The consequences of Brexit for Africa: The case of the East African Community☆

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.joat.2018.10.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Brexit; East African Community (EAC); Computable general equilibrium model; Regional integration; Trade

- Abstract

How will Brexit impact on Africa? This paper looks at the available empirical evidence and carries out a Computable General Equilibrium simulation, focusing particularly on the prospects for the East African Community (EAC). The paper makes three main points. First, while the direct impacts through investment, trade and remittances are likely to be relatively small, African countries may benefit from the creation of new export opportunities. However, these are mainly in resource-intensive sectors that are not considered a priority for the development agendas of most African countries. Second, indirect consequences, through Brexit’s impact on the global economy, its influence on the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the European Union, or a potential reduction in UK development cooperation, are likely to be equally important over the longer run. Finally, one overlooked consequence of Brexit for Africa is that it could undermine confidence in ‘deep’ regional integration processes like the EAC. The paper concludes that the correct response at such a time is not to falter but to redouble efforts towards regional integration through the implementation of the recently-signed African Continental Free Trade Area, while learning the pertinent lessons from Europe.

- Copyright

- © 2018 Afreximbank. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc/4.0/).

1. Introduction

On the 23rd June 2016, the British electorate delivered a largely unanticipated vote to leave the EU. Speculation has continued ever since about its impact on the UK economy, in Europe and the rest of the world. Africa has not been immune to these concerns (e.g., Luke and MccLeod, 2016; Sow and Sy, 2016). This is understandable given the fact that the United Kingdom as well as the EU continue to maintain important investment and trading links with Africa and are major donors. Some of the initial evaluations were quite alarmist. For instance, Tan (2016,18) declared that ‘African economies may be severely affected by Britain’s exit.’

Most of the subsequent academic literature discussing the implications of Brexit for Africa has focused on the terms of post-Brexit trading arrangements with both the UK and the European Union (see, inter alia, ODI, 2016; Mendez-Parra et al., 2016; Holmes and Winter, 2016). This paper takes a different approach by providing a first quantitative assessment of the potential impact of Brexit on trading relations with the African continent. The analysis focuses particularly on the East African Community (EAC) — a regional block with long-standing historical and economic ties with the United Kingdom.1

As one of the most advanced and ambitious regional economic communities on the continent, the East African Community is a good example of African aspirations towards ‘deep integration’, in the sense of going far beyond the simple elimination of tariffs and quotas and acknowledging the fact that effective integration requires measures to reduce all barriers to the free flow of goods, services, capital and labour (Schiff and Winters, 2003). Established in 2000,2 the EAC has already established a Customs Union and Common Market, with plans for moving towards monetary union and an eventual political federation.3 Implicitly, if not explicitly, the European Union has been an important role model for the EAC — for instance, in 2010, a technical team from the European Central Bank visited the region to advise on the achievement of monetary union. Both the United Kingdom and the European Union maintain strong economic ties with East Africa, and the UK is a major bilateral donor, in a region which in the recent past has been highly aid dependent. Because of these points, the EAC represents an interesting case-study of how Brexit might impact on regional blocks in Africa.

This paper does not presume to put forward a comprehensive evaluation of Brexit and its trading impact globally. That would need to be done through a more exhaustive analysis, at a much more disaggregated level.4 Rather, the focus of the paper is on the potential impact of Brexit on the EAC. Economists generally try to measure such macroeconomic shocks through evaluating both direct impacts (e.g., through trade, investment and remittances) and also considering the indirect ones (e.g., through its broader impact on the global economy). Among these indirect channels, the paper postulates that there could be a negative impact through a kind of ‘demonstration effect’ on the prospects for other projects of deep integration like the EAC. It is argued that the short to mid-term consequences, through the direct impacts, are likely to be relatively minor, but for the longer-term, it warns that the indirect impacts could be more consequential, particularly with regard to how it could undermine confidence in processes of deep integration in Africa. The way to avoid this outcome, it is argued, is to redouble efforts to implement the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Section 2 presents some stylized facts on the UK’s role in the global economy and quantifies its principal trading and investment links with Africa. In Section 3, we then look at the depth of those links specifically with the EAC. In Section 4, a computable equilibrium model — the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model — is used to simulate what may happen to trade patterns, should the Brexit negotiations end up with a ‘no deal’, that is, with the UK and the European Union reverting to the standard tariffs imposed on imports from the rest of the world: ‘Most Favoured Nation’ tariffs under the WTO. In Section 5, we discuss how Brexit may affect the EAC region through its indirect links, particularly with regard to how it could undermine regional integration efforts. Section 6 concludes and makes some additional remarks about how the implementation of the recently signed AfCFTA may help mitigate any negative impacts from Brexit on Africa.5

2. The UK economy’s current links with Africa

The first thing to stress is the enormous amount of uncertainty that surrounds the whole Brexit process. At the time of writing (September 2018), negotiations have ostensibly been going on since Article 50 of the Treaty of Rome was triggered in March 2017, notifying the European Union officially of the UK’s intention to leave the block. However, negotiations have been slow and characterised by a relatively few concrete advances. While some general negotiating principles have been agreed, currently nothing is known about the final terms of the agreement. Indeed, questions have been raised if legally it will be possible to enact Brexit; there have already been legal challenges about whether parliament will have to vote on any final agreement reached with the European Union, and calls have even been made for a second referendum once the terms of an agreement have been finalised. As stressed by te Velde (2016: 22), this is crucial because whether the UK is in the Single Market, a customs union with the European Union, or a free-trade agreement (FTA) with the European Union, will determine the options available for UK trade policy towards developing countries. For the British themselves, the decline in sterling was initially the most tangible impact (15% against the US dollar in the first four months after the vote), resulting in a significant decline in real incomes (although some of the losses were clawed back over the course of 2017, sterling has remained weak).

In Africa, the key concerns were initially framed around the way Brexit could impact on the global economic environment. In an interview in May 2016, the Kenyan Central Bank governor, Patrick Njoroge, was already warning that emerging markets would experience significant uncertainty if the UK voted to leave the European Union, to the extent that “the volatility in 2013 surrounding changing US monetary policy would seem like ‘a little kids’ play” (cited by Aglionby, 2016).

When measuring the impact of an event or shock on the global economy, it is first important to get a sense of the relative size of the economies in question, and the depth of their existing financial, trading and investment links. The Africa rising narrative was reflected in part by an acceleration of the continental growth rate since the beginning of the Millennium and consequently leading to an increasing share of Africa in global GDP, from 4.4% 2000 to 5.1% in 2015. That optimistic narrative took a dent in 2016, as commodity prices tumbled and the growth of Nigeria and South Africa (the two largest economies) stagnated. However, it is notable that beyond the major oil and mineral exporters, African economic growth has still been quite resilient (IMF, 2017b). This is particularly the case in resource-poor East Africa, which continues to maintain a rate of economic growth in excess of 5% per annum since 2013 — making it currently one of the fastest growing regions in Africa (UNECA, 2016).

By contrast, the UK’s economic growth has remained sluggish since the global financial crisis of 2008–9, and as a consequence has seen its share of global GDP decline from 3.0% in 2000 to 2.3% in 2015 (Office for National Statistics, 2016). However, the influence of the British economy on global developments — and on Africa in particular — arguably goes beyond its economic size, partly as a function of its deep-seated historical ties with the continent, and also because of the influence of the City of London as one of the largest financial hubs in the world.

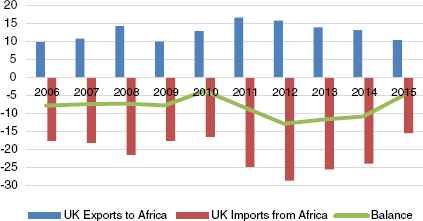

What of the United Kingdom’s existing trading relations with Africa? From the UK’s perspective, Africa is a strategic but in absolute terms not a major trading partner (Fig. 1), representing an identical share of just 2.6% of both imports and exports (IMF, 2017). In 2015, the UK–Africa trade balance sustained a surplus in favour of Africa, of 5.1 billion USD, notwithstanding a marked fall in the value of African exports to the UK between 2012 and 2015, essentially on the back of much weaker commodity prices (raw materials, particularly oil, are the major imports). From the general African perspective too, the UK is a strategically important but still relatively minor market, representing 3.2% of total exports from Sub-Saharan Africa in 2015.6

UK trade with Africa, 2006–2015 (billions USD). Source: IMF DOTs database (accessed June 2017)

A key question is what will happen to these trade flows if and when Brexit is actually implemented. As noted earlier, much depends on the terms of any eventual agreement. Bilateral trade that flows between the UK and the rest of the world will not of course suddenly grind to a halt because of Brexit,7 but it will inevitably lead to a shift in the terms of trade between the UK and the European Union on the one hand, and with countries outside Europe on the other, if and when tariffs are reinstated on the EU–UK trade. This would lead to shifts in both the magnitudes and geographic patterns of trade flows, due to both the changed relationship between the UK and the EU. Indeed, from the perspective of countries outside Europe, the re-imposition of tariffs on trade between the UK and the European Union could paradoxically benefit them through ‘trade diversion’ (Viner, 1950); with less trade between the European Union and the UK, other trading partners potentially stand to gain. That scenario is tested in the simulations in Section 4.

What about the investment links? The UK constitutes an important source of foreign direct investment (FDI) for Africa, with an investment stock that more than doubled over the decade since 2006, rising to 59 billion USD by 2015 (Office for National Statistics, 2016) (Fig. 2). The FDI stock of Africa is estimated to stand at 740.4 billion USD (UNCTAD, 2016), implying that the UK is responsible for approximately 8% of the total. The sectoral composition of UK investment in Africa shows predominance in the mining and financial services sectors. In 2015, mining alone represented more than half (54%) of the investment stock, and financial services approximately a third (33%). With such a large share being motivated by natural resource endowments, it would seem to be a reasonable a priori assumption that such investments in Africa are unlikely to be affected much by Brexit.

UK FDI in Africa, by sector, billions UK pounds 2012–2015.

There are a couple of caveats to this observation; however, were Brexit to lead to a serious deterioration of the British economy, it could constrain the ability of UK-listed companies to raise finance for foreign investments abroad. Similarly, a weak value of sterling is, ceteris paribus, likely to discourage UK direct investments abroad.8 There is no reason, however, to suppose that these factors would specifically impact on Africa.

3. Existing EU–UK trading and investment links with the East African Community

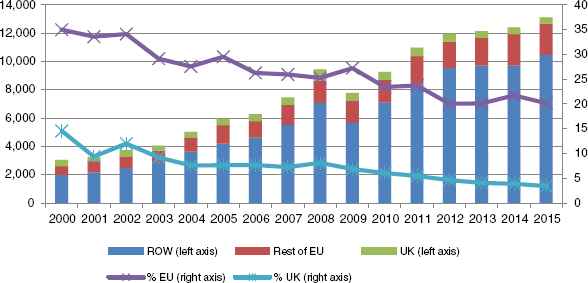

Because of the longstanding historical links, product of their colonial histories, trade and investment links, Europe — and the UK in particular — has maintained strong economic ties with the East African region. However, the intensity of those links has declined in recent years because of the growing importance of South–South trade links — both intra-African trade and trade with emerging markets (particularly China). The EU-27 (i.e., the European Union minus UK), as a destination for EAC exports, has fallen from around 35% of exports in 2000 to just 20% in 2015. The UK has declined as a market for EAC exporters at an even faster pace — going from 14.6 to just 3.4% over the same period (Fig. 3).9 The nominal value of EAC trade towards the UK has also been falling — peaking at 766 million USD in 2008 and declining to just 447 million USD in 2015.

EAC exports to the World, European Union and UK, 2000–15 (millions USD and as a percentage of total). Source: IMF DOTs database (accessed June 2017)

In terms of trading links with individual members of the EAC, it is actually quite surprising how low the UK now ranks, even for Kenya, which retains the strongest ties with the UK, principally through its exports of cut flowers, fresh fruit and vegetables (Mendez-Parra et al., 2016). In 2015, the UK accounted for just 6% of Kenyan exports and 3% of imports (IMF, 2017). Also striking is the fact that Kenya alone makes up around half (1.3 billion USD in 2015) the total of EAC trade towards the EU-28. Thus a lot hinges on what happens to Kenyan exports post-Brexit.10

What about the investment links? In terms of FDI, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda are countries where the UK is a significant stakeholder, being the single leading investor in Kenya, representing approximately 23% of the investment stock, and the second largest investor in Tanzania (21% of the investment stock). In Uganda, British firms account for 10% of the FDI stock, but in the other two landlocked EAC countries Rwanda and Burundi UK investment is negligible.11 Again, the same arguments made in Section 2 hold with regard to FDI flows to the whole of Africa; there is no reason to suppose that significant divestments would take place by British multinationals as a consequence of Brexit. The EAC market has been growing relatively rapidly over the last decade, and a large share of the investments is associated with natural resources (especially in Tanzania and Uganda). Thus the motivations are location-specific and less strongly dependent on conditions in the source-country market.

Finally, an, arguably more minor, channel of ‘contagion’ from Brexit is through remittances. The best estimates that we have for remittances from the United Kingdom suggest that Kenya is the most exposed, with 523 million USD of remittances from the United Kingdom in 2015 (approximately a third of total remittances to Kenya that year), followed by Uganda (283 million USD or approximately a quarter of all remittance inflows) (Table 1). This channel is directly impacted by the devaluation of the sterling, resulting in declines in the value of remittances starting from the second half of 2016. It is also reasonable to assume that remittance flows will be negatively impacted by any negative economic consequences of Brexit on the UK economy itself, particularly if it results in higher rates of unemployment or lower rates of economic activity among migrants. So far, however, this has not been demonstrably the case. In addition, it should be remembered that similar warnings of sharply declining remittances were issued at the time of the global-financial crash — forecasts which did not actually materialise. Indeed, remittances proved to be one of the most resilient cross-border flows (Mohapatra and Ratha, 2010). That may be true also this time.

| Burundi | Kenya | Rwanda | Tanzania | Uganda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From United Kingdom | 0 | 523 | 0 | 69 | 283 |

| From rest of European Union | 5 | 97 | 16 | 19 | 50 |

| From World | 49 | 1561 | 161 | 389 | 1049 |

Estimated remittance flows to the EAC from the UK, the European Union and the World (millions USD, 2015). Source: World Bank Migration and Remittance Database, 2017

4. Simulations of the impact of a ‘hard’ Brexit on the EAC

It is clear from this summary of existing economic links with the European Union that the impact of Brexit is likely to be complex. One approach to making an assessment of multiple impacts is to use a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE). The CGE models use economic data to estimate how an economy or region might react to changes in policy or to external shocks. Using a multi-sector and multi-region framework, a CGE is able to capture interactions between different sectors and markets at both the national and international levels.

The CGE models are not uncontroversial. Because the framework tends to focus on the long run, which often abstracts from short-run realities of structural rigidities in developing countries, such as ‘missing’ or inefficient factor markets, some scholars have argued that they may not be appropriate at all for analysing the problems of the typical developing country (Charlton and Stiglitz, 2004). Most CGE modellers will themselves concede that the simulations provided through CGE modelling should be taken not literally but rather as ‘orders of magnitude’. Nonetheless, CGEs are still widely used because they provide quantitative assessments of policy changes where other methodologies may not be appropriate (Hertel, 1997). In an African context, they have helped highlight important policy issues (e.g., Perez and Karingi, 2007; Fosu and Mold, 2008; Robinson et al., 2012).

Using the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model, simulations are reported in this paper involving a scenario whereby there would be a ‘hard Brexit’ — that is to say, that the UK would not be able to retain duty-free access to the Single Market, and instead would be returned to standard MFN tariffs.12 In passing, from the perspective of trading partners outside the European Union, this scenario should not be excessively alarming — the European Union is a fairly open trading block, with an average trade-weighted tariff of just 2.6% on industrial goods in 2016 — though the figures are significantly higher on agricultural goods, with an average trade-weight tariff calculated at 7.6% (WTO et al., 2018, 81).13 Nevertheless, the imposition of tariffs would inevitably have a significant impact on existing patterns of imports and exports, both within Europe and for other trading partners, not to mention the rise of associated non-tariff barriers. For the service sectors, estimates of the tariff equivalents are utilised, in line with the results from Egger et al. (2015).14

The underlying data in the GTAP 10.0 pre-release database refers to a 2014 baseline. The model is run using a regional aggregation that includes the standard regions included within the GTAP model, plus a distinct EU-27 and UK region, the East Africa Community,15 and a ‘Rest of Africa Region’ (comprising of all the non-EAC African countries). We also separate two major trading partners of the European Union — China and the United States. The sectoral aggregation includes the 10 standard sectors.16 The standard GTAP model assumes perfect competition and constant returns to scale in production (Hertel, 1997). Our study uses a closure that reflects the high levels of un- and under- employment that characterise African labour markets, by fixing wages for both the EAC and the Rest of Africa regions. We also use the standard GTAP savings-driven model where changes in savings rates drive investment. Summary results are shown in Table 2.

| Welfare Millions USD | Terms of trade Millions USD | Terms of trade % Change | GDP % Change | Value of exports % Change | Value of imports % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAC | 156 | 36.4 | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.37 |

| Rest of Africa | 1558 | 899 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.33 |

| UK | − 21,995 | − 12,767 | − 1.86 | − 2.43 | − 4.65 | − 7.75 |

| EU-27 | − 6838 | − 2276 | − 0.03 | − 0.16 | − 0.51 | − 0.63 |

| China | 3144 | 2331 | 0.08 | 0.18 | − 0.01 | 0.26 |

| US | 4759 | 2906 | 0.17 | 0.25 | − 0.16 | 0.42 |

| Middle East | 1464 | 1581 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| Rest of East Asia | 2135 | 1913 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.2 |

| Oceania | 810 | 562 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.43 |

| Rest of South Asia | 872 | 531 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.28 |

| Rest of North America | 657 | 379 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.23 |

| Latin America | 1549 | 1023 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.38 |

| Rest of World | 2760 | 2757 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

Summary results of the simulation.

Source: Author’s Simulation

The first result to highlight is the terms of trade (ToT) impact of the implementation of MFN tariffs on EU–UK trade, as this is perhaps the broadest measure of the trade impacts. Logically, the UK and EU-27 are the economies most adversely affected by Brexit, with ToT losses of −12.8 and − 2.3 billion USD respectively. However, there are also some regions that would benefit from the new export opportunities opened up by the decline in intra UK-EU27 trade. In absolute terms, the United States and China would be the largest beneficiaries, with ToT gains equivalent to more than 4.8 and 3.1 billion USD, respectively, reflecting the more intense trading relations of these countries post-Brexit with the EU-27 and the UK. In relative terms, however, it is interesting to note that the largest gain in ToT is the EAC, equivalent to 0.19% of GDP.

A similar story is revealed in the GDP and welfare impacts (‘Equivalent variation’), the latter of which measures approximately the net benefit/losses to consumers. While the UK loses −2.43% of GDP in static losses from the re-imposition of tariffs, and the European Union a smaller −0.16%,17 the EAC benefits from the increased trading opportunities and price shifts, with a net gain of 0.36% of GDP — that largest relative gain of all the regions identified in the model. Regarding the welfare changes, Brexit translates into USD 22.0 billion of losses for the United Kingdom and USD 6.8 billion for the EU-27 but USD 156 million of benefits for the EAC, and USD 899 million USD for the rest of Africa. These are not large gains in macroeconomic terms, but not insignificant either.

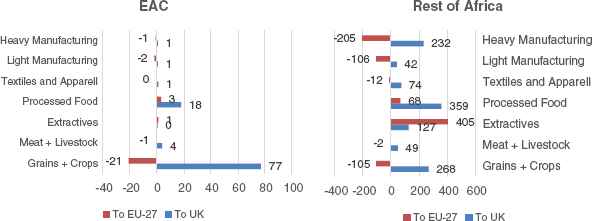

What is driving these changes? Essentially it is a story of trade diversion away from the European market, and towards other trading partners outside Europe, particularly in the sectors more heavily protected by the re-imposition of MFN tariffs on EU–UK trade. For Africa, that essentially means that the greatest opportunities would reside in agricultural products, where existing MFN tariffs are highest. This is apparent in Fig. 4, whereby we see that for the EAC, exports to the UK expand principally in the grains and crop sector. The pattern of post-Brexit trade with the EU-27 and UK is more diverse for the rest of Africa block than in the case of the EAC, due to the greater heterogeneity of economic structure across the whole of the African continent. However, it is notable again that the net gains in trade are largest in the extractive sector, processed food and grains and crops. In other words, outside food processing, it would contribute little to the structural transformation and diversification of African economies.

African exports by sector to UK and EU-27, by sector, post-Brexit (FOB, millions USD). Source: Author’s Simulation

The matrix presented in Table 3 shows the changes in total trade values, with large net losses in trade between the UK and the EU-27. On the other hand, for the EAC a hard Brexit would entail an increase in exports to the UK of USD 115 million, with a small decrease of USD 17 million towards the EU-27, leaving a total increase of exports to Europe of USD 98 million. The rest of Africa would see increases of exports of nearly USD 1.5 billion to both the UK and the EU-27 post-Brexit. It should, however, be noted that Brexit promises to do nothing to improve the continental trade balance. Exports of both the UK and the EU-27 to the African continent would increase by 3.8 billion USD, more than double the expansion of African trade towards Europe.

| Exporting region | Importing region | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAC | Rest of Africa | UK | EU-27 | |

| EAC | − 6 | − 12 | 115 | − 17 |

| Rest of Africa | 0 | − 127 | 1334 | 164 |

| UK | 120 | 1781 | 0 | − 63,731 |

| EU-27 | 57 | 1874 | − 83,560 | 28,791 |

Matrix of changes in trade values, post-Brexit (FOB millions USD).

Source: Author’s Simulation

These changes in trading patterns are also reflected in the output changes estimated by the simulation — for the EAC, grain and crops, meat and livestock would experience the largest increases in output, while there would actually be small declines in textiles and apparel, light and heavy manufacturing (Table 4). These are not exactly desirable consequences from the perspective of diversifying the economies of the EAC, but again, the magnitudes are rather small.

| Value added | Total exports | Total imports | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grains and crops | 0.15 | 1.08 | 0.57 |

| Meat and livestock | 0.11 | 1.41 | 0.73 |

| Extraction | − 0.09 | − 0.18 | − 0.21 |

| Processed food | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.5 |

| Textiles and apparel | − 0.15 | − 0.11 | 0.4 |

| Light manufacturing | − 0.4 | − 0.77 | 0.44 |

| Heavy manufacturing | − 0.43 | − 0.73 | 0.31 |

| Utilities and construction | 0.17 | − 1.06 | 0.7 |

| Transport and communications | 0 | − 0.02 | 0.61 |

| Other services | 0.05 | − 0.16 | 0.58 |

Percentage change in value added, exports and imports for EAC, post-Brexit.

Source: Author’s Simulation

It might moreover be objected that, as a net-food importing region, African countries would not be in a good position to take advantage of these new opportunities in the agricultural sector. Net-food imports for the whole continent reached USD 24.4 billion in 2017.18 However, the fact that countries like Kenya have successfully expanded their horticultural exports over recent decades (Minot and Ngigi, 2010) suggests that there is still scope in the region for expanding export-oriented agricultural production. The issue raises an additional interesting proposition because at the moment we do not know how Brexit will impact on support to farmers in the United Kingdom (or indeed within the EU-27). Under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), British farmers — as is true of their European partners — have been receiving very large subsidies from the EU. In the UK, this amounts to approximately half the income that British farmers currently receive.19 This has been a constant bone of contention for African countries, as the CAP has effectively made entry into the European Union market extremely difficult for African agricultural produce. Akinwumi Adesina, President of the African Development Bank, has recently claimed that “where previously African countries had to deal with the entire European Union on the CAP subsidies that European Union farmers enjoy, Brexit give scope and opportunity for this matter to be renegotiated.” (Adesina, 2017). Ironically, Brexit might represent the first crack in the dam in a set of policies that have impeded African agricultural exports from entering European markets.

5. The indirect consequences of Brexit on the EAC

The objective of the simulations in the previous section was not to prove the case of substantial trading benefits for the EAC from Brexit; the benefits are potentially there but are of rather small magnitude. Rather, the objective was to dispel the idea of a catastrophic outcome from Brexit for Africa in general, and for the EAC in particular. Arguably, the real risks to the region reside elsewhere, in the form of indirect impacts emanating from Brexit. Three major risks and one potential opportunity could be envisaged on the horizon:

5.1. Commitment to overseas assistance in question?

Under the former Prime Minister David Cameron, the British conservative government continued a commitment started under the previous Labour governments to raise overseas development assistance. In 2013 the UK’s aid programme reached, for the first time, the 0.7% of GNI target set out by the United Nations back in the 1970s. Although difficult to measure with precision (because there are both bilateral and multilateral components to the aid flows), around half of that assistance is destined to Africa. The UK is a leading provider of development assistance to the EAC; it is the second largest bilateral donor to the region, providing around 900 million USD a year. This is in addition to the support it provides through multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the European Union itself. The UK is one of the biggest contributors to the European Development Fund, currently contributing £409 million ($585 million), making up 14.8% of contributions to the fund.20

However, judging by various public pronouncements, the UK government is gradually changing its stance on overseas development assistance since the Brexit referendum. The government ministers who lobbied for Brexit have generally been highly critical of the size of the UK’s aid budget, and have challenged how the resources are spent. On arriving in office in July 2016, Prime Minister Theresa May included a number of prominent aid-sceptics in her post-Brexit cabinet — among them, the former head of the British aid agency, Department for International Development (DFID), Priti Patel (who later resigned in November 2017). The former Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson also declared that in the future aid funds will be “more sensibly distributed” to support foreign policy aims such as combating terrorist groups in Africa (Vardy, 2017).

Despite the declared intentions of all EAC member states to reduce their level of aid dependence, it is also still the case that aid-dependency is quite high within the region (Table 5). Tanzania received a total of nearly USD 2.6 billion in 2015, followed closely by Kenya (USD 2.47 billion). In relative terms, Rwanda and Burundi are the most highly aid-dependent countries, both with an ODA to GNI ratio in excess of 10%. In four out of five of the EAC countries, the United Kingdom is the second largest bilateral donor, behind only the United States. This is in addition to the contributions that the UK makes to bilateral institutions such as the World Bank, the EDF, and the AfDB.

| Burundi | Kenya | Rwanda | Tanzania | Uganda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net ODA (million USD) | 367 | 2474 | 1082 | 2581 | 1628 |

| Net ODA (% of GNI) | 11.9 | 3.9 | 13.7 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

| UK’s contribution (millions USD)* | – | 527 | 117 | 280 | 196 |

| Position of UK as bilateral donor | Not ranked | No. 2 behind US (762.3) | No. 2 behind US (179.2) | No. 2 behind US (481.6) | No. 2 behind US (442.8) |

Note: * figures are averages for the years 2014–15.

Aid dependence within the EAC, 2015.

Source: OECD (2016b)

Speculatively, then, in a general political environment in which UK’s strategic interests are defined more narrowly (as suggested by the Boris Johnson quote earlier), Brexit could contribute to undermining the UK’s commitment to overseas development assistance over the longer run. In this context, the EAC is fairly vulnerable. However, as in the case of trade, it is best to temper our judgments. We should not expect a catastrophic reduction; the UK is an important donor, but its bilateral contributions for the region are usually (with the exception of Kenya) between 10 and 15% of all aid inflows, and the UK is highly unlikely to completely renege on its aid commitments to the region. However, against a backdrop where the new US administration has also announced major cutbacks to its aid budget, leveraging foreign assistance to achieve developmental goals is likely to become more challenging for EAC member states over the coming years.

5.2. The negative impact on the global economy of Brexit?

The second indirect risk from Brexit is more diffuse and difficult to quantify, but no less important. Brexit has already been impacting on the global economy, adding an additional layer of economic uncertainty in an already turbulent landscape. It is certainly true that the more pessimistic forecasts emitted prior to Brexit have been shown to be false and excessively alarmist, to the extent that the Bank of England’s Chief Economist has actually even recently apologised for inaccurate forecasts (Giles, 2017). However, the counter-argument is that Brexit has not yet occurred, and that it still represents an enormous risk to the economy once the terms and conditions of Brexit have been agreed and implemented. More difficult to assess still is the impact of Brexit on global markets. With growth forecast by the IMF of nearly 4% for 2018, the world economy is currently very buoyant, but international organisations have been at pains to stress that there are a number of uncertainties that could negatively affect global growth (World Bank, 2017). Certainly, on its own, Brexit would not be enough to destabilise global markets. Other factors, such as fears of a global trade war, currently weigh more heavily on market sentiment (Lagarde, 2018).

How will all this impact on the EAC? Sensitive as they are to fluctuations in commodity prices, African countries generally do not perform well when the global environment is adverse. Brexit has only contributed to generating more uncertainty. That said, it is also true that East Africa has continued to grow rapidly despite the adverse global economic environment since the financial crisis of 2008/9. In addition, unlike some other African sub-regions, East Africa is in fact a net commodity importer, so it is not necessarily adversely affected by declines in commodity prices to the same extent as in other parts of Africa (UNECA, 2017). The best we can say, therefore, is that Brexit adds to the uncertainty in global prospects, and this could damage prospects for trade, investment and development finance.

5.3. A blow to confidence in regional integration?

Perhaps most fundamentally for the EAC, Brexit has arguably dealt a serious blow to confidence in regional integration processes. The European Union has been a long-standing model of integration — not so much for its successes (it has suffered its fair share of set-backs, such as the ERM crisis of the early 1990s, and the Euro-crisis of 2011), but rather for the scale of its ambition. Unlike free-trade deals like the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA), the European Union represents a bold project of political and economic union (what we termed earlier as “deep integration”). In this sense, it is not good for regional integration processes elsewhere if the European project begins to falter.

As noted in the introduction, the EAC is commonly recognised as one of the most ambitious programmes of regional integration in Africa. It contemplates both economic and political union. It also includes, as an integral part of the project, the achievement of monetary union. In terms of the scale and scope of its aspirations, then, the parallels with the European project are clear. Yet there are growing fears within the region with regard to the direction the EAC is taking. A particularly harsh criticism was recently voiced by Maina (2016):

“It is not the thing one says in polite society but, barring a dramatic reset, the East African Community is in a terminal crisis, barely a decade and half since it was re-established… East Africa’s problems are deep-seated: They include a lack of fit between the interests of Kenya and Tanzania; inability to agree on shared values; and a mistaken expansion strategy that favours geographical breadth over institutional depth.”

One does not have to agree fully with this negative assessment to concede that certain parallels can be drawn with some of the fault lines in the recent history of European integration. Nor is it disputable that the EAC could benefit from regaining some of the dynamism that characterised the block in its formative years in the early 2000s. The danger is that the travails of Europe make policymakers in Africa lose enthusiasm for the process of deeper integration. We will elaborate a little more on this point in the conclusions.

5.4. An ‘unravelling’ the economic partnership agreements?

Finally, on a perhaps more positive note from the perspective of some African countries, it has been posited that Brexit could lead to an unravelling of the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) (Stevens and Kennan, 2016). For more than a decade the European Union has been pursuing regional trade deals (EPAs) with African countries to replace its existing preferential agreements, under the alleged grounds that preferential access would no longer be tolerated within the WTO and could be legally challenged. The EPAs were also premised on the basis that they would be negotiated only regionally and would help consolidate regional integration processes in Africa (Mold, 2007). For the EAC, at least, this has not been the case, highlighting the risk that the EPAs can end up pitting countries within regional blocks against themselves (Luke et al., 2017).

Negotiations between the European Union and African regional groups formally started in 2003 and entered what was intended to be the final stage in 2007, with a view to agreements being implemented from 2008 (Morrissey et al., 2007). A decade later, and the EPAs had still not been implemented. As in other regional groupings across Africa, the EPAs have proved to be divisive within the EAC (Ligami, 2017; Luke et al., 2017). The key contentious point has been that Kenya does not benefit from the same preferential access to the European Union market as its other partner countries because it is not classified as a “Least Developed Country”. Kenya thus felt the pressure to sign the EPA because of its dependence on horticultural and flower exports destined to the European Union market (worth in excess of 1 billion USD in 2015). Rwanda and Uganda backed the Kenyan position, but both Burundi and Tanzania dissented. In the former case, the position was tied up with a political dispute, but in the latter, it was based on an objection of a more fundamental nature. Former Tanzanian President Mkapa himself penned an op-ed on the subject, explaining that the implementation of the EPA would be tantamount to undermining the viability of the region’s development plans:

“Tanzania’s position is one of concern for the implications of the region’s drive to industrialisation and the capacity of EAC firms to compete directly with European firms. The EPA is a free trade agreement… Such a high level of liberalisation vis-à-vis a very competitive partner is likely to put our existing local industries in jeopardy and discourage the development of new industries… Regional integration and trade is the most promising avenue for EAC’s industrial development. The EPA would derail us from that promise.”

Cautious, if not openly critical, assessments have come from mainstream sources too. Over a decade ago, World Bank economists Hinkle and Newfarmer (2006, 163) warned, for example, that “a number of important issues will need to be addressed to limit the development risks associated with EPAs. If these issues cannot be satisfactorily resolved, the EPA process could end up being replaced by improved preferences or even abandoned.”

Since their inception, then, the EPAs have generated considerable controversy. In some quarters, the pervading view was that the EPAs were being pursued not primarily because of developmental priorities, or concerns about potential legal challenges through the WTO to existing preferential market access, but rather were intended to address Europe’s rapid loss of market share across Africa, in the face of sustained competition from China and India. The stylized facts provide some support for that view; with regard to total imports to Sub-Saharan Africa, the European Union has experienced a sharp decline in its market share, from around 40% in 2000 to just 23.3% by 2017 — a decline that has been mirrored by the rise of China as a source of imports for SSA (IMF, 2017). For instance, for the EAC, imports from China have increased since 2000 from an insignificant share of total imports (around 1%) to 20% of total imports in 2014 (Mold, 2017). All this puts into context the considerable efforts by the European Commission to finalise the EPAs.

Post-Brexit, however, a key question is whether the EPAs will still be tenable when the UK is no longer part of the block (Stevens and Kennan, 2016). In September 2016, just a few months after the Brexit referendum, this argument was already being used by Tanzania to delay signing the EPA, despite intense pressure from some of its other partner states within the EAC.

At the very least, Brexit may give grounds for the EAC to renegotiate the EPA agreements; though, surely no one is particularly interested in a further prolonged period of negotiations. Like with the Common Agricultural Policy, it opens the possibility that Brexit will lead to a rethink on the part of the European Union of some key elements in its trade, investment and development policies that impact, directly or indirectly, on Africa. In addition, as the UK looks out for new trading opportunities post-Brexit, it may also lead for a more pro-developmental trade policy towards Africa by the United Kingdom. Mendez-Parra et al. (2017) argue that the UK should at the very least apply the principle of ‘do no harm’ and avoid damaging developing countries as it leaves the UK. They encourage the UK to adopt a simpler, more predictable, transparent and realistic trade policy, looking for ‘win–win’ options, such as more liberal rules of origin, preferential access in services and Aid for Trade.

6. Conclusions

This paper has shown that Brexit will create challenges for the East African Community — but not necessarily in the way that is commonly thought. It is not going to lead to a sharp reduction in trading or investment links; indeed, on this score, the simulation results reported in this paper suggest that there is some reason to expect a more positive outcome, with some additional trading opportunities opening up on the margin (though regrettably not in the kind of diversified products that most African countries wish to export). All the analysis in this paper is of course contingent on both on the final terms of Brexit, and the subsequent trade, investment and developmental policy adopted by both the UK and the EU-27 members. On that of course, the verdict is still out. Some are optimistic that it could pave the way to a more pro-developmental stance. For instance, according to Boateng (2016), Brexit presents both Africa and the UK with an opportunity to “put development at the heart of our trading relationship with Africa in a way frankly that it has not always been in relation to the EPAs, let’s be frank about it.”

Regardless of these potentially positive outcomes, this paper has argued that Brexit may still represent a serious challenge to the onward march of regional integration processes in Africa. For the EAC, one of the most advanced regional economic communities in Africa, the message is particularly poignant and also one of the most ambitious. Implicitly, if not explicitly, the European Union has been an important role model for the EAC, yet that role model is now wobbling.

Another important message emanating from the analysis in this paper is that, regardless of the outcome of Brexit, African countries can no longer depend on external trading relations to help reach their developmental goals. Even if there is a hard Brexit, which generates new trade opportunities on the margin for some African countries, our analysis suggests that they will be neither that large in magnitude nor pro-developmental; instead, they would incentivize greater specialisation in undiversified commodities and agriculture.

Against such a backdrop, and at a time of great global uncertainty and waning faith in the global trading system and multilateralism, it is logical, as Fosu and Ogunleye (2018:35) acknowledge, that African countries will adopt growth strategies that are more regionally inward-looking and self-reliant in their conceptualization. The signing in March 2018 in Kigali of the AfCFTA by no less than 44 member states of the African Union reflects how strongly embedded this realisation is.

The underlying logic is compelling. For the EAC member states, the African market is already their most important market. For Uganda, average figures for 2015–17 from UNCTAD (2018) show that over 51% of the country’s exports are intra-African, and for Kenya and Rwanda the equivalent figures are 39% and 31%, respectively. Most external assessments agree that over the last decade the EAC has clearly benefited from greater intra-regional trade, investment and migration.21 However, the implementation of the AfCFTA promises to provide a new impetus to regional integration processes like the EAC (Mold, 2018). Collectively, then, the economies of the EAC, and Africa generally, are stronger. The correct response at a time like this is not to doubt, but rather to redouble efforts towards regional integration, while learning the pertinent lessons from Europe.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the participants at the Meeting of the Economic Affairs Sub-Committee of the Macroeconomic Affairs Committee, East African Community, Zanzibar, Tanzania 30th January to 3rd February 2017, for their valuable comments and feedback on an earlier draft of the paper. He would also like to thank the Editor of the Journal of Africa Trade Professor Augustin Fosu and an anonymous reviewer for their comments and suggestions as to how to improve the paper. Additional helpful comments were provided by Professor Rajneesh Narula, Dr. Rodgers Mukwaya, Dr. Pedro Martins, Dr. Abdoulaye Ibrahim Djido and Wait Kit Si Tou. Any errors that remain are the sole responsibility of the author.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Afreximbank.

Three of the five countries (Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya) were former colonies of the United Kingdom. If the newest member of the EAC is counted (South Sudan), four of the six countries are ex-colonies of the UK. Burundi and Rwanda were Belgian colonies.

There have been various historical precedents to the current East African Community, starting in colonial times with a currency board arrangement during the time of the East Africa Protectorate, a Customs Union between Kenya and Uganda in 1917, later joined by Tanganyika later in 1927; the East African High Commission (1948–1961); and the first manifestation of the East African Community (1967–1977).

Article 5 (2) of the EAC Treaty states that “The Partner undertake to establish among themselves a Customs Union, a Common Market, subsequently a Monetary Union and ultimately a Political Federation”

Analysis carried out by the HM Treasury (2016), IMF (2016) and OECD (2016a) prior to the referendum came to a wide range of possible outcomes for the UK, dependent upon the agreed degree of market access under the new arrangements. Long-run impacts were estimated at between −1 and 8% of GDP. Emerson et al. (2017) provide a more recent summary of some of the existing studies.

The AfCFTA was inaugurated in March 2018 at the African Union Summit held in Kigali, and 49 out of 55 African member states are now signatories (including all six member states of the East Africa Community).

The level of importance differs across countries, with African countries like Kenya and Mauritius having stronger trade ties (Mendez-Parra et al., 2016).

This is however the assumption of some observers, who point out that once the United Kingdom is out of the European Union, it would have to renegotiate hundreds of trade deals, and that Africa would probably be at the bottom of the queue in terms of its overall priority. These arguments however assume that no provisional arrangements will be put in place in the intervening period — arguably, an unlikely state of affairs.

There is some academic debate over this proposition. In principle, a weaker sterling exchange rate makes assets denominated in foreign currencies more expensive, and so would discourage further FDI. But a lower exchange rate also makes repatriated profits more valuable in pounds sterling. For a summary of research on this matter, see Dunning and Lunda (2008).

Absolute values of EAC trade with Europe have still been rising. The EU-27 received approximately 2.6 billion USD of EAC exports in 2015, considerably up from the 1.1 billion USD in 2000. However, that trade has not kept up with the dynamism apparent in the relations with other trading partners, and hence the share has declined over time.

In the worst-case Brexit scenario of being returned to standard Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) tariffs, Kennan (2016: Table 1) calculates that an extra 18.3 million US dollars of duties, equivalent to around 5% of total exports, would be liable on Kenyan exports to the UK.

Figures come from the most recently available national investment surveys for the respective EAC member states.

Simple average MFN applied tariffs were used for the simulation, as reported by WTO et al. (2018).

The GTAP database already includes the preferential rates under which most African countries export to the European Union market. The simulation is made with the assumption that there are no changes with regard to post-Brexit EU-27 and UK trading arrangements with extra-EU trading partners. It has been a matter of extended discussion what those terms may be. See the collected volume by Mendez-Parra et al. (2016).

Based on a gravity model, Egger et al. (2015) calculates the ad valorem cost saving equivalents of being part of the European Union for different economic sectors.

Burundi could not be included as there is no underlying data in the GTAP database at present. However, because Burundi represents just 1.8% of the regional economy, it is unlikely that its exclusion would impact significantly on the results. South Sudan was not considered in the analysis.

The sectors are: Grains and Crops, Meat and Livestock, Extraction, Processed food, Textiles and Apparel, Light Manufacturing, Heavy Manufacturing, Utilities and Construction, Transport and Communications, and Other Services.

The asymmetric nature of the losses, with the UK losing far more than the EU-27 from the mutual imposition of MFN tariffs, is to be expected in theoretical terms, and is replicated in other studies. See Emerson et al. (2017; page 29).

Calculated from UNCTAD (2018) data.

For an overview of the reformed CAP and its developmental implications, see Mathews (2011).

It should be noted that this is more or less in line with the UK’s share of European Union GDP. The UK is also the number-one funder of IDA17 (the concessional borrowing window at the World Bank) with about a 13.2% share.

For example, a recent assessment (Allard et al., 2016) of the depth of integration in global value chains of Sub-Saharan economies argues that EAC countries are “among the best performers, progress within the EAC has been particularly strong.”

References

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Andrew Mold PY - 2018 DA - 2018/11/27 TI - The consequences of Brexit for Africa: The case of the East African Community☆ JO - Journal of African Trade SP - 1 EP - 17 VL - 5 IS - 1-2 SN - 2214-8523 UR - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joat.2018.10.001 DO - 10.1016/j.joat.2018.10.001 ID - Mold2018 ER -