Proving Hegel Wrong: Learning the Right Lessons from European Integration for the African Continental Free Trade Area

- DOI

- 10.2991/jat.k.210908.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- AfCFTA; European Union; single market programme; deep integration

- Abstract

This paper sets out to disprove the German philosopher Hegel’s dictum about people learning nothing from history, by looking at the lessons to be learned for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) from the European Union’s experience of regional integration. Since its foundation in 1957, European integration has had a chequered history, with its fair share of triumphs and setbacks. This paper focuses on the evidence from economic studies and the lessons to be gleaned from the Single Market Programme (SMP), which was initiated in 1993 and ushered in the creation of a unified European market. The parallels are far from perfect: structurally, in the level of development and resources available to support regional integration, there are major differences between the SMP and the AfCFTA. Nevertheless, this paper highlights nine major lessons for the African continent from the SMP, including the scale of benefits to be expected, the role of multinational corporations, the need for an effective competition policy and the importance of public buy-in to the process.

- Copyright

- © 2021 African Export-Import Bank. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The German philosopher G.W.K. Hegel1 once famously said that “the only thing we learn from history is…that we learn nothing from history.” This is one of those dictums which—regrettably—all too often proves to be true. However, there is no need for this to be the case. In this paper, it is argued that, while accepting that there are limitations to such comparisons—major differences exist in terms of the respective starting points of the two projects—there are nonetheless important lessons to be gleaned for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) from the European Union (EU) experience. More specifically, this article will make a comparison between the European Single Market Programme (SMP), which came into force on 1 January 1993, and the AfCFTA, which entered its implementation stage on 1 January 2021.

Ever since independence, pan-African initiatives have been received with scepticism, both from within the continent and outside. For example, in a recent book on African economic development, Cramer et al. (2020:63–65) argue that

“The swell of support for South–South cooperation and initiatives such as the AfCFTA is partly based on a pessimistic view of possible integration into the wider world economy…while African regional economic integration and greater intra-African trade may be rhetorically appealing on grounds of economic nationalism or South–South solidarity, as a blueprint for accelerated development it is a fantasy—based on exactly the same theories and conditional assumptions as a push for global free trade on comparative advantage grounds.”

Conflating the name ‘Free Trade Area’ with another wave of Washington-inspired liberalization, criticisms have been also voiced that the AfCFTA is embracing a ‘neo-liberal agenda’ (e.g. Agbakwuru, 2019; Kombo, 2019). Hirschman (1963) once wrote about how Latin America was afflicted by ‘fracasomania’—the belief that domestic-led initiatives were doomed to failure; it would appear that the African continent is often similarly stricken by excessive negativism.

Yet criticisms of this nature reflect several key misunderstandings about what the AfCFTA is setting out to achieve. Despite its title, the AfCFTA is about much more than creating a free trade area—it is about building a framework for much deeper African regional integration and cooperation, with a view to making the continent economically stronger and more resilient (AU, 2018). It is about boosting the levels of industrialization, intraregional trade in both goods and services, and investment. In addition, the agreement contains safeguards, including protocols on competition policy, on investment, on Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) and on the free movement of people and business. In short, it is about creating a unified continental market that works to the benefit of its citizens (ECA, 2020).

It is undoubtedly a very ambitious agenda and, as such, its implementation needs to be well informed by both academic research and past precedent. A major precedent is the EU: since its inception in 1957, the EU has frequently served as a model for other regional organizations (Schiff and Winter, 2003; Molle, 2016; Lenz, 2018; Juma and Mangeni, 2018). Yet it too has had to contend with cynicism.2 A lot of the internal criticisms spring from genuine disagreements about how the EU project should proceed (James, 2016). For some reason, US-based economists issue particularly harsh judgments, with the project of monetary union being singled out for especially vehement criticism.3 The critical voices also cut across political divides, coming from both the political left and right (e.g. Feldstein, 2012; Krugman, 2015; Stiglitz 2020). Rodrik (2017), for instance, claims that

“Today, the [European] Union is mired in a deep existential crisis, and its future is very much in doubt. The symptoms are everywhere: Brexit, crushing levels of youth unemployment in Greece and Spain, debt and stagnation in Italy, the rise of populist movements, and a backlash against immigrants and the euro. They all point to the need for a major overhaul of Europe’s institutions.”

There is no denying that the EU project has suffered some severe setbacks—among them, the collapse of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992, the ‘Greek’ crisis of 2011 and, most recently, in 2016 the referendum of the UK to leave the EU. The institutions of the EU are also frequently accused of being in decline, as exemplified by slow decision-making and an excessive bureaucracy, although whether these arguments are sustainable has been contested (Nugent and Rhinard, 2016).

Yet what surprises many people is the resilience of the idea of a united Europe (Lenz, 2018). Broadly speaking, European citizens are still attached to many of the freedoms that the EU has bestowed. In a Pew Research (2019) poll held in 2018, a median of 74% of respondents still believe that the EU promotes peace, and most also think it promotes democratic values and prosperity.4 Arguably it is precisely because the European model of integration can simultaneously celebrate major achievements and needs to address some fundamental flaws that it makes such an interesting and informative case study. It is a flawed model, but not one without many redeeming features. As a case study on how to achieve regional integration, then, the EU represents an experience that is unparalleled and impossible to ignore. As a proposition, it contains many lessons for the AfCFTA, as the continent embarks on the crucial stage of implementation.

A word on the selection of papers for review. The studies in this paper in the main refer specifically to the Single Market period. Otherwise, the assessment would not compare like with like. Hence the author has tended to ignore excellent studies or reviews like that by Crafts (2016) or Badinger and Breuss (2004) that cover the period from 1960 to 2000, even although there is significant temporal overlap. In addition, the paper does not delve into the theory behind the empirical results, but the interested reader can find plenty of relevant literature.5

Some clarifications are also in order about the paper’s analytical scope. It is focused principally on the economic implications and implementation of the Single Market—beyond flagging the importance of popular support and understanding, it does not delve much into political dimensions. Yet those political dimensions are difficult to extricate from such discussions. Regional integration is inherently political, with countries deciding to cede a degree of national sovereignty in exchange for the economic and political benefits stemming from regional integration.6

There is also an emphasis on reviewing macroeconomic rather than microeconomic papers. There is undoubtedly a wealth of studies to draw upon. However, because of the vast volume of literature, this review has by necessity been selective, focusing generally on more recent studies rather than older studies, on the grounds both of more complete data and (presumably) better methodological approaches.7

2. PARALLELS WITH THE SINGLE MARKET PROGRAMME 1992

“Because of the success of the European Union, we are all compelled to unconsciously compare the African experience with the European experience. We read the European experience in a very teleological sense, in the sense that we assume that whatever happened in Europe since the Second World War was part and parcel of a deliberate process to build the Europe that we see today. We interpret every event in the past as if it was a necessary and well thought out activity that led to this integration of Europe.”

The SMP represented a major acceleration towards the European goal of achieving ‘ever-deeper regional integration’. Critics may argue that the differences between the two projects—the AfCFTA and SMP—are so vast that it renders any comparisons futile, but on reading the main provisions and associated protocols of the AfCFTA, the degree of overlap in terms of objectives is marked. Among the main provisions of the SMP were:

- •

the removal of border controls (and the attendant delays) for goods transported on land and water;

- •

the liberalization in the provision of services across borders (although the most important measures came later with the so-called Services Directive);

- •

the establishment of the principle of mutual recognition of national product regulations;

- •

the removal of controls on financial capital movements;

- •

the removed discriminatory rules on direct investment from other member states;

- •

established freedom to reside and work in other member states;

- •

and established a common competition policy (Flam, 2016).

The specific objectives of the AfCFTA, in turn, are spelled out in Article 4 of the agreement, whereby State Parties agree to:

- (a)

progressively eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods;

- (b)

progressively liberalize trade in services;

- (c)

cooperate on investment, intellectual property rights and competition policy;

- (d)

cooperate on all trade-related areas;

- (e)

cooperate on customs matters and the implementation of trade facilitation measures;

- (f)

establish a mechanism for the settlement of disputes concerning their rights and obligations; and

- (g)

establish and maintain an institutional framework for the implementation and administration of the AfCFTA (AU, 2018).

In fact, it could be argued that the most striking differences refer to the initial conditions rather than broad objectives of the two agreements:

- •

The Scale is Different: The EU project evolved gradually, starting with six members and gradually expanding its membership over the course of six decades. It is now a block of 27 member states and, despite the recent loss of the UK, still has intentions to expand its membership. The AfCFTA has 54 members signed up—exactly double the number of the EU. In terms of membership alone, this makes the AfCFTA the world’s largest regional block.8

- •

The Global Economy Has Changed: Since the European SMP was implemented in the 1990s, the global economy has, in many senses, changed beyond recognition, with the prevalence of global value-chains, the rise of China and India, the rapid emergence of the digital economy and the heightened importance of services (UNCTAD, 2013; Kaplinsky, 2021). The context is thus very different now, and economic policies that may have worked effectively during the implementation of the SMP may not prove equally effective with regard to the AfCFTA.9

- •

The Level of Economic Development Is Much Higher: Going into the SMP, the EU already had a higher level of income per capita, infrastructure and intraregional trade than that currently prevalent on the African continent. Resources matter for the successful implementation of any process of regional integration, and the EU has been blessed with enough financial resources to address the challenges that have inevitably arisen, through creating, inter alia, creating Structural and Cohesion Funds to deal with the problems of lagging regions. Africa, by contrast, confronts some major financial resource constraints, particularly in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

- •

Previously Established Customs Union: In one important economic aspect, Europe had the advantage that it had already established a customs union before embarking on the SMP. The ECC Customs Union was created in 1968 among the original six members of the then European Economic Community (EEC). For the AfCFTA, although the intention is to move toward the creation of a continental customs union, at present there is no fixed date for its implementation.

Some of these differences can be laboured, however. For instance, in the early stages of European integration, the so-called ‘peripheral’ European economies (Greece, Ireland, Spain, Portugal) exhibited many of the structural characteristics of ‘developing economies’, including low per capita incomes, poor infrastructure, low levels of industrialization, mass outward migration and major governance issues. One edited volume led by a renowned specialist, Dudley Seers (Seers, 1979) on development economics was entitled ‘Underdeveloped Europe: Studies in the European Periphery’.

Even accepting these caveats, this paper nevertheless argues that the European SMP is a helpful exemplar for the AfCFTA. The SMP had a profound impact on the process of EU integration. Not only did it produce a single market with a size close to the US economy, but it also created a situation whereby further integration became all but inevitable (Sapir, 2011). Embarked upon in 1986, and operative from 1 January 1993, SMP represented a major step forward for the EU project, in terms of deepening the Common Market to allow for the free movement of capital and people. The legislative parallels with the AfCFTA, in terms of the main objective of creating a single continental market for goods and services and the accompanying protocols on free movement, on competition, on investment and intellectual property, are summarized in Table 1.

| SMP | AfCFTA | |

|---|---|---|

| Merchandize trade | Full liberalization, Common External Tariff (CET) | ‘Substantially all trade’ liberalized, eventual establishment of CET |

| Services trade | Liberalized provision of cross-border services11 | Focuses initially on five priority sectors |

| Intellectual property | European Patent Office formed prior to the SMP (1977) | Under negotiation |

| Competition policy | Predates the SMP, but given greater powers subsequently | Under negotiation |

| Free movement | Fully established for core members, some constraints on new members | Under negotiation |

| Monetary union | Only countries signed up to Single Currency | Eventual objective |

| Financial resources | Structural Funds, Cohesion funds. Revenue generated by implementation of the CET and members’ contributions | Support currently limited to trade facilitation and limited BoP support under Afreximbank. Plans to boost the 2012 action plan for boosting Intra-African trade |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

The scale of ambition – comparing the EU SMP to the AfCFTA10

3. KEY LESSONS LEARNED

In this section of the paper, we will review retrospective empirical studies into the impact of the SMP. These studies provide a guide to the ballpark gains accruable from the implementation AfCFTA, as well as providing some methodological warnings into the complexity of assessing potential gains from any regional integration process. The section will also cover reviews of several major institutional and policy issues which will, in the opinion of this author, require attention if the AfCFTA is to be implemented effectively.

3.1. Lesson #1: Measuring the Welfare Gains from ‘Deep Regional Integration’ is Complex…

“The overall economic verdict is cautiously favourable. Integration has clearly not been a panacea for the Continent’s economic ills, as claimed by some of its proponents. But it has bestowed some benefits.”

Regional integration is one of those thorny subjects among economists whereby the benefits are often exaggerated by their proponents and minimized by their detractors. For the non-economist, it can be a minefield to negotiate one’s way through the vast body of literature. Stressing a belief that ‘trade diversion’ will usually outweigh ‘trade creation’ (Viner, 1950), a minority of economists (e.g. Panagariya, 1998; Bhagwati, 2002) even argue that regional integration is generally damaging to long-term prospects for growth and development, and should be abandoned in favour of multilateral or unilateral liberalization.12

However, as we shall document below, over recent decades there has been a gradual recognition of the value of regional agreements as a way of catalysing economic growth, trade and investment. This shift in the consensus view is partly the consequence of those agreements becoming increasingly ambitious in terms of embracing more frequently a ‘deep integration’ agenda (e.g. including investment, labour mobility and service trade provisions), and also because of the stagnation of the multilateral trading system since the early 2000s (Mattoo et al., 2020). In the face of growing protectionism globally (Fajgelbaum et al., 2020), the multilateral option may thus no longer be viable.

That said, the truth of the matter is that quantifying the growth benefits from regional integration is a lot more complex than might initially be anticipated. Ceteris paribus is the chief complicating factor, in the sense it is difficult to separate the benefits derived from integration from other factors that influence long-term growth performance. For instance, the SMP project coincided with the formation of monetary union, culminating in the establishment of the Euro in 1999. An additional consideration in the case of the EU is that its membership has considerably expanded since the implementation of the SMP—progressive enlargements has meant that empirical studies have the challenge of dealing with a varying number of member states over time. This obviously complicates the calculation of the benefits derived from the SMP, as it is difficult to separate the impact derived from the expansion of membership from the impact of membership itself.

On the other hand, the advantage of studying the economic impact of the EU’s SMP programme is not only that it received intense academic scrutiny but that sufficient time has now passed to do a proper evaluation. Although there are still methodological problems to contend with, post hoc studies are much more reliable than ex ante assessments.

What we do know is both sobering and encouraging at the same time. Early studies on the potential impact of deepening European integration showed large variations but the impacts were generally quite modest in magnitude.13 Combining both micro- and macroeconomic approaches to the estimation of potential benefits, the officially commissioned Cecchini Report (Emerson et al., 1988) forecast total static benefits from removing barriers to trade, technical barriers, economies of scale and greater competition under the SMP ranging from 2.5% to 6.4% of GDP over the course of a decade. The Commission’s own calculations were framed in the sense of ‘non-Europe’—the cost of ‘doing nothing’ (an approach to the analysis which, incidentally, is worthy of replication for the African continent). Using a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model incorporating increasing returns to scale, changes in price-cost mark-ups and capital stock adjustment, Harrison et al. (1994) projected that competition and scale effects resulting from the SMP would raise EU GDP by 0.7% and the total impact on EU GDP would be 2.6%. In addition to this one-off static gain, a flurry of subsequent studies also highlighted the potential of dynamic gains from the SMP, estimating a permanent GDP growth bonus of between one quarter and nearly 1% point attainable thanks to the higher income, savings and investment (Baldwin, 1989; Gasiorek et al., 1992; Haaland and Norman, 1992).

With the benefit of hindsight, what do the more recent academic studies show us? Reviewing the available empirical evidence at the time, Boltho and Eichengreen (2008) concluded that EU GDP was some 5% higher than it would otherwise have been without the establishment of both the Common Market and the SMP. Using a gravity model, Gil et al. (2008) estimated that the associated GDP gains to date from the SMP would reach 4.4%, with poorer peripheral countries on average gaining proportionately more than core countries. A more recent extensive (and presumably much more reliable) ex ante study, using a gravity model, by Mayer et al. (2018) studied the impact of the establishment of the SMP over the period from 1950 to 2012, and replicated/echoed the results of Gil et al., i.e. it had increased GDP for member states on average by 4.4%, although the authors noted quite a large dispersion around the mean, depending on the modelling scenario.14 These findings were in line with the initial Cecchini Report estimates.15

Nonetheless, Mayer’s study has been disputed in the literature. in’t Veld (2019) looks at both the trade channel (through the elimination of trade tariffs and reduction in non-tariff barriers), as well as the impact of increased competition (through reduced mark-ups and lowered prices). The combined impact of these two channels was found to have raised EU GDP by 8–9% on average over the long run (in’t Veld, 2019:803). These findings are larger than both the ex ante estimates reported in the Cecchini report, and the estimates found in Mayer et al. (2018) and a similar study by Felbermayr et al. (2018).16 A more recent contribution to the literature is from Sondermann and Lehtimäki (2020), using a relatively new methodology called the ‘Synthetic Control Method’ (Abadie and Gardeazabal, 2003) to calculate an explicit counterfactual to membership of the SMP. They conclude that the SMP raised real GDP per capita by 12–22%, a finding more in line with the speculative dynamic gains identified by Baldwin (1989).

A final consideration of relevance to current AfCFTA negotiations is the specific role of services sector liberalization in boosting the economic gains from the SMP. Services trade liberalization in the EU has lagged far behind the elimination of tariffs in merchandise trade, but one estimate by Monteagudo et al. (2012) is that it had raised EU GDP by an additional 0.8%. Were services trade integration to be fully implemented, the same study estimated that the GDP gains would be three times higher than this.

Yet despite the best efforts of macroeconomic and growth economists to measure rigorously the economic benefits of the SMP, they do nonetheless have to confront one uncomfortable truth: regardless of their findings, it would be difficult to argue that the EU’s macroeconomic performance, as a block, has been stellar subsequent to the SMP’s implementation. Many more academic articles and books talk about the EU’s growth malaise than its economic dynamism (e.g. Rodrik, 2017; Stiglitz, 2020). Some ascribe this to underlying structural issues such as adverse demographic trends (Todd, 2003); others because of an inherent lack of competitiveness in certain strategic sectors of the European economy, with the European Investment Bank (2016:3) claiming that Europe had suffered “a two-decade long decline in competitiveness”.

The counter argument is of course that without the SMP, the EU’s growth performance would have been more disappointing still. Yet another view would be that the problems have arisen because of policy decisions taken subsequent to the implementation of the SMP: chief among the potential culprits is the way in which the Euro was introduced. As with all matters associated with European integration, that point has been hotly debated and contested among economists, with US-based economists generally being much more critical than those in Europe.17

To sum up, the results of all macroeconomic policy analysis crucially depend on the choice of model, the assumptions made and the quality of the data. To the lay person or someone without a background in this kind of modelling approach, the recognition of these constraints often results in scepticism towards the whole exercise. Nonetheless, Boltho and Eichengreen’s (2008) conservative assessment probably still holds: that the growth effects were detectable, but not particularly large, and that some of these growth impacts may well have occurred even in the absence of the SMP, since underlying economic forces would almost certainly have pushed for freer trade and less regulation in Europe in any case.

3.2. Lesson #2: But the Trade Impacts are Clearer…

Fortunately, we are on firmer ground when discussing the trade impacts. Ex post empirical analyses of international economic integration agreements suggest a considerably larger effect of such agreements on members’ trade than typical ex ante CGE models (Bergstrand, 2008). Indeed, Nilsson (2018:11) makes the crucial point that CGEs are likely to systematically underestimate the gains from regional integration, particularly for developing countries. As we know from the seminal paper by Hummels and Klenow (2005), the extensive margin (i.e. the expansion/diversification into new products) accounts for around 60% of the increase in exports of larger economies, rather than the intensive margin (increases in existing export products), something existing trade models are poorly equipped to handle. Kehoe et al. (2017) note that one of the main such shortcomings of the CGE approach relates to the need to deal with cases where initial levels of trade are low, especially if trade barriers are prohibitive.

In the previous section we cited a recent extensive (and presumably more credible) ex ante study by Mayer et al. (2018) assessing the impact of the establishment of the SMP over the period since its formation up until 2012. In their preferred simulation, based on an OLS estimator, these authors found that the SMP had increased trade between EU members by 109% on average for goods, and 58% for tradable services. These magnitudes broadly confirmed earlier results by Gil et al. (2008) who also used a gravity model to measure the impact of the different phases of EU integration on trade, with their results showing that both trade growth between the original member states and successive enlargements boosted intra-bloc trade. Moreover, their results suggested that the deepening in the integration process led to more trade creation among members. Using a similar modelling approach, Baier et al. (2008) presented evidence showing that after accounting for all bilateral and multilateral price changes as a result of liberalization, the (partial) effect of the SMP on members’ trade was larger than in traditional gravity equations, raising trade by as much as 127–146% after 10–15 years. By contrast, the same authors compute that membership in the European Free Trade Association raised trade only 35%, again driving home the benefits ascribable to a deeper, more ambitious regional integration agenda.18

Once again, however, different methodological approaches provide different results. As noted in the previous section, the results of Mayer et al. have been disputed by in’t Veld (2019). Based on the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) estimator (which corrects for potential bias related to heteroscedasticity arising through log-linearization and is better able to deal with zeros in product lines where there is no existing trade), the trade effects are reduced, although they are still significantly positive. The PPML estimator puts more weight on pairs of countries with large levels of trade and yields a total effect of EU trade integration of 55% for goods and 33% for services.19 A further contribution to this literature is provided by Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare (2014), who undertook a more disaggregated analysis, introducing multiple sectors and intermediate goods into the modelling. They compute much smaller gains compared with the aforementioned studies by Baier et al. (2008), Gil et al. (2008) and Mayer et al. (2018)—just a 20.1% increase for total trade and a 34.8% increase in intermediate goods.20

The larger trade impact is also disputed in an earlier study by Gil et al. (2008), who note that it is difficult to reconcile large trade effects, based on the OLS estimator, with observed intra- and extra-EU trade flows. In particular, they note that there was little strong evidence of faster intra-EU15 (i.e. EU with 15 member states) trade growth (due to the SMP: intra-EU15 imports increased by just 40% between 1990 and 2000, while their extra-EU28 imports rose by 60% over the same period. The authors recognize that this discrepancy could partly be explained by a price rather than a quantitative effect, through lower prices of non-EU imports,21 offsetting the effects from stronger trade integration within the EU. However, it is also conceivable that the large OLS-based trade effects reported in Mayer et al. are mostly driven by the Central and Eastern European member states that joined since 2004.

An additional level of complexity is added by the trade impact of the European Monetary Union (EMU). It is not a simple matter to extricate this impact, partly because of the overlapping implementation periods, but also because not all members of the SMP also signed up to monetary union (including relatively large economies such Denmark, Hungary, Poland, the UK and Sweden). Most trade economists believe that the existence of a common currency greatly facilitates trade.22 Glick and Rose (2016) found that the EMU boosted exports by around 50%. Yet their strong positive result for the ‘net EMU effect’ has been questioned and recent advances in econometric techniques show that the impact of currency unions on trade may be more uncertain than previously thought. When applying a more advanced gravity model using the PPML estimator to more than 200 countries trading over a long time frame (65 years), Larch et al. (2018) find that the benefits of possessing a common currency are a lot less compelling. Most relevant for this review, their estimates for the Euro effect are economically small and statistically insignificant.23

To sum up, there is a clear consensus that the SMP has positively impacted on intraregional trade in the EU, but the range of estimates is large—from around 20% to as high as 146%. Moreover, by contrast to the shallow integration achieved for Canada, Mexico and the United States within NAFTA, extraregional trade growth was in fact greater than intraregional trade growth in the EU. This has an especial relevance for the African continent, where the objective of the AfCFTA is not only to increase intra-African trade but also raise the continent’s competitiveness and capacity to export vis-à-vis the rest of the world. The EU experience suggests this is an achievable goal.24 However, given the acute infrastructural deficits on the African continent, it is clear that to produce similar results a lot of efforts will need to be made in trade facilitation.25 We will come back to this point at the end of this paper.

3.3. Lesson #3: Deep Regional Integration is a Long-Term Goal

The African continent is understandably in a hurry—its aspirations for establishing a unified continental market can be traced back at least to the Abuja Treaty of 1991 (Juma and Mangeni, 2018). At that time, the economic and political circumstances in Africa were arguably not propitious to embark on such an ambitious programme—it was a period characterized by structural adjustment, low commodity prices and a peak in civil unrest and conflicts across the continent, so much so that the 1980s and 1990s are often considered in developmental terms as ‘lost decades’ (Mkandawire and Soludo, 1998).

Two decades later, after a period of prolonged economic growth, the continent now seems intent on moving ahead with the regional integration agenda as rapidly as possible. Africa is also better placed now for successfully effecting such a change, because its productive base is much more developed, with a significant, if still insufficient, economic diversification into newer, high value-added sectors (McKinsey Global Institute, 2010). When the AfCFTA came into force on 1 January 2021, countries that had already deposited their ratifications (currently 36 of them) started implementation, with a linear reduction in their existing intra-African tariffs on 90% of tariff lines. The ultimate objective is the liberalization of 97% of tariff lines, but this will take a slightly longer time frame—for non-Least Developed Countries (LDCs) a decade, and for LDCs, 13 years (Table 2).

| Tariff reductions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For non-sensitive products | For sensitive products | For excluded products | ||

| Country classification | Developing countries | Fully liberalized over 5 years (linear cut) | Fully liberalized over 10 years (linear cut) | No cut |

| Least developed countries | Fully liberalized over 10 years (linear cut) | Fully liberalized over 13 years (linear cut) | No cut | |

Source: Adapted from ECA (2020).

Schedule for the elimination of tariffs under the AfCFTA

Some observers take these timelines as evidence that the continent is not yet ready for the AfCFTA (e.g. Pilling, 2020), yet it is often not realized the extent to which building a regional market is a long-term project. The reduction in transaction costs involved in border formalities is often more important to trade than customs duties but eliminating these costs can be a complex process; it took 11 years from the establishment of the EEC in 1957 to establish a customs union and, as Schiff and Winters (2003:72) remind us, it took until the mid-1990s to get close to having ‘invisible borders’ between a subset of its members.

Moreover, not all member states implemented at the same pace. By 1997, 4 years into the Single Market, nearly 30% of directives were not yet implemented by at least one member state and a number of the original 279 measures had not even been adopted by the Council of Ministers (Phelps, 1997:3). While in clear cases the Commission (backed by the European Court of Justice) started infringement procedures, in the first years of the Single Market the number of unimplemented or partially implemented directives remained high (Sondermann and Lehtimäki, 2020).

Two decades after its official completion, the EU internal market was still not fully established. Reflecting on the 25 years since the instigation of the SMP, in 2012 Italian economist Monti produced a report for the European Commission that laid out in clear terms the ‘missing links’ and ‘bottlenecks’. In many areas, the report concluded, the Single Market existed on paper but in practice multiple barriers and regulatory obstacles continued to fragment intra-EU trade and hamper economic initiative and innovation. These included persistent barriers in product and services markets, but also in the areas of digital and capital markets and banking unions. In the services sector, Monti (2010:53) drew attention to the fact that

“Services markets remain strongly fragmented with only 20% of the services provided in the EU having a cross-border dimension. As a result, the productivity gap between the US and the Euro area remains much wider than acceptable (about 30%).”

In sum, all of this should serve as a reminder that profound and lasting processes of regional integration take time to set up and implement. The AfCFTA is no different. But as long as there is persistence in efforts to implement the agreement, over the course of a decade it should profoundly change the way the continent does business and trades internally.

3.4. Lesson #4: Regional Integration does not Necessarily Lead to Unequalizing Outcomes

All countries wish to gain from regional integration, but in general the outcome most sought after is that the least developed countries gain the most. Many regional integration agreements start with considerable differences in wealth levels among participating countries. At their beginnings, the ratio of per capita income between the richest and the poorest member country was 4 for the Andean Community, 5 for Mercosur, 7 for NAFTA and about 100 for ASEAN (between Singapore and Laos) (Molle, 2016:394).

What can be expected from the AfCFTA? Initial per capita income differences are very large on the continent, with the per capita income of the poorest country (Burundi) being 67 times smaller than that of the richest (Seychelles) in 2019.26 Most modelling exercises into the impact of the AfCFTA do not reveal any tendency toward divergence under the AfCFTA—on the contrary, while larger members benefit more in absolute terms, smaller, poorer economies tend to gain more proportionately (Mevel and Karingi, 2012; Abrego et al., 2020; World Bank, 2020). Yet one of the abiding concerns in any regional integration agreement is that some members will lose out.27

The theoretical perspectives on this are once again inconclusive. Schiff and Winters (2003:70) claim that, from a developing country perspective, “the same basic forces…mean that regional integration between rich countries causes their incomes to converge, whereas integration between poor ones causes divergence.” Their argument is based on the premise that North–South Agreements allow low-income economies to specialize more in sectors where they have a comparative advantage, along Heckscher–Ohlin lines, in primary commodities, agriculture and low-tech manufacturing. This then allows the higher-income partner to specialize on more technologically advanced sectors in manufacturing and services. For South–South Agreements like the AfCFTA, by contrast, Schiff and Winters argue there is little scope for rising specialization and hence few mutual gains from integration.28

Such arguments are the product of a static, rather than a dynamic, approach to comparative advantage (Lin and Chang, 2009) and are not necessarily borne out by the empirical evidence (see, inter alia, te Velde, 2011; Santos-Paulino et al., 2019).29 It should also be stressed that Schiff and Winter’s argument partly hinges on the extent to which there is a dichotomy between ‘North–North’ integration, based on ambitious goals of ‘deep integration’, aiming to eliminate all barriers to the movement of goods, services, people and capital, and the perceived ‘shallow integration of South–South regional blocks (Schiff and Winter, 2003:115). Such arguments do not really apply to the AfCFTA, as it also is aiming, like the EU, at a high degree of integration, including the liberalization of investment flows, services, free movement, and the eventual establishment of a customs union and common currency.

What can Europe’s experience tell us about the likelihood of equalizing economic forces predominating over unequalizing ones? Historically, the EU integration narrative has been based on the argument that deeper economic integration would inevitably lead to faster income convergence (Sapir, 2011; Alcidi, 2019). Yet at the beginning of the process of establishing the SMP, the European Commission had an uphill struggle to convince citizens and EU member states, particularly on the periphery (e.g. Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland), to fully support its implementation. Echoing contemporary concerns in Africa that the lion’s share of benefits from the AfCFTA will accrue to continent’s largest economies, the peripheral countries were worried about the consequences of opening their weaker national markets to the high-productivity firms of northern Europe (Amin and Tomaney, 1995; Mold, 2000). There were widespread fears that the forces of divergence would be stronger than those of convergence within the block, leading to a difficult adjustment to slower growth, an inability to compete and a corresponding loss of employment.

These concerns germinated, intellectually speaking, in the form of the ‘New Economic Geography’ (Krugman, 1991a; Venables, 2007), whereby it was posited that, as countries specialize to reap the gains of trade integration, there could be an increasing agglomeration of production and concentration of income in higher-income countries. This outcome was contingent on a combination of the three principal variables: the prevalence of scale economies, the degree of market density and the geographic distance from core markets, as well as the external economies (or spillovers) arising from co-location of industries in industrial hubs (Fujita et al., 1999). The stylized facts seemed to initially lend some credence to this view—whereas during the 1970s, the distribution of industries across European countries became more similar, in the following two decades (and coinciding with the implementation of the SMP) there was increasing divergence, suggesting growing specialization. Between 1980–83 and 1998–2001 all countries except the Netherlands experienced an increase in specialization in their industrial structure (Venables, 2007:42).

Yet in retrospect it seems that convergence and ‘centripetal’ forces have tended to dominate over divergence and centrifugal forces. Econometric results cited earlier (Gil et al., 2008; Mayer, 2018; Sondermann and Lehtimäki, 2020) have tended to show that, in terms of economic growth, smaller countries benefited more from deeper regional integration in Europe. Between 1980 and 2000, European economic integration was accompanied by falling inequality between countries (although not within countries) (Puga, 2001; Venables, 2007).30 There are some additional theoretical reasons why this should be the case. For one thing, trade liberalization allows smaller economies to gain through access to the larger market (Scitovsky, 1960). But also, as stressed by Sondermann and Lehtimäki (2020), by establishing a common market, smaller economies get access to production factors, such as capital and high-skilled labour, from other EU partner countries. Due to the expectation of higher marginal returns, incentives for investment and migration increase.

More recent trends in income convergence across the EU add some complexity to this picture, however, and highlight three different patterns (Alcidi, 2019): first, a strong average convergence across member states since the turn of the century, essentially driven by the dynamics of faster growing newer Eastern European members; secondly, many Southern regions, both in old and new EU member states, struggle to keep pace with the rest of the EU. This is particularly true since the 2008–9 financial crisis, when austerity policies in Greece, Spain and Italy led to extremely high levels of public debt and unemployment, rising to 25% of the working population.31 Finally, in the case of Eastern European member states, a very pronounced trend has existed toward internal income divergence. What is driving these new trends is a salient point, and beyond the scope of the present paper, but it is probably related as much to domestic policies and countries’ differing abilities to recover from the 2008–9 financial crisis as it is to do with the EU’s regional policies.32 That said, as noted earlier, a lot of criticisms have been voiced over the Eurozone’s post-crisis monetary and fiscal policy and whether this could have been handled better (Stiglitz, 2020; Weisbrot, 2015; Varoufakis, 2015).

Regardless of the emerging complexity of trends in income convergence, one reason why Europe may have been relatively successful in the initial stages of the SMP in mitigating any centrifugal forces was that it was able to effect fiscal transfers to poorer members. Prior to the SMP, in the mid-1970s, Community expenditure on regional policy constituted just 5% of the total budget, but by the beginning of the 2010s, this figure is closer to 36%, making cohesion the second most important category of expenditure after the Common Agricultural Policy (Hodson, 2012:496). Although still small in absolute terms,33 for some member states (particularly Ireland, but also for Greece and Portugal) these funds represented a significant complement and helped them build their infrastructure. Major increases in infrastructural spending were facilitated by the establishment of EU Structural and Cohesion Funds in 1975 and 1994, respectively. Thanks largely to EU structural funds, for instance, Spain’s spending on its train network (the AVE) and Portugal’s road networks were improved immeasurably during the 1990s and early 2000s compared with before the SMP. Greece saw large improvements in highways and ports. It has been estimated that EU support accounted for almost 15% of total investment in Greece in the 1994–99 period, for around 14% in Portugal, 10% in Ireland and 6% in Spain (European Commission, 2001). Barry et al. (2001) discuss how structural funds contributed to facilitating Ireland’s ‘economic miracle’ so that, whereas in the early 1990s Ireland was one of the poorest countries within the EU, by the mid-2000s, it had become a relatively high-income country, with a per capita income significantly higher than in the UK.34

To sum up, while full income convergence was never a realistic objective (Alcidi, 2019), it may be concluded that fears of regional integration driving economic divergence have not been well founded in the European case. There are divided opinions among academics about the degree to which any convergence was due to the active policy of the EU.35 To some extent, these arguments about the effectiveness of regional policy in mitigating any unequalizing forces may be somewhat academic in the case of the African continent. Despite its resource wealth, in terms of per capita income the African continent is still a poor one. Thus, while the EU was able to effect fiscal transfers to poorer and smaller new members, transfers will inevitably be more modest in the case of the African continent. One positive development at the Fourth Meeting of the AfCFTA Council of Minister in February 2021 was an agreement to establish an AfCFTA Adjustment Facility, with a resource base of US$ 7.7 billion over the next 10 years. The objective is to cushion African governments from the AfCFTA-induced fiscal losses and allow all countries and their private sectors to make smooth adjustments to the AfCFTA. Nonetheless, embracing other approaches to supporting poorer member states during the implementation period will still be necessary.36

3.5. Lesson #5: Disputes are Inevitable during Implementation—and Need Managing

In much of the media, periodic trade disputes in Africa are often taken as evidence that regional agreements will not work, as they will not be properly implemented and respected by the trading partners.37 Yet in fact such disputes are commonplace in all regional blocks. The EU experience is replete with examples of clashes of this kind. Trade in agricultural produce in Europe was periodically a focus for disputes. In 1990, for instance, French farmers attacked trucks carrying imported cattle, lamb and meat, with British, Dutch and German truckers saying they felt terrified even to drive through France (Greenhouse, 1990). Such visceral conflicts persisted for a considerable period of time.38 Moreover, disputes have gone beyond merchandise trade and have included confrontations in areas like financial services and investment where some member states accused others of unfair competition and that the European market was not a ‘level playing field’ (see Ramsey, 1995; Mold, 2000).

The quarrels have not been only cross-border in nature. The EU has often been vexed in terms of the policies of its member states towards third parties. This is well illustrated by the EU’s experience over non-tariff barriers on trade with non-member countries. For example, in 1983 the French government threatened controls on imports of videocassette recorders from Japan. Similarly, in 1988 France and Italy sought protection from Korean and Taiwanese footwear and were allowed national Voluntary Export Restraints—the EU authorities essentially accepting the adoption of national trade policies despite their mission to create a Single European Market. The impasse was eventually overcome by extending the policy towards imports from Korea and Taiwan to the whole of EU. According to Alan Winters (1997:904), the EU has thus been forced into a position whereby at times it has adopted policies based on those of the most protectionist members and propagated them over the whole EU.

Similar issues are already raising their head on the African continent, with, for instance, differing interpretations as to the wisdom of individual member states signing up to trade deals with third parties during the implementation period of the AfCFTA; the case of Kenya, for instance, which has recently been negotiating bilateral trade agreements with both the United States and the UK. In principle, of course, this should not represent an excessive problem if rules of origin are applied effectively. Although there are ambitions to move toward a continental-wide customs union, the AfCFTA is currently a free trade area, and hence allows individual member states to reach agreements with third party trading partners. However, the liberal application of rules of origin significantly raises the cost of trade and, at a time when countries are trying to prime the intra-African component in trade, it is important that member states align their policy toward third parties as far as possible. To conclude, the lesson from the EU example in this domain is that trade disputes will be inevitable between AfCFTA signatories but need to be dealt with as expeditiously as possible in order to maintain the coherence and integrity of the continental market.

3.6. Lesson #6: The Business Community must Play a Major Role in AfCFTA Implementation

“Today there are African businessmen and women interested in regional markets…The failure to bring on board these interests is tantamount to a performance of Hamlet without the prince. We are talking here as bureaucrats and academics, and the actual big actors are not involved. And we don’t fully understand what their interest is.”

An extremely important lesson coming from the European experience is the pivotal role of private sector actors. The establishment of the SMP was essentially driven by business interests. It has even been argued (Cowles, 2012:112) that a key transnational business organization—the European Roundtable of Industrialists (ERT)—encouraged the European Commission to support a single market initiative in the first place. In fact, the ERT’s creation marked the first time that major companies openly mobilized to influence the regional integration agenda, issuing a memorandum entitled ‘Foundations for the Future of European Industry’, calling on political action to create a unified European market.

Throughout the period of negotiations, the business sector continued to be instrumental in pushing the SMP agenda forward. In January 1985, the Chief Executive Officer of Philips, Wisse Dekker, unveiled a plan ‘Europe 1990’, before 500 commission and industry officials in Brussels. The ‘Dekker Plan’ laid out steps in four key areas: the elimination of border formalities, the opening up of public procurement markets, the harmonization of technical stands, and fiscal harmonization to create a European market within 5 years. Just a few days later, the new Commission President, Jacques Delors, announced the Commission’s intention to create a single market by 1992. As Delors himself noted, the SMP came about “thanks to many people and actors in what became a process … the 1992 process. And I must admit the business actors mattered; they made a lot of it happen” (Cowles, 2012:114).

For the African continent, some key business sector organizations have similarly expressed their enthusiasm for the AfCFTA (e.g. Afrochampions, East African Business Council). Some prominent businesspeople have also made public pronouncements about the potential of a unified continental market under the AfCFTA. But awareness about the AfCFTA is still relatively limited among the broader business community,39 who are far from being in the driving seat regarding moving the agenda forward. This is something that needs to change. As noted earlier, Mkandawire (2014:14) stressed “the failure to bring on board these interests is tantamount to a performance of Hamlet without the prince”.

3.7. Lesson #7: Large Firms are Major Drivers of Regional Integration Processes

African businesses are predominantly very small, with Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) said to account for 95% of all African firms (Cramer et al., 2020:67). Many analysts argue that ‘SMEs are central to wealth creation by stimulating demand for goods, investment and trade’ in Africa, through their contribution to job creation, their discovery of new markets, and their capacity for innovation. In the public discourse on the AfCFTA, some observers are putting SMEs centre stage (e.g. Vir, 2021).40

This may be mistaken. For solid reasons, smaller firms tend not to trade—they are unable to reap advantages of scale economies, are often understandably risk adverse and cannot confront the fixed costs related to trade across borders. By contrast, precisely because of the intensity of their cross-border transactions, larger firms already with a regional presence have potentially a major role in integrating markets within a regional block (Thomsen and Woolcock, 1993; Blomstrom and Kokko, 1997).

It is often not fully appreciated the extent to which global trade is driven by such multinational corporations. Multinational enterprises are responsible for around 80% of global trade, and half of that is intracompany trade (i.e. transactions between affiliates and/or the parent company) (UNCTAD, 2013). The implications are clear—any regional project that has, as a goal, to raise both intraregional trade and investment needs to count on the cooperation of large firms and multinationals as drivers of the integration process. There is a political economy angle to this too: as noted above, large companies were particularly instrumental in pressuring for reform within the EU and driving the SMP process.

Multinationals are often feared because of their intrinsic market power. We noted earlier the economic geography literature and concerns that the SMP could catalyse a concentrating effect of regional integration, as firms rationalized their production and shifted their preferences in terms of the way they chose to serve their core markets (Krugman, 1991b; Venables, 2007). Krugman’s arguments are particularly pertinent to multinational firms, with an initial presence in many markets, but with a strong rationale to reorganize their productive and marketing operations as barriers to trade and transactions decline under regional integration.

Nonetheless, as noted in Section 3.4, fears of a growing concentration of economic activity by multinationals were not substantiated in the case of the European SMP. On balance most companies did not opt to relocate their operations closer to the larger higher income markets and instead often ended up decentralizing some of their productive functions to take advantage of lower costs in the European periphery. The reasons were tied up with the fact that scale economies are rarely so prevalent, distance costs remain stubborn, and different industries inevitably adopt different strategies for serving the integrated market (Mold, 2000; 2003).

However, what is clear is the initial incentive that deeper regional integration gave to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows within the Single Market. The European Commission (1998) found that intra-EU FDI rose more rapidly than investment outside the EU following the introduction of the SMP. Germany and the UK, typically the two largest outside FDI investors in the EU, switched their investment from the United States to the EU, beginning in the late 1980s (Schiff and Winter, 2003:120). Not only did the Single Market induce greater intraregional FDI, it also made member countries more attractive to investment from US, Japanese and other third-country firms (Motta and Norman, 1996; Mold, 2000).41 Even before the coming into force of the SMP, the European Commission (1998) noted that the EU’s share of worldwide inward FDI flows increased from 28% to 33% during 1982–93.

However, the Commission’s early evaluations have to be tempered by the fact that the impetus given to greater FDI inflows by the SMP—very notable in the 1990s up until the mid-2000s—was not sustained, and eventually declined to more ‘normal’ levels (Dellis et al., 2017). The figures also must be put in the context of a global surge in FDI in the 1990s and early 2000s—measured as a share of the global total of FDI, after peaking in 1991, when the EU15 were responsible for around half of global FDI totals and declining thereafter.42 In his review of the evidence, Flam (2016:64) is quite categorical on this matter, arguing that “there is no empirical evidence that the Single Market Program has stimulated FDI between EU countries more than FDI from outside countries.”

The conclusion from the data would seem to be that processes of deep integration can indeed provide a stimulus to greater FDI, but that stimulus does not last indefinitely. In global terms, the most robust determinants of FDI are still market size and income—and, on that score, as the world’s largest integrated market, the EU conserves some intrinsic advantages.43 A lack of investment in productive assets is perhaps one of the binding constraints for African countries. This is often the product of excessively small market size. The AfCFTA will remove that constraint—something that should in principle benefit most some of the continent’s smaller economies.

To sum up, the European experience does indeed show that deep regional integration can provide a significant, if temporary, boost to FDI inflows. Of course, outside a few select sectors (e.g. banking, automobile manufacturer, cement), the firms that will have a truly continental reach will be few and far between. Most companies are likely to have a regional base and still focus on their sub-regional markets. And if only from a balance of payments perspective,44 it is to be hoped that the majority of that investment will be intra-African in nature. This would surely be one of the most effective ways of increasing the degree of connectivity between African economies.

3.8. Lesson #8: Competition Policy and Consumer Protection are Essential

The extent to which the African market is profitable is often not sufficiently appreciated. According to the IMF (2019), average firm profitability in sub-Saharan African countries is significantly higher (by 10–20%) compared with other emerging market and developing economies. Firm mark-ups are also about 11% higher in sub-Saharan African countries relative to other countries at a similar level of development, thereby implying a lower degree of competition. It has long been recognized that measures of concentration (reflecting firms’ market power) in manufacturing sectors in large developing countries are typically between 50% and 100% higher than in developed countries (Rodrik, 1988).

Mold and Atsin (forthcoming) note that in 2017 the largest 387 firms in Africa, ranked by sales, recorded a total of US$ 41.5 billion in profits, reflecting an average return on sales of 8.4%. More impressive still was the average profitability (expressed as reported profits as a share of total sales) of the largest African firms—the top 100 most profitable firms reported an average profitability of 29.5%—a level of profitability around three times higher than that reported by the S&P 500 in the same year. The services sector, in particular, seems to be particularly lucrative, with high rates of return reported in sectors like ICT, distribution and banking (ECA, 2020).

High rates of return are a double-edged sword—they provide of course a strong incentive to investors, but usually reflect high barriers to entry, a lack of market competition and high prices for consumers. In principle, by combining markets, regional integration makes it possible to reduce monopoly power, as firms from different countries are brought into more intense competition with each other (Schiff and Winters, 2003:49). This is precisely one of the main channels through which welfare benefits are generated for consumers through regional integration. Making sure that the benefits do not accrue solely to producers and traders but materialize in the form of reduced prices for consumers is fundamental if the AfCFTA is to be a success. The findings of several past studies (Raff and Schmitt, 2009; Francois and Wooton, 2010) suggest that there are risks that the gains from trade liberalization in merchandise goods can lead to higher concentration and oligopolistic pricing in the retail or transport sectors. In other words, some services sectors could effectively hijack the gains from greater trade derived from the AfCFTA if they are also not sufficiently competitive (Francois and Hoekman, 2010:652).

On this point, the European experience is particularly instructive. The SMP has been accompanied by competition policies that have on occasions displayed their legislative teeth. The European Commission has considerable powers to investigate suspected abuses of EU competition law and prohibit anti-competitive practices. Most famously, the Commission has the right to make on-site inspections without prior warning (which the media often call ‘dawn raids’). It does this by issuing injunctions against firms. To back up these demands, the Commission has the right to impose fines on firms found guilty of anti-competitive conduct. The fines vary according to the severity of the anti-competitive practices, with a maximum of 10% of the offending firm’s worldwide turnover (Baldwin and Wyplosz, 2015).

What is the evidence of the effectiveness of these policies? As expected, price dispersion—a good indicator of the degree of integration and competition within a unified market—decreased across the EU under the influence of increased competition: the EU’s price dispersion index declined by one third between 1993 and 1996 and by one fifth between 1995 and 2000 (EC, 2001). In some European countries, for instance, prices of international and national long-distance calls fell by 30% or more, with price declines of mobile phone services being particularly significant.45 In fact, the European telecommunications sector provides a good example where liberalization actually boosted total output, improved the product range, reduced prices and supported net job creation.46 Although employment in some sectors may have initially been reduced because the former monopolists had to rationalize activities due to greater regional competition, it has been argued that these losses were more than compensated by the creation of employment by new entrants into the sectors (Molle, 2016).

In aggregate, it is estimated that the competition channel added an additional 2% to the GDP effects of the SMP (in’t Veld, 2019:809). However, the degree of integration of markets has clearly been uneven. In a review of the empirical evidence of the impact of the SMP on firm mark-ups, Badinger (2007) found that reductions were found for aggregate manufacturing and construction. By contrast, mark-ups had gone up in most service industries since the early 1990s, confirming the weak state of the Single Market for most services and suggesting that defensive anti-competitive strategies had emerged in some EU service industries.

The conclusion would seem to be that in matters of competition policy, the AfCFTA Secretariat will need to be empowered and carry a big stick. Whether the AU member states are prepared at present to countenance such a situation and concede a degree of sovereignty in these matters is a matter of conjecture, but it is a logical corollary of creating a unified continental market. Integration can only confer substantial institutional benefits if real authority is delegated to central institutions (de Melo et al., 1993:37).

There is one final nuance to this lesson. The European experience suggests that it is probably wiser to avoid institutional regulatory overreach in the beginning and start by formulating common competition policies with respect to only the most extreme cases (monopolies, state aids). But there will still be a need to make sure that the liberalization of markets under the AfCFTA is not distorted by so-called behind the border measures. For instance, a company that has a strong position in its domestic market may be able to accumulate the financial buffers it needs to compensate for losses incurred by dumping its products on the markets of neighbour countries. In such cases, there is clearly a need for effective anti-dumping or competition policy.47

3.9. Lesson #9: The Importance of Keeping the General Public Well Informed

One final lesson from the European experience for the AfCFTA is the importance of keeping the general public well informed about the integration process. As Hobolt (2012:716) notes, for decades European citizens were viewed as largely irrelevant to the process of integration. But the times when elites could pursue European integration with no regard to public opinion are long gone. As the EU has evolved from an international organization primarily concerned with trade liberalization to an economic and political union with wide-ranging competences, public opinion has become more important. At no time in the EU’s history has the importance of public opinion become more evident than during the campaign of Brexit. Arguably, the poor level of knowledge among the British public about what membership of the EU entails and the benefits it confers was partly responsible for Brexit.48

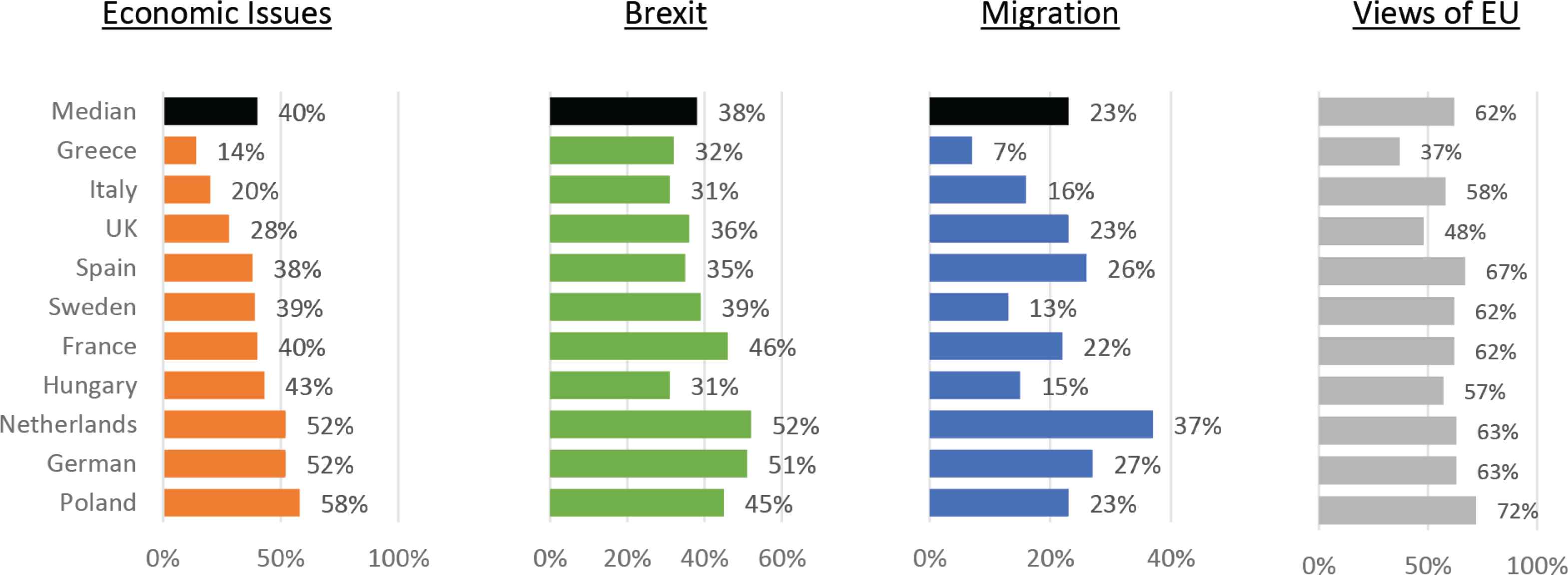

The current state of public opinion across the EU shows some worrying trends (Figure 1). While in most countries the majority of the population still has a generally favourable view of the EU (with a median level of positive views at 62%), on a wide range of issues with regards to how the EU has handled economic and social issues such as economic management, Brexit and migration, public opinion is highly critical. What this means for the future of the Union is a matter for debate.

Public opinion of the European Union’s handling of economic and social issues (2018). Percentage of the population that believes the EU has handled these issues well or very well. Views of the EU reflects the percentage of the population with an overall favourable view of the EU. Source: Pew Research (2019).

The lesson for the AfCFTA would seem to be that technocratic exercises in regional integration rarely stand the test of time. Either you carry the general public with you on these journeys, or eventually a backlash will occur. As Mkandawire (2014:11) puts it,

“Pan-Africanism of the population finds no room for expression. There has never been a referendum to consult on whether the country should join this regional or exit a regional arrangement. If the head of state gets angry with one of his/her colleagues, the country pulls out. There’s no sense that this should be explained to and approved by the people.”

According to the academic literature, the costs of a lack of information could be particularly high for the African continent. Africa is rightly proud of its high degree of ethnic and linguistic diversity. However, there are costs associated with such diversity. A general finding of the political economy literature is that more heterogeneous populations typically face higher political costs in the provision of public goods like the funding of processes of regional integration (e.g. Alesina et al., 2003; Spolaore, 2015). The African continent starts this ambitious project of regional integration from a good place—according to an opinion poll carried out by Rockefeller Foundation of over 2000 African citizens across the continent, 77% of the respondents believed that the AfCFTA was an important initiative in supporting economic development.49 That level of enthusiasm needs to be maintained, by making sure that the general public is well aware of the benefits that the AfCFTA will confer, and making sure that misconceptions and misinformation do not take root.

4. CONCLUSION

This paper started by alluding to Hegel’s rather pessimistic claim that humankind learns nothing from history and, by implication, is condemned to keep repeating the same mistakes. It argues that there is no reason for this to be the case, particularly with regard to regional integration—there is now a large body of literature and research and an accumulated knowledge of practical experience in regional integration, and policymakers in Africa can draw on this knowledge to avoid the pitfalls.

The paper has focused on the evidence from the EU, undisputedly, one of the most advanced and ambitious examples of regional integration in the world. The review of evidence contained herein has by necessity been selective: the breadth and depth of the research into the economic impacts of the EU would be impossible to review comprehensively in a single journal article. But the author has tried to select the most representative strands and commonly cited articles in the respective literatures.

After more than six decades of existence, the EU is still very much a project in progress, with no distinct end goal beyond achieving ‘ever closer union’. Former Commission President Romano Prodi once compared the process of European integration to riding a bike; one had to keep pedalling forward to avoid falling (Sala, 2012). This paper highlights the fact that the SMP has not followed a linear path of progress but has suffered many setbacks—and often fallen off the bicycle.

The AfCFTA can expect to suffer similar setbacks, but fortunately has a large degree of political consensus to support it. Translating that political consensus into action is the true challenge. This article has highlighted the fact that there are some valuable lessons to learn about both what to do and what not to do from the European experience. The parallels are especially pertinent in the sense that, like the SMP, the AfCFTA covers not only trade but also investment in the free movement of people and that it established a common external tariff. In other words, they are both projects of ‘deep integration’, with all the corresponding benefits and risks that this entails.

In a profound reflection on the lessons from the EU’s experience of regional integration, Molle (2016) focuses in on both the things it did do, but should not have done, and the things it failed to do.50 Of the former, he stresses two main areas—a tendency to overregulate the economy, and the protective regime for agriculture.51 The second type of failures applies to things the EU has not done but should have done. Many things come to mind in this category, including incomplete tax harmonization leading to tax evasion and fraud; the non-existence of a European corporate statute, preventing firms from organizing themselves efficiently; and the piecemeal and slow integration of the service sectors (Molle, 2016:349).52

For the African continent, things are rather different. With the benefit of hindsight, the African continent can avoid some of the more obvious pitfalls. That is the basic premise of this paper. As stressed at the beginning of the paper, the AfCFTA is in many senses unique, in that nothing has been attempted on this scale before—a market of more than 1.2 billion people and incorporating 55 member states (if the final member signs up). It will inevitably have to find its own path. Moreover, African integration is not a tabula rasa, and despite scepticism in some quarters about the achievements of regional blocks across the continent, some of them have proved fairly effective in achieving their initial goals.53

To conclude, in making the case for the implementation of the AfCFTA, Africa currently finds itself at a similar juncture to Europe in the late 1980s. With the backing of its UN partners like UNECA and UNCTAD, the regional development banks (AfDB and Afreximbank) as well as the donor community (including the EU, GIZ, TMEA, etc.), widespread needs for technical support can be met in areas like impact evaluation and capacity building, as member states finalize negotiations and enter into the implementation stages of the AfCFTA. Studies such as that produced by the World Bank (2020) point to the extent to which a successful outcome will be dependent on trade facilitation measures, and here the donor community’s support will be crucial too. There is also a pressing need to raise awareness among stakeholders and civil society about the nature and the scale of ambition of the project. Above all, as Alan Winters (1997) points out, the EU experience teaches us that it is necessary to be realistic about what integration will actually achieve: excessive expectations of what can be achieved has cast a shadow over previous regional processes, both in Africa and beyond. This time must be different—we should learn the lessons from history—and prove Hegel wrong.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

There has been no funding for this study. The author worked on his own schedule voluntarily.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Augustin Fosu, Raphie Kaplinsky and Francis Mangeni for their invaluable comments on an earlier draft of this paper, as well as two anonymous reviewers. Any errors remain the responsibility of the author.

Footnotes

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), considered one of the major figures of modern Western philosophy.

See, for instance, Hoffman (1966), Heffernan (2000), Gillingham (2003).

For example, Feldstein (2012), Krugman (2015).

Reflecting the aforementioned crises, however, the same poll reveals that Europeans also tend to describe Brussels as inefficient and intrusive, and believe the EU is out of touch—a median of 62% say it does not understand the needs of its citizens. More will be said on this matter in Section 3.9 of this paper.

See inter alia Baldwin and Wyplosz (2016), Flam (2016).

As Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, the economist and central banker who played a key role in the birth of the Euro, once wrote: “After experiencing political oppression and war in the first half of the twentieth century, Europe undertook to build a new order for peace, freedom, and prosperity. Despite its predominantly economic content, the European Union is an eminently political construct” (cited by Spolarore, 2015). Mkandawire (2014:16) makes a very similar point about the African regional integration: “Bureaucrats, both national and regional, say that we must depoliticize the debate around regional integration. But regional integration is a political project. When it functions at all, it functions as a political project.”

Thus, although EU Regional Policy had only been in place since 1989, Sala-i-Martin (1996) compared the regional growth and convergence pattern in the EU to that of other federations that lack a similarly extensive cohesion program and concluded that the EU’s structural policy was a failure. Boldrin et al. (2001) came to similar conclusions. Yet such conclusions are not only precipitous but require comparability of federations and their regions in all other respects, which is empirically challenging.

Geographically, of course, the difference of scale is enormous. The African continent, at 30.4 million km2, is nearly seven times larger than the European Union (4.5 million km2) and with much weaker infrastructure for trade. As Mkandawire (2014:5) reminded us, the United States, India, China, Western Europe, Japan all fit into the African continent, “so when you say ‘integrate Africa’, you are saying integrate US, China, India, France.”

In some senses, the global context may be more propitious to the AfCFTA now than in the 1980s or 1990s. For instance, while the share of intraregional trade in developing and emerging economies had barely changed between 1960s and 2000 (24% and 27%, respectively), since 2000 it has risen markedly, reaching 42% in 2019 (own calculations, based on IMF DoTs, 2020, data). Kaplinsky and Kraemer-Mbula (forthcoming) speculate on several reasons for this—including the rapid growth of developing country markets vis-à-vis the sluggish growth of high-income economies and the fact that the dominance of Chinese-sourced imports into high-income country markets has left little space for exporters from other developing regions, forcing producers to target sales to neighbouring economies. In addition, the differentiated nature of final consumer markets in low-income countries has tended to give an advantage to firms from developing countries. All these structural factors have acted to spur the growth of South–South trade and augur well for the AfCFTA.

A cautionary note should be made regarding the extent to which this snapshot of European experience fails to reflect a long period of incremental change. For a detailed history of the gradual development and deepening of European integration, see the collected volume of Jones et al. (2012). For a discussion of the specific provisions of the SMP, see Cowles (2012).

Although the most important measures came later with the so-called Services Directive in 2006 (Flam, 2016).