An Evaluation of Health Policy Implementation for Hajj Pilgrims in Indonesia

- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.200411.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Hajj pilgrims; health isthitaah; policy implementation

- Abstract

Background: For last decades, the mortality rate of hajj pilgrims from Indonesia was between 2.1 and 3.2 per 1000 hajj pilgrims. At the same time, morbidity affected 87% of the elderly (>65 years old), of which 83% faced high risk of health problems. This is a complex problem affecting hajj health care in Indonesia. The study was aimed to understand what extent of the hajj implementation on health care in Indonesia.

Methods: This review was conducted by abstracting of three studies in Indonesian hajj health care. Two of the studies were based on cross-sectional reviews, while one was a case–control study. The majority of the studies performed laboratory tests to evaluate the disease conditions among hajj pilgrims through secondary data.

Results: First study presented that hajj Posbindu (integrated post-coaching) was not functional in managing the health problems of the pilgrims. It shows that the stroke prevalence is 10.9 per 1000 people, Diabetes Mellitus (DM) 10.9% of the people, and coronary heart disease 1.5%. The second study expressed that, according to health isthitaah (policy implementation), there were 20% hajj pilgrims who delayed their trip because of health issues. Most of them had chronic kidney disease, dementia, or lung tuberculosis. The policy implementation of health isthitaah was not smooth; there was little collaboration between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Religious Affairs, and the population was not sufficiently educated in the area, resulting in hajj pilgrims with poor knowledge, attitude, and practice in health isthitaah. This notion was enforced in the third study.

Conclusion: The coaching according to health isthitaah should be encouraged alongside collaboration between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Religious Affairs. Socialization in public health has to increase according to health isthitaah, which can be done by district health centers.

- Copyright

- © 2020 The Authors. Published by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

For last decades, the mortality rate of hajj pilgrims from Indonesia was 2.1–3.2 per 1000 hajj pilgrims [1], which is three times more compared with general population. In 2017, the total of hajj pilgrims from the country was 221,000 persons. Most of them were elderly, with high risk of health issues and mortality. Some of the most common issues were cardiovascular disease, respiratory infections, chronic obstructive lung disease, Diabetes Mellitus (DM), hypertension, stroke, urogenital infection, psychiatric disorders, and cancer [2].

In 2013, 87% of hajj pilgrims were elderly (>65 years old), of which 83% faced high risk of health problems [2,3]. According to Saudi Arabia’s morbidity data, 42.4% had hypertension, 14.9% DM, 13.9% metabolic syndrome and hyperlipidemia, and 6.8% cardiomegaly [4]. In Indonesia, mortality data shows that 50% of deaths were caused by cardiovascular factors and stroke, 27.5% by lung disease, and 13% by infectious illnesses [5,6].

Hajj health in Indonesia is a complex problem. According to the 2012–2014 audit results on current hajj management, many hajj pilgrims who did not follow the health isthitaah still went on to perform hajj, and hajj pilgrim who required hemodialysis were allowed to go to Saudi Arabia even with the lack of professional health care resources. On the other hand, data in 2015 shows that two cases of death among hajj pilgrims were suspected to have no health isthitaah [7]. Although isthitaah is the term that should be described by three aspects of hajj process requirements for the hajj pilgrims including faith, wealth, and physical; however, it is most frequently referring the sufficient physical and health capability condition that was required by the hajj pilgrims to follow all hajj process with safe and comfort.

To date, there were no solutions to the widespread problems of hajj health care. Surveillance of the hajj pilgrims’ health experienced multifaceted obstacles on three phases of stages which is comprised of departure, implementation, and arrival of all hajj process. To address the issue, Pusat Kesehatan Haji (Hajj Health Center, Indonesian Ministry of Health) developed JIHAT card, meaning “healthy hajj”. The aim of this study was to create a system that could monitor and evaluate hajj pilgrims in comprehensive and integrated ways [8], thus providing more qualified and professional hajj health care [9].

Rule No. 15 of the Ministry of Health in Indonesia (2016) explains the three steps of health examination in hajj health care. First is primary health care in one’s district, second is medical checkup at a hospital in one’s district region, and the third is checking (most of them in the province, or other areas) that the hajj pilgrim is fit to fly before embarking on the journey to Saudi Arabia [10]. The rules also explain health isthitaah (meaning the health status of hajj pilgrims meets the minimum standards) [11].

Because of the long duration between departure for hajj and payment of hajj expenses, there is time for coaching of health isthitaah through medical checkup, rites hajj training, promotion, and preventive measures, especially in the utility of post-integrated coaching in non-communicable diseases (Posbindu PTM), training in physical activity, etc. [12]. At first, Posbindu PTM is the concept to implement and maintain good life by routine physical exercise, stress management, and healthy lifestyle at the largest community regarding to Indonesian Ministry of Health guideline for non-communicable disease namely Gerakan Masyarakat Hidup Sehat – GERMAS (Community Healthy Life Movement) [13]. Latest, Posbindu PTM concept seems positively to being concern for the hajj pilgrims’ pre-departure health care [12]. However, it is not well implemented as the medical therapy and treatment is more likely as the main health care paradigm rather than promotive and preventive care in Indonesia [14–16], including in hajj health care.

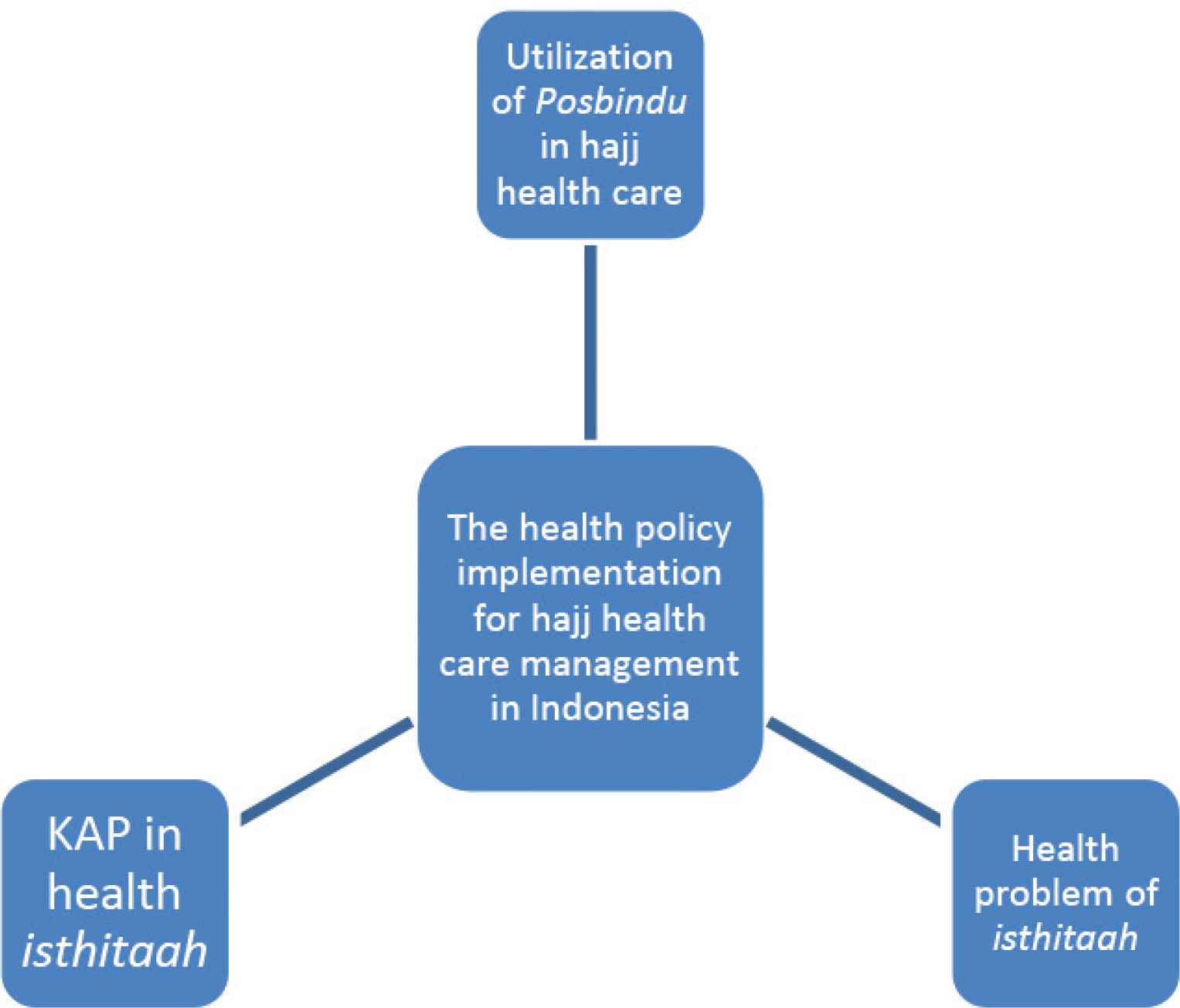

Hajj problem in health care is complicated and need extra effort to solve it. This study is the abstraction of three studies in hajj health care that we have done, as shown in Figure 1. This study is aimed to understand what extent of the hajj implementation on health care in Indonesia.

The abstraction of this study from three studies in the health care management of hajj pilgrims.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Research Setting

Six major embarkations of Indonesian provinces comprised of Jawa Barat, Jawa Tengah, Jawa Timur, Sulawesi Selatan, Kalimantan Selatan, and Sumatera Barat. Indonesia is a country located in South-East Asia with the biggest Moslem citizen country in the world.

2.2. Data Procedure

The study was initiated in September 2019 and approved in early October 2019. The duration was 3 months, from mid-October to December 2019. The data procedure for this study consists of the following: (a) identifying the data from the first study that presented the utility of Posbindu PTM in coaching hajj pilgrims, (b) specifying the health policy research at the second study, and (c) exploring on knowledge, attitude and practice at the third study. All these procedures were held subsequently from each participants’ studies.

2.3. Data Source

This work was conducted by abstracting of three studies in Indonesian hajj health care that we have done. The first study of 2017 analyzed the utility of Posbindu PTM in coaching hajj pilgrims in six provinces, the second study of 2018 was a health policy research in health isthitaah during embarkation (national data of Indonesia), and the third study of 2019 was on knowledge, attitude and practice in health isthitaah.

All these studies were published as the report working paper that can be only having by formal data request procedure to Data Management Office of The National Institute for Health Research and Development, The Indonesian Ministry of Health (Laboratorium Manajemen Data Balitbangkes RI): Jl. Percetakan Negara No. 29, Jakarta, Indonesia 10560, Phone: (+62-21) 4261088. These studies were funded by The Center for Health Hajj and The National Institute for Health Research and Development, The Indonesian Ministry of Health.

2.4. Instrument and Data Analysis

In majority of the studies, laboratory tests were performed to evaluate the disease conditions among hajj pilgrims. Various kinds of instruments were used in the quantitative studies and some in the qualitative studies. The quantitative data having by valid and reliable questionnaires were used to measure the demographic data in selected participants of these studies, while calibrated microtoise and stature meter measured the body and height scales as Body Mass Index (BMI) index. Besides participants were having blood sample test, they also were having systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurement by calibrated sphygmomanometer.

The qualitative data were measured by focus group discussion (FGD) and depth-interview to stakeholders include hajj task force team that was formed by each regional which consisted of regional health office, regional office of ministry of religion, primary and secondary health care facilities. Meanwhile, checklist observation in qualitative guideline was also used to capture the related legal data and information of each studies objectives.

Regarding the study design of the selected pieces of research, two of the studies were based on cross-sectional studies, while the last one was a case–control study. SPSS statistical software that was licensed by the Faculty of Public Health - Universitas Indonesia was used to run the frequency distribution analysis which presented the data proportion of data, and carried on with Chi-square (χ2) analysis in exploring the categorical data relationship between the variables. Meanwhile, the content analysis produced and managed the main findings from the qualitative data of FGD and depth-interview.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows that the variable for education, occupation, economic status, and insurance was significant (p < 0.05) compared with the intervention and control groups. The percentages of men and women were almost equal. Most of the hajj pilgrims fell in the 46–65 age group.

| Variables | Intervention | Control | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | ||

| Sex | 0.203 | ||||

| Men | 76 | 50.7 | 65 | 43.3 | |

| Women | 74 | 49.3 | 85 | 56.7 | |

| Age group (years) | 0.202 | ||||

| <25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.7 | |

| 25–45 | 46 | 30.7 | 32 | 27.6 | |

| 46–65 | 60 | 60.0 | 76 | 65.5 | |

| >65 | 93 | 9.3 | 6 | 5.2 | |

| Education | 0 | ||||

| Low | 24 | 16.0 | 35 | 23.3 | |

| Middle | 67 | 44.7 | 87 | 58.0 | |

| High | 59 | 39.3 | 28 | 18.7 | |

| Occupation | 0.026 | ||||

| Unemployed | 2 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Housewife | 48 | 32.0 | 54 | 36.0 | |

| Govt. employee | 13 | 8.7 | 10 | 6.7 | |

| Private employee | 32 | 21.3 | 12 | 8.0 | |

| Entrepreneur | 33 | 22.0 | 51 | 34.0 | |

| Pensioner | 17 | 11.3 | 14 | 9.3 | |

| Others | 5 | 3.3 | 7 | 4.7 | |

| Economic status | 0.009 | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 19 | 12.7 | 11 | 7.3 | |

| Quintile 2 | 82 | 54.7 | 94 | 62.7 | |

| Quintile 3 | 23 | 15.3 | 35 | 23.3 | |

| Quintile 4 | 8 | 5.3 | 5 | 3.3 | |

| Quintile 5 | 18 | 12 | 5 | 3.3 | |

| Have insurance | 0 | ||||

| Yes | 79 | 52.7 | 30 | 20.0 | |

| No | 71 | 47.3 | 120 | 80.0 | |

Characteristics of hajj pilgrims [17]

Table 2 shows the variables tested in Indonesia (pre-testing) before hajj pilgrims departed to Saudi Arabia. Testing was also done in Saudi Arabia (post-testing). The diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and blood glucose level generally did not change between pre- and post-testing (p < 0.05). The other variables, systolic blood pressure and BMI, were not consistent in pre- and post-testing.

| Variables | Pre-test | p-value | Post-test | p-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |||||||

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |||

| Systole | 0.734 | 0.026 | ||||||||

| <140 mm/Hg | 139 | 92.7 | 108 | 72.0 | 134 | 89.3 | 107 | 71.3 | ||

| ≥140 mm Hg | 11 | 7.3 | 42 | 28.0 | 16 | 10.7 | 43 | 28.7 | ||

| Diastole | 0.027 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| <90 mm Hg | 105 | 70.0 | 97 | 64.7 | 108 | 72.0 | 95 | 63.3 | ||

| ≥90 mm Hg | 45 | 30.0 | 53 | 35.3 | 42 | 28.0 | 55 | 36.7 | ||

| BMI | 0.014 | 0.106 | ||||||||

| Slim | 8 | 5.3 | 7 | 4.7 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 4.7 | ||

| Normal | 69 | 46 | 102 | 68 | 60 | 40 | 71 | 47.3 | ||

| Overweight | 36 | 24 | 27 | 18 | 34 | 22.7 | 41 | 27.3 | ||

| Obese | 37 | 24.7 | 16 | 10.7 | 50 | 33.3 | 31 | 20.7 | ||

| Total cholesterol | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Normal | 135 | 90 | 141 | 94.0 | 150 | 100 | 150 | 100 | ||

| High | 15 | 10 | 9 | 6.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Blood glucose | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Normal | 134 | 89.3 | 143 | 95.3 | 150 | 100 | 150 | 100 | ||

| High | 16 | 10.7 | 7 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Health problems of hajj pilgrims [17]

The evaluation of health isthitaah shows that the number of hajj pilgrims who delayed their trip to Saudi Arabia, according to isthitaah’s criteria in 2016, was about 118 persons—64 men and 54 women, most of them in the >65 years age group. The profile of the diseases is shown in Table 3.

| No. | Diseases | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chronic kidney disease | 33 (35.1) |

| 2 | Dementia | 11 (11.7) |

| 3 | Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) | 7 (7.4) |

| 4 | Type 2 DM | 6 (6.4) |

| 5 | Essential hypertension | 6 (6.4) |

| 6 | Senility | 5 (5.3) |

| 7 | Heart failure | 4 (4.3) |

| 8 | Cancer | 4 (4.3) |

| 9 | Fracture | 2 (2.1) |

| 10 | Parkinson’s disease | 2 (2.1) |

| 11 | Acute psychosis | 2 (2.1) |

| 12 | Schizophrenia | 2 (2.1) |

| 13 | Stroke | 1 (1.1) |

| 14 | Acute kidney injury | 1 (1.1) |

| 15 | Ascites | 1 (1.1) |

| 16 | Hypertensive heart disease | 1 (1.1) |

| 17 | Chronic ischemic heart disease | 1 (1.1) |

| 18 | Cardiomegaly | 1 (1.1) |

| 19 | Melena | 1 (1.1) |

| 20 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (1.1) |

| 21 | Hepatitis | 1 (1.1) |

| 22 | Varicella | 1 (1.1) |

Hajj pilgrims who delayed their trip to Saudi Arabia [18]

3.1. Disease Pattern of Hajj Pilgrims Encountering Delay (According to isthitaah)

Chronic kidney disease was the most frequently reported disease (35.1%), followed by dementia (11.7%), and pulmonary tuberculosis (7.4%).

3.2. Policy for Hajj Pilgrims

At the time of writing, the implementation of Rule No. 15 of the Ministry of Health in Indonesia (2016) about health isthitaah is ongoing. This rule aims to manage the medical examination system of hajj pilgrims in Indonesia. There are three steps involved in this system [9]:

- (a)

The first step involves primary health care for hajj pilgrims in their domicile, to determine whether a person is a health risk or not.

- (b)

The second step is carried out in the hospital to determine whether the hajj pilgrim needs assistance (be it a person or drugs, according to one’s disease) or is fit to go independently.

- (c)

The third step is embarkation, to determine whether the hajj pilgrim is fit to fly to Saudi Arabia or not.

A pilgrim will be provided with assistance if he/she is 60 years old or above and has a disease, not including the list in Rule No. 15 (2016). A hajj pilgrim who does not meet the temporary requirements is an individual who [19]:

- (a)

Does not have international vaccination.

- (b)

Has one or more of the following diseases: lung TB with positive BTA, MDR lung TB, uncontrolled DM, hyperthyroid, HIV/AIDS with chronic diarrhea, acute stroke, and anemia.

- (c)

Is suspected or confirmed to have an epidemic disease.

- (d)

Has acute psychosis.

- (e)

Has fracture or back pain without neurological complication.

- (f)

Is pregnant <14 weeks or >26 weeks.

Meanwhile, a hajj pilgrim who does not meet the requirement of isthitaah is someone who has [20]:

- (a)

A chronic disease (stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stage 4 chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis, stage 4 AIDS with infections, hemorrhagic stroke).

- (b)

Schizophrenia, dementia, and mental retardation.

- (c)

Stage 4 cancer, totally drug-resistant (TDR) lung TB, cirrhosis, and decompensated hepatitis.

3.3. Policy Implementation Gap of Health Isthitaah

In the system of medical checks for hajj pilgrims in Indonesia, there needs to be coordination between the primary health care, hospital, and embarkation stages. In primary health care, the hajj pilgrims undergo a medical examination to get a diagnosis of their health status, before going to the hospital to undergo referral examination for a more complete profile of their health status. At the embarkation stage, hajj pilgrims only need to undergo screening to confirm that they are fit to fly.

It is important to standardize diagnosis in health isthitaah and socialization of health workers in primary health care. One of the things that could be done was to hold a workshop for health workers in each province (there are 34 provinces in Indonesia). The isthitaah’s criteria were not only in medical diagnosis but functional diagnosis too. Of all hajj pilgrims whose trip to Saudi Arabia was delayed, there were 20% who could go, if the technical criteria were enforced.

Hajj pilgrims with high health risk should be coached 6 months before departure. It is hoped that coaching could repair the health status of hajj pilgrims. The coaching is a collaboration between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Religious Affairs in manasic training. For example, sports that suit the health conditions of hajj pilgrims can be introduced, such as low-impact aerobic gymnastics (at 60% of maximum heart rate) for healthy hajj pilgrims. It appears that medical examination of health isthitaah should be held a year before departure, not in the year of departure to Saudi Arabia.

3.4. The Result of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice in Health Isthitaah

Table 4 consists of composite criteria in health isthitaah according to the knowledge, attitude, and practice of hajj pilgrims. Only the attitude variable scores mostly “good”.

| Scale | Knowledge (%) | Attitude (%) | Practice (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | 32.5 | 86.8 | 55 |

| Middle | 37.2 | 12.8 | 43.8 |

| Bad | 30 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

Scales of knowledge, attitude, and practice in health isthitaah [21]

The dominant variables in the last model of multivariate analysis that were connected to the practice of health isthitaah were knowledge, attitude, and waiting time (Table 5). The odds ratio (OR) was knowledge with 2.7 times (95% CI 1.081–2.839, and p = 0.021).

| Variables | β | p-value | Exponent (β) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Knowledge | 0.524 | 0.021 | 2.689 | 1.081 | 2.839 |

| Attitude | 0.103 | 0.035 | 1.108 | 1.007 | 1.219 |

| Waiting time | −0.634 | 0.000 | 0.530 | 0.379 | 0.688 |

| Constant | 2.121 | 0.087 | 6.571 | – | – |

Multivariate of correlation between knowledge, attitude, and waiting time in the practice of health isthitaah in Indonesia [21]

4. DISCUSSION

This brief work intends to provide an analysis of three studies on the pattern of health problems over 5 years with regards to hajj pilgrims in Indonesia. This part discusses the outcomes of the study on policy implementation of health isthitaah for pilgrims during pilgrimage and suggestions for future investigation. In the first study, we could see that hajj Posbindu (integrated post-coaching) was not functional in managing the health problems of the pilgrims. Table 1 showed the profile of hajj pilgrims in Indonesia, who were mostly women aged 46 and above, held the occupation housewife or entrepreneur, and were in the second quintile of the socioeconomic status. In Table 2, we saw that hypertension was a big problem. It shows that the rate of hypertension as diagnosed by medical doctors was 8.4%, but 34.1% by measuring systole and diastole. Additionally, stroke affected 10.9 per 1000 people, DM 10.9% of the people, and coronary heart disease 1.5% [22].

The second study expressed that, according to health isthitaah (policy implementation), there were 20% hajj pilgrims who delayed their trip because of health issues. Most of them had chronic kidney disease, dementia, or lung TB. It shows that chronic kidney disease affected 19.3% of the pilgrims, making it a national health problem in Indonesia [11,17] while in the general population it occurred on two per 1000 which its most frequently affected to age of 75 years old (0.6%) which the prevalence at male (0.3%) higher than female (0.2%) [23,24]. The policy implementation of health isthitaah was not smooth; there was little collaboration between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Religious Affairs, and the population was not sufficiently educated in the area, resulting in hajj pilgrims with poor knowledge, attitude, and practice in health isthitaah. This notion was enforced in the third study. In the multivariate analysis, only knowledge correlated with practice in getting OR.

5. CONCLUSION

Posbindu (post-integrated coaching) was not functional in managing the health problems of hajj pilgrims in 2015. The implementation of health isthitaah in Indonesia in 2016 caused 20% of hajj pilgrims to delay their departure to Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Related to the health isthitaah policy, only the attitude variable scored mostly “good”. Dominant variables connected to the practice of health isthitaah were knowledge, attitude, and waiting time in the last model of multivariate analysis. The OR was knowledge at 2.7 times. Policy implementation in health isthitaah should improve, especially in the health area and among hajj pilgrims (the population). The results of the three studies found that coaching according to health isthitaah should be encouraged by empowering collaboration between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Religious Affairs. Public health awareness and education should increase according to health isthitaah, which can be done by district health centers.

This study provides an evaluation on Health Policy Implementation for Hajj pilgrims in Indonesia. Further study is needed that will present more specifically on Hajj pilgrimage that presents major public health and infection control challenges, especially for elderly who are exposed to fatigue and extreme weather conditions. In this context, it is important for national health agencies and those providing health care services to Hajj pilgrims to implement efficient strategies, before and during the pilgrimage, to increase awareness of the health hazards during the Hajj, and to improve health management of returning pilgrims from Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) to limit the spreading of infectious diseases that are very common during the Hajj.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

RR planned and conducted the study. AA wrote the first draft of the manuscript and analyzed the findings report. RO and TR were both involved in the critical revision of the report and manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by The National Institute for Health Research Development, Indonesian Ministry of Health. We are also thanks to The Indonesian Center for Health Hajj. The study conclusions are those of the authors and any views expressed are not necessarily those of the funding agency.

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Rustika Rustika AU - Ratih Oemiati AU - Al Asyary AU - Tety Rachmawati PY - 2020 DA - 2020/04/20 TI - An Evaluation of Health Policy Implementation for Hajj Pilgrims in Indonesia JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 263 EP - 268 VL - 10 IS - 4 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200411.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.200411.001 ID - Rustika2020 ER -