Clinical Characteristics and Predictors of 28-Day Mortality in 352 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Study

, Fahad Faqihi1, Abdullah Balhamar1, Feisal Alaklobi2, Khaled Alanezi1, Parameaswari Jaganathan3,

, Fahad Faqihi1, Abdullah Balhamar1, Feisal Alaklobi2, Khaled Alanezi1, Parameaswari Jaganathan3,  , Hani Tamim4, Saleh A Alqahtani5, 6,

, Hani Tamim4, Saleh A Alqahtani5, 6,  , Dimitrios Karakitsos1, 7,

, Dimitrios Karakitsos1, 7,  , Ziad A Memish3, 8, 9, *

, Ziad A Memish3, 8, 9, *- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.200928.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- COVID-19; intensive care unit; mortality; active smoking; pulmonary embolism; d-dimers; lactate

- Abstract

Background: Since the first COVID-19 patient in Saudi Arabia (March, 2020) more than 338,539 cases and approximately 4996 dead were reported. We present the main characteristics and outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 patients that were admitted in the largest Ministry of Health Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: This retrospective study, analyzed routine epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory data of COVID-19 critically ill patients in King Saud Medical City (KSMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, between March 20, 2020 and May 31, 2020. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection was confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assays performed on nasopharyngeal swabs in all enrolled cases. Outcome measures such as 28-days mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay were analyzed.

Results: Three-hundred-and-fifty-two critically ill COVID-19 patients were included in the study. Patients had a mean age of 50.63 ± 13.3 years, 87.2% were males, and 49.4% were active smokers. Upon ICU admission, 56.8% of patients were mechanically ventilated with peripheral oxygen saturation/fraction of inspired oxygen (SpO2/FiO2) ratio of 158 ± 32. No co-infections with other endemic viruses were observed. Duration of mechanical ventilation was 16 (IQR: 8–28) days; ICU length of stay was 18 (IQR: 9–29) days, and 28-day mortality was 32.1%. Multivariate regression analysis showed that old age [Odds Ratio (OR): 1.15, 95% Confidence Intervals (CI): 1.03–1.21], active smoking [OR: 3, 95% CI: 2.51–3.66], pulmonary embolism [OR: 2.91, 95% CI: 2.65–3.36), decreased SpO2/FiO2 ratio [OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91–0.97], and increased lactate [OR: 3.9, 95% CI: 2.4–4.9], and

d -dimers [OR: 2.54, 95% CI: 1.57–3.12] were mortality predictors.Conclusion: Old age, active smoking, pulmonary embolism, decreased SpO2/FiO2 ratio, and increased lactate and

d -dimers were predictors of 28-day mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients.- Copyright

- © 2020 The Authors. Published by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) disease (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China, and spread worldwide. Almost 30 million people were affected and the death toll reached to 1 million cases thus far [1]. The first case of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia was confirmed on March 2, 2020, and since then more than 338,539 cases with more than 4996 dead were reported [2,3]. Although most patients present with mild diseases and recover from the infection, life-threatening disease can occur resulting in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) hospitalization. Severe COVID-19 is characterized by Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, multi-system organ failure, hyperinflammation, neurological and other extra-pulmonary manifestations, and thromboembolic disease [4–14]. Several studies analyzed the factors affecting morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [15–24]. Factors that were correlated with a poor prognosis included old age, the presence of comorbidities such as hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus (DM), morbid obesity, chronic pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and malignancies. Laboratory parameters that were linked to a poor outcome were: lymphocytopenia, and increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, and interleukin-6 amongst others [25–39]. However, only a few studies were focused on the analysis of risk factors affecting morbidity and mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Herein, we present a retrospective analysis of the clinical characteristics and the risk factors, which influenced 28-day mortality post-ICU admission, in three hundred and fifty two critically ill COVID-19 patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Patients

We retrospectively analyzed critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to our COVID-19 designated ICU from March 20, 2020 to May 31, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by Real-Time-Polymerase-Chain-Reaction (RT-PCR) assays, performed on nasopharyngeal swabs, using QuantiNova Probe RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany) in a Light-Cycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) as described in detail elsewhere [40,41]. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Adult > 18 years old, and (2) ICU admission. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Negative RT-PCR result for COVID-19 in two consecutive samples taken 48 h apart, (2) patients that were transferred to other COVID-19 designated hospitals based on our Ministry of Health (MOH) surge plan, and (3) Health care workers with nosocomial acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The primary end-point was to investigate risk factors affecting 28-day mortality post-ICU admission. Usual outcome measures such as duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital length of stay were integrated in the analysis. The study was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Data Collection and Therapeutic Strategies

COVID-19 patient data recorded in health care records included routine demographic data, medical history, epidemiological exposure, comorbidities, symptoms, signs, laboratory results, coinfections and bacterial cultures results, chest X-rays and Computed Tomographic (CT) scans, applied therapies (i.e., antiviral therapy, corticosteroids, rescue invasive therapies, supportive ICU care), in-hospital complications, and clinical outcomes, were retrospectively analyzed. Pulmonary Embolism (PE) was confirmed by chest computed tomography angiography. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) was defined as per the “risk”, “injury”, and “failure” criteria [42]; while Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) was performed as per the kidney disease improving global outcomes 2019 guidelines when deemed to be necessary (i.e., anuria, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia) [43]. Interventional extracorporeal rescue therapies were performed according to pertinent ICU protocols. For example, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) was applied on patients with refractory hypoxemia [fraction of peripheral oxygen saturation to inspired oxygen saturation (PaO2/FiO2 ratio) < 80 for more than 6 h] based on available resources and practice recommendations [44]. Moreover, several critically ill patients with life-threatening COVID-19 and associated cytokine release syndrome were enrolled in our study regarding the administration of rescue Therapeutic Plasma Exchange (TPE) [45,46]. Upon ICU admission, we administered to all critically ill COVID-19 patients baseline therapy integrating ARDS-net and prone positioning ventilation, empiric antiviral treatment with ribavirin, and interferon beta-1b, as well as antibiotics, corticosteroids, anticoagulation, and other ICU supportive care as per individual clinical case scenario, and according to the Saudi MOH therapeutic protocol [47]. Admission Sequential Organ Function Assessment (SOFA) score, ICU Length of Stay (LOS), hospital LOS, clinical and paraclinical data were registered in all cases. All data were stored in electronic format and retrospectively analyzed.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

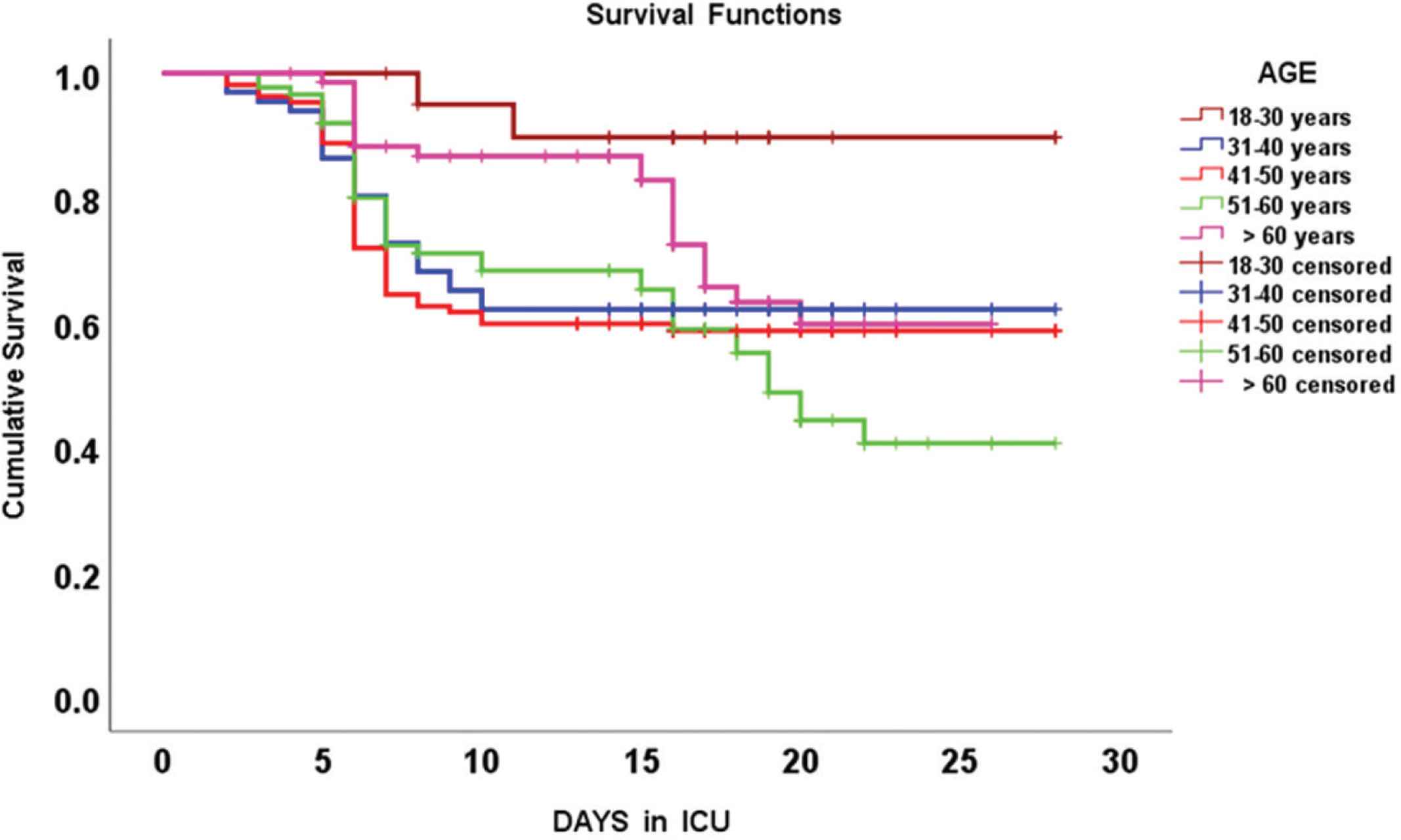

Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers or percentages. Continuous parameters are expressed as mean values ± Standard Deviation (SD) or median values with Interquartile Range (IQR) depending on their distribution. Differences of the studied parameters between survivors and non-survivors COVID-19 patients were evaluated by Wilcoxon Rank sum test for non-parametric data, and the student’s t-test for parametric data as appropriate. Logistic regression was used for each studied parameter over the binary outcome (survival/death) in univariate analysis. The significant predictors for 28-day mortality (p < 0.1) were used for multivariate regression modeling integrating Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). The forward stepwise method was adopted and tested for its goodness of fit by Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Survival analysis was visually presented by Kaplan-Meier curves, while the log-rank test was used to confirm the significance of probability trends for different age groups of COVID-19 patients. All tests were two tailed and considered significant when p-value <0.05. All data were analyzed using Stata/IC (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. RESULTS

The study flowchart is illustrated in Figure 1. Out of 436 critically ill patients with COVID-19, 352 were included in the final analysis. Eighty four patients were excluded due to transfer to other COVID-19 designated hospitals. Of the 352 mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients that were retrospectively analyzed, 239 survived (67.9%) and 113 patients (32.1%) expired. The main characteristics, clinical parameters, and outcome measures of COVID-19 critically ill patients are presented in Table 1.

Study flowchart.

| Parameters | Total patients (n = 352) | Survivors (n = 239) | Non-survivors (n = 113) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 50.63 ± 13.3 | 49.5 ± 13.1 | 53.1 ± 13.5 | 0.02* |

| Sex (Male: n, %) | 307 (87.2) | 207 (86.6) | 100 (88.5) | 0.6 |

| Nationality (non-Saudis: n, %) | 312(88.6) | 205 (85.8) | 107 (94.7) | 0.014* |

| Height (m) | 1.71 ± 0.6 | 1.71 ± 0.05 | 1.71 ± 0.07 | 0.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.5 ± 10.9 | 82.1 ± 11.6 | 83.2 ± 9.2 | 0.2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.2 ± 4 | 27 ± 4 | 28.7 ± 3.9 | 0.1 |

| Active smoker (n, %) | 174 (49.4) | 109 (45.6) | 65 (57.5) | 0.039* |

| Clinical parameters | ||||

| Respiratory rate (cycles/min) | 37.6 ± 2.9 | 37.6 ± 3 | 37.6 ± 2.7 | 0.99 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 99.8 ± 12.3 | 98.4 ± 12.2 | 102.7 ± 11.8 | 0.002* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 132.1 ± 20.3 | 132.7 ± 20.1 | 130.9 ± 20.7 | 0.4 |

| SOFA score upon ICU admission | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 0.04* |

| Comorbidities (n, %) | ||||

| No comorbidities | 71 (20.1) | 51 (21.3) | 20 (17.7) | 0.5 |

| One comorbidity | 92 (26.1) | 66 (27.6) | 26 (23) | 0.4 |

| Two or more comorbidities | 189 (53.6) | 122 (51.1) | 67 (59.3) | 0.2 |

| Prior to hospital admission symptoms | ||||

| Cough (n, %) | 336 (95.5) | 227 (95) | 109 (96.5) | 0.7 |

| Fever >38°C (n, %) | 220 (62.5) | 145 (60.7) | 75 (66.4) | 0.4 |

| Shortness of breath (n, %) | 316 (89.8) | 216 (90.4) | 100 (88.5) | 0.7 |

| Myalgia (n, %) | 156 (44.3) | 107 (44.8) | 49 (43.4) | 0.9 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl,12–17) | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 12.6 ± 0.4 | 0.003* |

| Creatinine (mg/dl, normal: 0.6–1.2) | 1 ± 0.27 | 1 ± 0.25 | 1.1 ± 0.29 | 0.3 |

| Lactate (mmol/l, normal: 1.0–2.5) | 1.81 ± 0.4 | 1.61 ± 0.33 | 2.13 ± 0.34 | 0.0001* |

| INR (normal: 0.8–1.2) | 1.2 ± 0.05 | 1.21 ± 0.049 | 1.19 ± 0.051 | 0.049* |

| White blood cells (cells/mm3, normal: 4–10) | 20.1 ± 3.5 | 20.1 ± 3.6 | 22.2 ± 2.7 | 0.0001* |

| Lymphocytes (109/l, normal: 1.1–3.2) | 0.8 ± 4.1 | 0.8 ± 3.1 | 0.6 ± 2.2 | 0.0001* |

| Platelets (cells/mm3, normal: 150–450) | 226.6 ± 74 | 231.3 ± 86.6 | 216.6 ± 31.3 | 0.07 |

| |

2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.33 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 0.0001* |

| ALT (μ/l, normal: 9–50) | 28.4 ± 7.9 | 28.8 ± 7.9 | 27.5 ± 7.7 | 0.15 |

| AST (μ/l, normal range 15–40) | 28.5 ± 11.1 | 28.1 ± 11.1 | 29.5 ± 11.1 | 0.24 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/l, normal: 0–26) | 15.1 ± 6.9 | 13.3 ± 4 | 13.9 ± 4.1 | 0.25 |

| Albumin (g/l, normal: 35–50) | 25.4 ± 3.9 | 25.3 ± 3.9 | 25.5 ± 3.9 | 0.62 |

| Ventilation parameters | ||||

| Intubated upon ICU admission (n, %) | 200 (56.8) | 114 (47.7) | 86 (76.1) | 0.001* |

| Positive-end-expiratory-pressure (cm·H2O) | 11.5 ± 2.5 | 11.6 ± 2.6 | 12 ± 2.4 | 0.63 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio | 157.9 ± 32.1 | 164.1 ± 33.9 | 144.7 ± 23.1 | 0.0001* |

| Outcome measures | ||||

| Symptoms onset to admission (days, IQR) | 9 (7–10) | 9 (7–10) | 8 (6–10) | 0.72 |

| Days on mechanical ventilation | 16 (8–28) | 15 (8–29) | 16 (9–30) | 0.55 |

| ICU length of stay (days, IQR) | 18 (9–29) | 16 (9–30) | 20 (11–33) | 0.046* |

| Hospital length of stay (days, IQR) | 20 (11–31) | 22 (11–32) | 23 (12–39) | 0.3 |

Parametric data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and non-parametric data are presented as median with IQR;

p < 0.05 were statistically significant.

INR, international normalization ratio; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SpO2/FiO2, saturation of peripheral oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen.

Main parameters and outcome measures of COVID-19 critically ill patients who survived (n = 239) or expired (n = 113)

The majority of critically ill patients with COVID-19 were males (87.2%) of non-Saudi nationality (88.6%). Prior to hospital admission their most common symptoms were cough (96%) and shortness of breath (90%). Most patients had ABO blood group type O+ (47%), followed by A+ (24%), and B+ (17%) types, respectively. One hundred and eighty-three patients (53.6%) had two or more comorbidities. The most usual comorbidities were hypertension (51.1%) and diabetes mellitus (27.6%). Chest CT scans were performed in 51.1% of cases, and showed bilateral ground-glass opacities with variable pulmonary parenchymal consolidations, which were consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia. No co-infections with other endemic viruses such as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), or influenza A and B viruses were recorded. However, 25 out of the 352 patients (7.1%) had nosocomial acquired bacterial infections: 15 patients had ventilator associated pneumonia, and ten patients had central-line associated infections. The most common isolated pathogens were: Acinetobacter baumannii, and methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus. Upon ICU admission, 200 out of the total enrolled patients (56.8%) were intubated and mechanically ventilated (Table 1). The 152 non-intubated patients received a higher level of oxygen support therapies: 100 patients via high flow nasal cannula, 20 via helmet-continuous-positive-airway-pressure, and 35 via Venturi masks. However, approximately 5 days (IQR: 2–7 days) post-ICU admission all patients were mechanically ventilated (100%).

Non-survivors were more frequently active smokers, and had higher SOFA scores on ICU admission, increased lactate, and

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, eight variables had significant effect on 28-day mortality. These variables were: age, ICU length of stay, SpO2/FiO2 ratio, white blood cells and lymphocytes counts,

| Parameters | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 1.06 (1.01–1.09) | 0.020* | 1.15 (1.03–1.21) | 0.022* |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 1.07 (1.03–1.14) | 0.001* | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 0.069 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio | 0.93 (0.82–0.97) | 0.001* | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.009* |

| White blood cells (109/l) | 1.20 (1.14–1.33) | 0.001* | 1.26 (1.06–1.51) | 0.061 |

| Lymphocytes (109/l) | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) | 0.001* | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) | 0.052 |

| 2.20 (1.70–2.70) | 0.001* | 2.54 (1.57–3.12) | 0.011* | |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 3.1 (2.2–4.7) | 0.001* | 3.9 (2.4–4.9) | 0.035* |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2.80 (1.92–3.31) | 0.003* | 2.91 (2.65–3.36) | 0.019* |

| Active smoking | 2.6 (2.03–3.50) | 0.037* | 3.00 (2.51–3.66) | 0.025* |

p < 0.05 were statistically significant.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models for 28-day mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19

Kaplan-Meier survival curves integrating different age groups of COVID-19 patients that were hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU).

| Age group in years | Mean survival time (days) (mean ± standard error) | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| 18–30 | 26.1 ± 1.2 | 23.6–28.6 |

| 31–40 | 19.7 ± 1.3 | 17.2–22.3 |

| 41–50 | 19.0 ± 1.1 | 16.9–21.1 |

| 51–60 | 18.4 ± 1.1 | 16.3–20.6 |

| >60 | 20.8 ± 0.92 | 19.1–22.6 |

| Overall | 20.0 ± 0.03 | 18.9–21.1 |

Mean survival time (days) post intensive care unit admission, in different age groups of COVID-19 critically ill patients

4. DISCUSSION

The main findings of this retrospective study can be summarized as follows. We found that old age, presence of PE, and increased lactate and

The presence of comorbidities and old age are poor prognostic indicators in hospitalized COVID-19 patients [4,9–11,16–19,31,32,34–39]. We found higher mortality rates in elderly patients; however, middle aged patients (41–50 years old) had also relatively high rates [4]. The mean age of our critically ill COVID-19 patients was younger compared to other studies [1–4,10,29–39]. This may be partially explained by the fact that the mean age of the general population in our country is relatively lower (≥65 years is <3%); compared to Asian, European, and American countries that were affected by the pandemic. Another possible explanation is that SARS-CoV-2 can also affect younger individuals with detrimental results [4,10,29–39]. These patients may present with severe extra-pulmonary manifestations such as brain infarctions [52]. In our study, although the incidence of stroke was higher in non-survivors, these were mainly elderly patients with other comorbidities. Moreover, we could not perform a detailed analysis of the neurological findings due to incomplete brain imaging information that were available during the study period.

Data from the UK and North America showed that black patients with COVID-19 had increased odds of death [53,54]. In our study, most patients were of Asian and Middle Eastern ethnic origin, and the vast majority was of non-Saudi nationality. We found that the majority of patients had ABO blood group type O+ (47%), but no correlation of ABO blood group type with mortality existed as it was previously suggested [55–57]. The incidence of hospital acquired bacterial infections, which was observed in this retrospective series, was comparable to other reports [25–39]. We did not find any co-infections with other endemic viruses such as MERS-CoV, which is in accordance with a previous Saudi Arabia based study [58]. Notwithstanding, the putative benefit from past exposure to MERS-CoV cannot be definitely excluded since a 50% genomic similarity between these two beta-coronaviruses exists. Also, we found that active smoking was a predictor of mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Anecdotal reports advocated that smoking was partially protective for COVID-19 in the beginning of the pandemic [59–61]. However, our results further confirmed recent studies that smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have increased odds of poor outcome when infected by SARS-CoV-2 [16,17,28,29,62,63].

This study has inherent limitations mainly due to its retrospective, single-center design. Also, the effect of applied interventional extracorporeal therapies such as ECMO or TPE on survival was not studied as this was not an end-point of the study. The latter was focused mainly on analyzing routine epidemiologic and clinical data of critically ill COVID-19 patients. In contrast to previous reports, we did not exclude critically ill patients that expired within the first 48 h after ICU admission as we wished to include the effect of fulminant COVID-19 and/or the occurrence of severe post-admission complications in our analysis [9,39]. Also, other clinical and paraclinical data such as mechanical ventilation parameters, detailed laboratory and imaging data were not available in all cases, which prevented a more meaningful subgroup analysis. The 28-day post-ICU admission mortality rate was 32.1%, which is relatively lower compared to initial reports in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients from China, Europe, and the US [4,9–11,16,37–39]. Notably, AKI that was previously identified as an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients did not emerge as a factor influencing mortality in our study [27–32,34–39]. We are uncertain whether this might be explained by the prompt application of interventional therapies such as CRRT or it could be attributed to the clinical notion that COVID-19 may not necessarily result in AKI [33]. Despite the aforementioned limitations, we found that old age, decreased SpO2/FiO2 ratio, and increased lactate, and

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Given his role as Editor in Chief, Ziad Memish had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to any information regarding its peer-review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Dr. Shahul Ebrahim. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AA contributed in idea, concept, proposal, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval. WA contributed in idea, concept, proposal, data collection, data entry, data analysis, manuscript writing, and final approval. FF, AB, FA, KA, PJ and HT contributed in idea, concept, proposal, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, and final approval. SAA and DK contributed in data interpretation, manuscript writing, critical reviewing, and final approval. ZAM contributed in idea, concept, data interpretation, manuscript writing, critical reviewing, and final approval.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Abdulrahman Alharthy AU - Waleed Aletreby AU - Fahad Faqihi AU - Abdullah Balhamar AU - Feisal Alaklobi AU - Khaled Alanezi AU - Parameaswari Jaganathan AU - Hani Tamim AU - Saleh A Alqahtani AU - Dimitrios Karakitsos AU - Ziad A Memish PY - 2020 DA - 2020/10/03 TI - Clinical Characteristics and Predictors of 28-Day Mortality in 352 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Study JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 98 EP - 104 VL - 11 IS - 1 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200928.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.200928.001 ID - Alharthy2020 ER -