in-depth consideration of the multiple connections or relationships of these kabuki components. In particular, the author has considered through investigations regarding “person” [17] and “story” [18]. However, tsukushi or zukushi [19] is not included in the current list of the multiple narrative structures (Figure 1). By the term tsukushi (or zukushi), the author means a thorough, or often exhaustive, description of a group of objects, including places such as mountains and cities, objects such as fish and foods. Naimaze descriptions frequently appear in Japanese classical literature, such as novels, stories, and long poems; and geino works, such as dances, ningyō jōruri works, and kabuki works. Gunji [20] regarded basho zukushi (the tsukushi of places), such as michiyuki (a symbolic travel scene), as a type of kabuki esthetics that is propagated through the Japanese literary and geino traditions. Gunji discussed basho zukushi in kabuki from the viewpoint of unique arrangements between spatial and temporal aspects in a narrative, different from the emakimono style in which the temporal aspect is superior. The author understands zukushi or tsukushi as an important element in the multiple narrative structures of kabuki. On the other hand, it is located in a meta-level element that crosses 15 kinds of elements shown in Figure 1.

The final point (4) aims to introduce knowledge acquired from research, analyses, and considerations of kabuki into our narrative generation systems (INGS and GIS) [18]. One of the objectives of the study of kabuki’s narrative generation by the author is to comprehensively and precisely describe a “kabuki narrative generation system model.” According to this macro objective, one of the present goals is to introduce the acquired kabuki narrative knowledge, methods, and techniques into mutually related systems, the INGS and GIS.

3. NAIMAZE: THE USAGE OF PROPP’S MOVE METHOD FOR MIXING NARRATIVES

Naimaze in kabuki has been known as a narrative creation method or a group of techniques that combines components in existing kabuki works or in the narratives from other genres for making a new work. Various elements such as stories, plots, characters, and places can be used as components in naimaze. Although the narrative and theatrical techniques of naimaze were systematically established by Tsuruya Namboku IV, one of the greatest kabuki writers, naimaze was organized systematically through meetings and collaborations among various participants of a kabuki production. First, when a new kabuki work is created, a sekai (world) that is a set of materials as the framework of the work is selected or determined. A sekai contains one or more old legends, geinō genres, literary works, narratives, and so on in which dramatic characters and historical people, who are friendly to the period’s audiences, appear. In detail, a sekai also includes historical backgrounds, places, names and characteristics of characters, human relationships, and macro patterns of stories. After a sekai is decided, various techniques (shukō) are added to the framework of sekai. The shukō is the originality or creativity that is unique to each kabuki writer. In kabuki, this was a popular characteristic using both narrative frameworks that many audiences commonly held and literary and artistic originality and creativity. In the techniques of shukō, patterned scenes or episodes also exist, such as migawari (substitute or sacrifice), koroshi (killing), and enkiri (dissolution). As well, contemporary, vivid events such as killing, burglary, and shinjū (double suicide), are frequently used in a sekai. Here, naimaze means a special technique or a group of techniques through which several sekais are simultaneously combined each other.

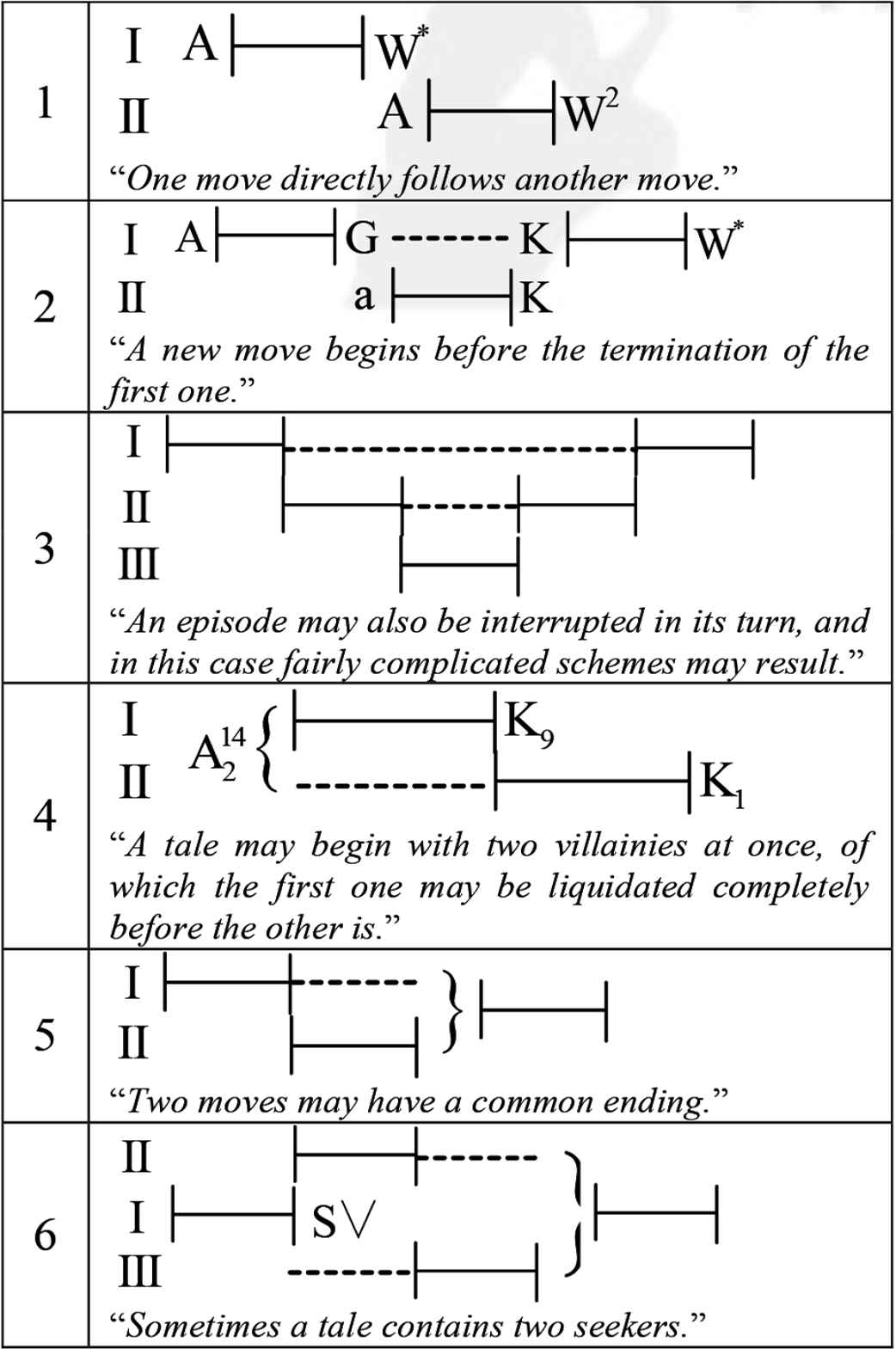

The author presents a method for simulating naimaze in kabuki based on our previous paper [21] related to Propp’s [9] folktale theory. Propp presented a method of combining stories using several patterns of combining “moves.” In Propp’s narratological theory, the most basic narrative units for folktale-like stories are 31 kinds of “functions.” A move is composed of the selective sequence of functions and many actual folktales are combinations of several moves. Table 2 shows examples of the combination patterns of moves as proposed by Propp. The author’s idea is to implement the naimaze in kabuki by using Propp’s move method.

Move combination patterns (Source: Ogata and Hosaka [21])

The following descriptions provide the explanations and texts for three types of examples of naimaze using Propp’s method. These examples are not the results of automatic generation, but human attempts:

- •

[Example 1: Narukami + Sanmai no Ofuda] The first example shows that a folktale story, Sanmai no Ofuda [22] is based on the story of a kabuki work, Narukami [23] using the method 1 in Table 1. In particular, Sanmai no Ofuda (second part) is connected to Narukami (first part) and the main characters in Sanmai no Ofuda are changed to the characters in Narukami.

- •

- •

[Example 3: Characters in Sukeroku → Characters of Gogo no Eiko] The final example deals with the naimaze of characters only. This example does not use the Propp’s method. In particular, in the story of Sukeroku [25] of kabuki, the characters are replaced by the main characters in Gogo no Eikō [26] by Yukio Mishima, the chief, Fusako, Ryūji, Noboru, and Yoriko.

[Example 1] The rain has stopped falling and the whole country is suffering from a drought. This is because Narukami Shonin (a priest) holds a grudge against the Emperor for not keeping his promise, and has caged the dragon god of rain behind a waterfall. A beautiful young woman appears, heading for Shonin’s hermit cave in the northern mountain. She says that she wants to wash the clothes of her dead husband in which her feelings for him linger, but because there is no water, she has come to the waterfall to find the water to wash the clothes. To say farewell to her husband, the woman crosses the river toward Shonin, and lifts up the hem of her skirt to reveal her white legs, and without thinking, Shonin bends forward toward her. To the suspicious Narukami Shonin, the woman turns and says that she wants to become a nun and his disciple. Shonin sends out his two disciples, Hakuunbô (the white cloud bonze) and Kokuunbô (the black cloud bonze) to bring her nun garments, and then the woman suddenly becomes sick. The surprised Shonin attends to her, and while doing so he touches her breast. He has never touched a woman before and he is gradually unable to control his desire due to the softness of her skin. Seizing her chance, the woman brings out to drinking cups and gets Shonin drunk, and in his drunkenness he reveals that he keeps the dragon god imprisoned behind a sacred rope across the waterfall. As Shonin sleeps drunkenly, the woman creeps away and cuts the rope and releases the dragon god, and immediately it begins to rain heavily. The woman was in fact Kumonotaema Hime (Princess), the most beautiful woman at the court, sent by the Emperor to break the power of Narukami. When he revives and becomes aware of what happened, his hair stands on end and he becomes enraged, he turns into flames, he fights and knocks down the disciples who attempt to stop him, and he chases after the princess. The princess, who can see Narukami chasing after her, throws down the second paper charm and says a curse, “Make a big river appear behind me,” and sure enough, a big river appears. But Narukami uses his magic powers to swallow the water in the river. Next, the princess uses her final charm and says the curse, “Make a sea of fire appear” and a sea of fire appears. But Narukami uses the water he has swallowed to put out the sea of fire. The princess hurries back to the temple and seeks the help of the priest, who makes her promise to train more seriously after that, and hides her in a large pot. The priest begins baking rice cakes in the hearth. Then Narukami enters the temple and demands that the priest give him the princess. The priest says that before that, let’s see which one of us is the best at changing shapes. He asks “Can you make yourself as big as a mountain?” “Yes I can” replies Narukami, and makes himself as big as a mountain. The priest then asks, “Can you make yourself as small as bean?” “I can do that too” Narukami replies, and makes himself as small as a bean. The priest picks up Narukami, who is now the size of a bean, stuffs him in the rice cake he is baking, and eats him.

[Example 2] Once upon a time there was a temple in a village, in which lived a young monk and a Buddhist priest. One day the young monk said to the priest that he wanted to go to the mountain to collect chestnuts. The priest takes out three charm cards and gives them to the young monk. The young monk goes to the mountain and becomes so absorbed in collecting chestnuts that he is still on the mountain when the sun goes down. Then, an old woman appears and invites the young monk to stay at her home. But during the night, the boy wakes up and sees the woman in her true form of a mountain witch, sharpening a knife in the kitchen preparing to eat him. The young monk says “I want to use the toilet,” so the mountain witch thinks about it, and ties him up with a rope and takes him to the toilet. The young monk attaches one of the paper charms to a pillar in the toilet, and says “Pretend to be me and answer the witch,” and he flees out of the window. The witch asks “Are you finished?” and the paper charm replies in the voice of the young monk, “Just a little longer.” The witch then asks again, “Are you finished?” and the paper charm again replies in the voice of the young monk, “Just a little longer.” Finally, the witch cannot stand it any longer and breaks down the door of the toilet, to find that the young monk has disappeared without a trace and there is only the torn paper charm. Realizing she had been tricked, the witch chases after the young monk. The young monk, who can see the witch chasing after him, throws down the second paper charm and says a curse, “Make a big river appear behind me,” and sure enough, a big river appears. But the witch uses her magic powers to swallow the water in the river. Next, the young monk uses his final charm and says the curse, “Make a sea of fire appear” and a sea of fire appears. But the witch uses the water she has swallowed to put out the sea of fire. The young monk hurries back to the temple and seeks the help of the priest. The young monk and his party are trying to pass, with the priest taking the lead, wearing the disguises of yamabushi mountain priests. The priest says that they are travelling to seek donations for the rebuilding of the destroyed Todaiji Temple. However, already the information has been delivered to the barrier keeper, Saemon Togashi, that the young monk and his party are travelling disguised as mountain priests, and he gives the strict order that no mountain priests are to be allowed to pass. Indignant at this, the priest and his friends chant an esoteric Buddhist prayer to Togashi, to attempt to clear his suspicion. This impresses Togashi and is reminded of the previous words of the priest, and he orders him to read the kanjincho (a subscription list of people who have donated). The priest pulls out a blank scroll that he happens to have and spontaneously begins to read it, pretending it is the kanjincho. But Togashi is still suspicious, and asks him difficult question about the life of a yamabushi disciple and about esoteric prayers, but the priest answers without hesitating. Togashi lets them pass, but still has strong doubts about one of the lower-ranked men in the group, who is actually the young monk. The priest beats his master the young monk with his pilgrim’s staff, which clears him of suspicion. The young monk, who had escaped from danger, compliments the priest for his quick thinking, but the priest bursts into tears and apologizes to his master for the rude way he had to save his life. Responding to this, the young monk gently takes the priest by the hand and has him think of the story of the battle in which they pursued Taira together. Then Togashi appears and apologizes for his previous rudeness and offers them sake to drink. The priest drinks the sake and performs a dance. The young monk and his party escape while the priest dances. The priest puts on his oi (a wooden box carried on one’s back to store items for a pilgrimage) takes his leave of Togashi, and hurries after his master. Then the mountain witch enters the temple and demands that the priest gives her the young monk. The priest says that before that, let’s see which one of us is the best at changing shapes. He asks “Can you make yourself as big as a mountain?” “Yes I can” replies the witch, and makes herself as big as a mountain. The priest then asks, “Can you make yourself as small as bean?” “I can do that too” the witch replies, and makes herself as small as a bean. The priest picks up the witch, who is now the size of a bean, stuffs her in the rice cake he is baking, and eats her.

[Example 3] Soga no Goro, who appears as a guest named Hanakawado Noboru, goes to Yoshiwara (the entertainment district) to search for Genji’s treasured sword “Tomokirimaru.” In Yoshiwara, which is a place where various men gather, he intentionally tries to start fights with men so that they will draw their swords, revealing if they have the sword he is searching for. Fusako is a courtesan who is frequented by Noboru, and the magnificently bearded Ryūji also appears with Fusako. Noboru thinks that Ryūji might have Tomokirimaru and tries to get him to draw his sword, but he is unable to. Noboru’s older brother, the chief, than appears as a seller of white sake, and on hearing the opinion of his younger brother, he himself starts trying to pick fights. Soon Fusako returns to the stage accompanied by a samurai. Noboru tries to pick a fight with the samurai, but surprisingly that samurai is his mother, Yoriko, in disguise, who has come because she is worried about the two brothers. Yoriko dresses Noboru in an easily breakable paper kimono and warns him against a fierce fight, and they return to the chief. Ryūji once again appears on the stage. Ryūji sees that Noboru is actually Soga no Goro, draws Tomokirimaru and tries to persuade him to betray Genji. Noboru of course does not agree to this, cuts-down Ryūji, retrieves Tomokirimaru, and leaves Yoshiwara.

4. FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

In the future, the author will design and implement the naimaze techniques for narrative generation in the INGS and GIS in accordance with the following directions:

- •

Positioning of naimaze in the multiple narrative structures model of kabuki: Naimaze is made to correspond to the positioning of the meta-level concept for 15 topics of the multiple narrative structures. Naimaze is not an element that is included in the topics and is regarded as a kind of narrative technique that, so to speak, utilizes several elements in the topics in the meta-level and traverse. For example, although applying a naimaze method or technique to a story or plot is the most general usage, naimaze is also related to the element of a “character” as in a “person.” In particular, though it is a possibility of naimaze to mix “stories” or “plots” of two or more narratives, the usage of the naimaze of “stories” or “plots” is related to the naimaze of “characters” of different works. Similarly, introducing “characters” from different existing works into a new work enables the associative relationship of the new work to past works.

- •

Narrative elements that enable diverse naimazes: The most basic mechanism of naimaze is related to, or needs, the consideration of the following aspects: (1) object, (2) basic method or technique, and (3) strategic method or technique. The first necessary step for implementing naimaze techniques is to make these issues clear at the macro design level. Regarding (1) “object,” in the elements of the multiple narrative structures of kabuki shown in Figure 1; “real incident,” “work,” “material and topic,” “story and plot,” “person,” “time or era,” and “place” can be considered the objects of naimaze in the ordinary sense. Furthermore, as a possibility, “text,” “genre,” “actor,” and “style” may also become the objects. Regarding (2), “basic method or technique” comprises a group of formal methods or techniques for conducting the naimaze of each object. Further, there are naimaze methods or techniques for simultaneously processing several objects. At the most formal level, namely methods or techniques in the program’s implementation level here, functions called narrative techniques, which expand or transform a story structure or narrative discourse structure generated by the INGS, can also be utilized for naimaze. This means that naimaze’s techniques can also be located as a group of narrative techniques in the INGS. Additionally, concrete knowledge of kabuki and the other narratives is required for designing and implementing naimaze methods or techniques. This kind of knowledge, namely, kabuki-oriented knowledge, can be stored in the GIS as a part of the author’s framework of narrative generation. Naimaze’s methods and techniques can be designed and implemented through mutually related narrative generation systems, the INGS and GIS. Finally, (3) “strategic method” means a kind of control mechanism that enables the effective use of naimaze. In addition to an ordinary plan in which previously defined strategic control methods are used for naimaze generation, another idea of the author concerning this problem is to prepare a different control method that executes random narrative generation, naimaze in this case, and incrementally narrows down the range of generated narratives through repetition and storage of the evaluation of the results and process [27].

5. CONCLUSION

The author has been conducting a synthetic study of narrative generation systems based on mutually relating two systems, the INGS and GIS. Naimaze methods or techniques of kabuki dealt with in this paper will be introduced into these narrative generation systems in the future. In this paper, the author proposed several basic methods of naimaze using our previous research based on the move connection theory by Propp. Next, the author listed several future issues for introducing naimaze as a group of narrative techniques into the INGS and GIS. These issues, at the same time, can be designed and implemented on the basis of the author’s research results and ideas shown in this paper, including the multiple narrative structures of kabuki and the narrative generation through random generation and continuous evaluation. Finally, as a review article, this paper comprehensively surveyed and overviewed the kabuki-related narrative generation study by the author in addition to present a technical idea for implementing an aspect of naimaze in kabuki as narrative generation techniques.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by

Author Introduction

Dr. Takashi Ogata

He received his PhD in the University of Tokyo in 1995. He has industrial experience since 1983 at software development companies. He is a Professor of the Faculty of Software and Information Science at Iwate Prefectural University since 2005.

He received his PhD in the University of Tokyo in 1995. He has industrial experience since 1983 at software development companies. He is a Professor of the Faculty of Software and Information Science at Iwate Prefectural University since 2005.

His major research interests include artificial intelligence, cognitive science, natural language processing, narratology and literary theories, an interdisciplinary approach to the development of narrative generation systems based on AI and narratology, and the application to narrative creation and business

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Takashi Ogata PY - 2019 DA - 2019/09/18 TI - A Method of Naimaze of Narratives Based on Kabuki Analyses and Propp’s Move Techniques for an Automated Narrative Generation System JO - Journal of Robotics, Networking and Artificial Life SP - 71 EP - 78 VL - 6 IS - 2 SN - 2352-6386 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jrnal.k.190829.001 DO - 10.2991/jrnal.k.190829.001 ID - Ogata2019 ER -