Adherence to Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis Guideline in Medicine Unit at Soba University Hospital: A Descriptive Retrospective Study

, Bashir A. Yousef3, *,

, Bashir A. Yousef3, *,

- DOI

- 10.2991/dsahmj.k.210624.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Acid-suppressive therapy; guidelines; Soba University Hospital; stress ulcer prophylaxis

- Abstract

Although several guidelines for Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis (SUP) have been published, Acid-Suppressive Therapy (AST) remains largely prescribed in hospitalized patients. Thus, our study aimed to evaluate the current practice surrounding SUP in Soba University Hospital (Khartoum, Sudan). This descriptive cross-sectional hospital-based retrospective study was conducted in the medicine unit of Soba University Hospital. The sample size was 317 participants, and data were collected from medical records from January to December 2018 using a validated checklist. SPSS was applied for data analysis. The mean age of patients was 53 ± 16.8 years, and 170 (54%) of them were female. The mean duration of hospital stay was 10 ± 7.4 days. Seventy-four percent of patients who received prophylaxis did not have an indication for SUP. The majority (116; 36.5%) of patients who were administered parenteral drugs can tolerate oral medications. Overall, the dose of acid-suppressant drugs was optimal in all patients. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs), especially pantoprazole, are the dominant AST used (314; 99.1%). Moreover, 315 (99.4%) of the study population were taking medication during hospitalization and two (1%) patients were discharged with AST. The study concluded that SUP was administered to noncritically ill hospitalized patients who lacked or had few risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding. PPIs were the overwhelming choice among practitioners. Collectively, the study showed low adherence to guidelines when prescribing (AST) outside critical care settings. Therefore, there is an urgent need for implementation of practical guidelines in noncritical care settings.

- Copyright

- © 2021 Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Stress ulcers are defined as single or multiple defects on the gastrointestinal mucosa that can lead to various clinical manifestations, scaled from mild to severe ulceration, or may cause life-threatening bleeding [1]. Clinically, the risk of stress ulcers increases in hepatized patients, particularly if the patient is admitted to intensive care settings [1]. Reports indicated that 75–100% of critically ill patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) had endoscopic evidence of Stress-related Mucosal Disease (SRMD) [2]. Although such mucosal erosions may cause mild clinical manifestations owing to the rapid healing process, they should be managed to avoid the risk of bleeding [3]. Many etiological factors may be related to development of SRMD including reduction in mucosal blood flow, or interruption of normal mucosal defense mechanisms combined with the harmful effects of acid on the gastrointestinal mucosa [4]. As acid is clearly associated with the pathogenesis of these mucosal erosions, acid-suppressive medications have therefore a potential role in SRMD prevention [2,5].

In the literature, several consensus guidelines for Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis (SUP) have been documented [6–8]. According to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) guidelines, SUP is not recommended in noncritically ill patients or those with fewer than two risk factors for clinically significant bleeding. Meanwhile, for ICU patients, SUP is recommended if the patient has coagulopathy; has a history of gastrointestinal ulceration; is bleeding within 1 year prior to admission; requires mechanical ventilation for more than 48 h; or has at least two of the following risk factors: more than 1 week stay in the ICU, sepsis, occult bleeding lasting 6 days or more, and high-dose corticosteroids usage [7,9]. Recently, Acid-Suppressive Therapy (AST) has been largely prescribed in hospitalized patients [10,11]. Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs) and Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) are the common AST agents that have been prescribed prophylactically to prevent complications in the gastrointestinal tract [12,13]. However, inappropriate prescription and overutilization of AST agents may cause a set of risks and long-term complications including pneumonia and Clostridium difficile infection [14,15]. Several published studies have revealed that inappropriate or overused prescriptions of AST agents in the hospital setting may consequently result in substantial cost expenditures without beneficial impact on care quality [16–20].

According to the ASHP guidelines, SUP is not recommended for general medical and surgical patients in non-ICU settings with no major risk factor or fewer than two minor risk factors. However, it is observed that in Sudanese hospitals there is improper prescription and overutilization of AST agents. Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the current practice of SUP in Soba University Hospital.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A descriptive cross-sectional hospital-based retrospective study was performed in the medicine unit of Soba University Hospital, Khartoum state, Sudan. The study population consisted of patients admitted to the medicine unit at Soba University Hospital from January to December 2018.

2.2. Participants and Study Size

The medical records of patients admitted to the medicine unit of Soba Hospital from January to December 2018 were collected. A simple random sampling technique was used to select the patients’ files in the department of statistics. Epi info 7.1 software (Centers for Disease Control; Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for the randomized selection of patients’ file numbers to avoid risk of bias. The total number of patients admitted to the medicine unit from January to December 2018 was 1530 (medical records). The calculated sample size was 317 medical records measured using Solvin’s equation: n = N/(1 + Ne2), where N is the total target population attending the center, n is the sample size, and e is the margin of error (0.05) at the 95% confidence level [21].

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

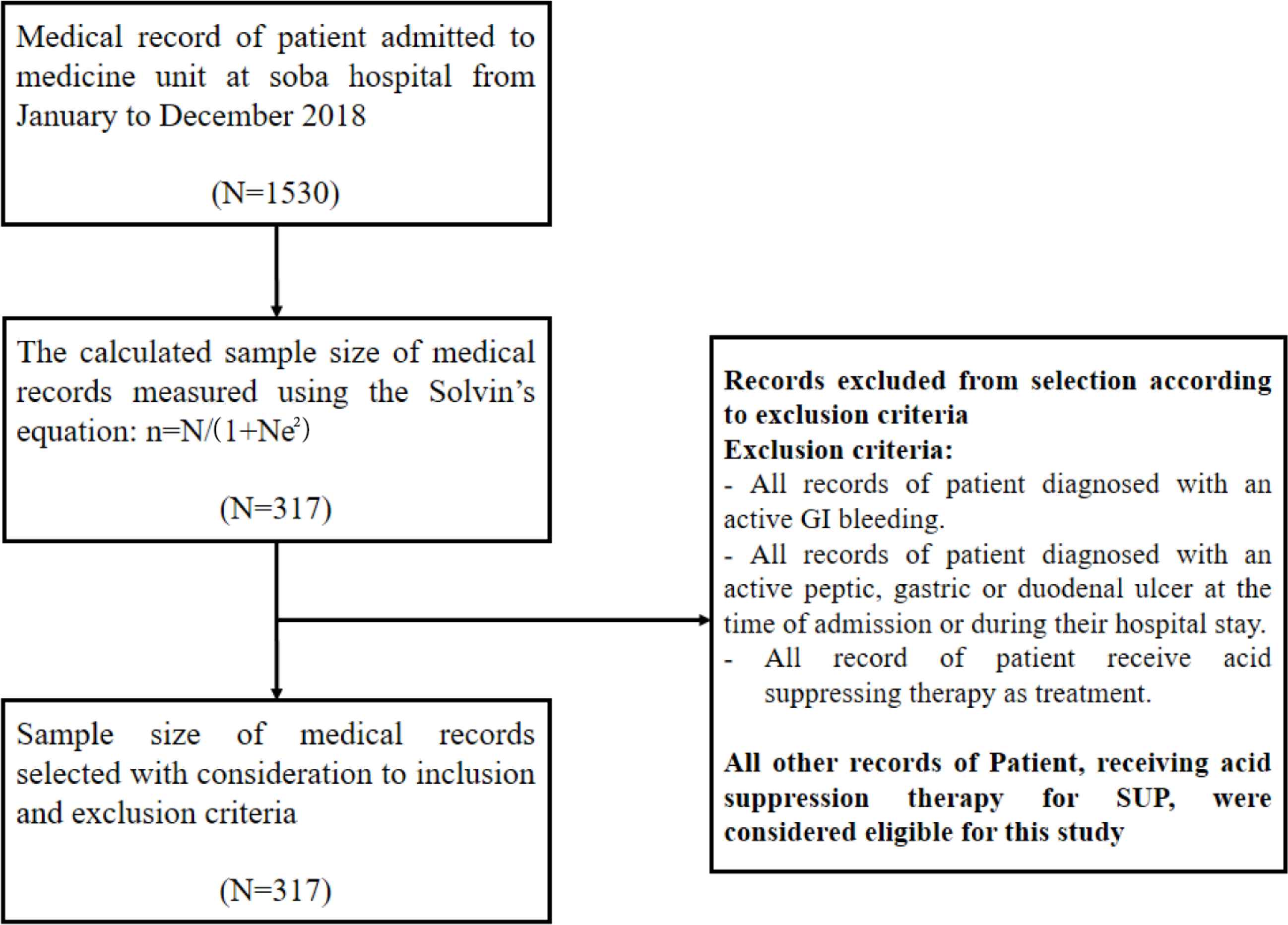

Records of patients admitted to the medicine unit at Soba University Hospital during the study period were included in the study. However, all records of patients diagnosed with an active gastrointestinal bleeding, active peptic, gastric ulcer, or duodenal ulcer at the time of admission or during their hospital stay, and all records of patients who received acid-suppressing therapy as treatment were excluded (Figure 1).

Flowchart showing recruitment of participants into the study. GI, gastrointestinal.

2.4. Variables

Medical records were reviewed, and the following data were extracted: disease state, SUP regimen, stress ulcer risk factors.

2.5. Data Sources/measurements

A predesigned checklist was used as a data collection form, and it consisted of patient’s demographics including general characteristics of the patients such as age, sex, and length of hospital stay. The second part focused on disease state, which included chief complaint and diagnosis. These data are crucial to determine the eligibility of patients for the study. The third part deals with SUP regimen (drugs used, dose, route, and duration) to allow the assessment of SUP appropriateness. The fourth part is about stress ulcers risk factors. A stress ulcer risk stratification, adopted from the ASHP guidelines, divided patients into three categories: noncritically ill medical patients, ICU populations, and pediatrics. The recommendation for prophylaxis was based on the risk factors for clinically important bleeding. According to the ASHP guidelines, SUP is not recommended for noncritically ill patients with fewer than two risk factors for clinically significant bleeding.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequency tables) and inferential statistics (Chi-square test, independent sample t-test, and binary logistic regression test) were used. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant in comparative data.

2.7. Ethical Consideration

The ethical clearance (FPEC-11-2019) was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Khartoum. Additional approval was taken from the administration of Soba University Hospital prior to starting data collection. All data were encoded to sustain confidentiality throughout the study.

3. RESULTS

Overall, 22.4% of the study population (n = 317) was between 61 and 70 years old, and the mean patient age was 53 ± 16.8 years. Moreover, 170 (53.6%) of patients were females. Regarding the length of hospital stay, the median length of stay was 8 (interquartile range, 5–13) days, and 29% of the participants stayed in the hospital for 4–6 days (Table 1). The records also showed that 116 (36.6%) had cardiovascular diseases, and 60 patients were diagnosed with ischemic stroke (Table 1).

| Demographic and clinical data | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 18–30 | 42 (13.2) |

| 31–40 | 38 (12) |

| 41–50 | 67 (21.1) |

| 51–60 | 69 (21.8) |

| 61–70 | 71 (22.4) |

| 71–80 | 25 (7.9) |

| 81–90 | 5 (1.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 146 (46) |

| Female | 171 (54) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | |

| 2–3 | 34 (10.7) |

| 4–6 | 92 (29) |

| 7–9 | 59 (18.6) |

| 10–12 | 47 (14.8) |

| 13–15 | 39 (12.3) |

| 16–20 | 26 (8.2) |

| >21 | 20 (6.3) |

| Final clinical diagnosis | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 116 (36.6) |

| Infection disease | 61 (19.2) |

| Hepatic disease | 20 (6.3) |

| Renal disease | 45 (14.2) |

| Metabolic disease | 60 (18.9) |

| Neurological disease | 12 (3.8) |

| Other disease | 3 (0.9) |

Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics and disease state among the study sample (n = 317)

Regarding SUP regimens, the study showed that among 317 patients 314 (99%) received pantoprazole 40 mg single dose per day (OD) and only three (1%) patients received ranitidine 150 mg twice/daily which in Latin means twice a day, and there was no use of other agents for SUP (Table 2). All doses used by patients in this study were corrected according to ASHP guidelines and recommendations. The appropriateness of the administration route was determined according to the oral intake of the patients; if a patient can tolerate oral medications, then that person should take AST by oral route [7]. Thus, among 317 patients who received AST, 122 (38.5%) received medications by the oral route and 195 (61.5%) by the parenteral route. Moreover, records also showed that 315 (99.4%) patients were taking medications during hospitalization, and two (0.6%) patients were discharged with acid-suppressing therapy (Table 2).

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Agent use for SUP (dose) | |

| Pantoprazole 40 mg (OD) | 314 (99.1) |

| Ranitidine 150 mg (BID) | 3 (0.9) |

| Route of administration of SUP regimen and their appropriateness | |

| Oral | 122 (38.5) |

| Appropriate | 119 (97.5) |

| Not appropriate | 3 (2.5) |

| Parenteral | 195 (61.5) |

| Appropriate | 79 (40.5) |

| Not appropriate | 116 (59.5) |

| Duration of treatment with SUP regimen | |

| During hospitalization only | 314 (99) |

| Discharged with it | 3 (1) |

Various variables (type of drug used, route of administration, duration) of Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis (SUP) regimens

After determination of risk factors for each patient, the SUP indication was classified as either appropriate or inappropriate according to the ASHP guidelines. Among 317 patients who received AST, 233 (73.5%) did not have an indication for SUP according to ASHP guidelines; this total included 149 (47.2%) noncritically ill patients and 84 (26.4%) patients who had one minor risk factor. By contrast, 84 (26.5%) patients had risk factors that make them appropriate for indication: 75 (23.7%) patients had one major risk factor (coagulopathy was the most frequent, at 57.5%) and nine (2.8%) patients had two minor risk factors (Table 3).

| Stress ulcers risk factors | n (%)* |

|---|---|

| Noncritically ill medical and surgical patients | 149 (47.2) |

| One minor risk factor | 84 (26.4) |

| Sepsis | 12 (14.2) |

| ICU stay longer than 1 week | 5 (5.9) |

| Occult bleeding | 1 (1.2) |

| High doses of corticosteroid | 13 (15.5) |

| Chronic use of NSAID/high dose of aspirin | 53 (63.1) |

| Critically ill patients | 84 (26.4) |

| One major risk factor | 75 (23.7) |

| Coagulopathy (i.e., platelet count of <50,000 mm3, INR of 1.5) | 43 (57.3) |

| Mechanical ventilation for >48 h | 7 (9.3) |

| History of GIT ulceration or bleeding within 1 year of admission | 9 (12) |

| Partial hepatoectomy | 2 (2.7) |

| Hepatic or renal transplantation | 2 (2.7) |

| Hepatic failure | 5 (6.7) |

| Coagulopathy + hepatic failure | 5 (6.7) |

| Coagulopathy + mechanical ventilation for >48 h | 2 (2.7) |

| Two minor risk factors | 9 (2.8) |

| ICU stay of greater than 1 week + chronic NSAID/high dose of aspirin use | 2 (22.3) |

| Sepsis + chronic NSAID/high dose of aspirin use | 2 (22.3) |

| Sepsis + high-dose corticosteroids > 250 mg/day of hydrocortisone or equivalent daily) | 4 (44.5) |

| High-dose corticosteroids >250 mg/day of hydrocortisone or equivalent daily) + chronic NSAID/high dose of aspirin use | 1 (11.2) |

| Appropriateness of indication according to the number of risk factors | |

| Appropriate | 84 (26.5) |

| Non-appropriate | 233 (73.5) |

No significance is observed here.

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; INR, international normalized ratio; GIT, gastrointestinal tract.

Assessment of stress ulcer prophylaxis risk factors

Chi-square test was used to analyze the practice pattern of SUP with each component of the AST (drug class, dose, route, and duration). There was a statistically significant association (p = 0.005) between sex and indication, in that 42.9% of patients with appropriate indications were females. Furthermore, the administration route was significantly associated with the indication’s appropriateness; in parenteral, the indication was more appropriate than the oral form (p = 0.001). Moreover, a significant association was also detected between final diagnosis and indication results (p = 0.001), in that the percentage of inappropriate indication was higher in patients with cardiovascular disease (26.8%) and infectious disease (17%).

When an independent sample t-test was performed to compare the mean age among risk factors for ulcer (critically and noncritically ill patients), we found that there was no significant association between mean age among the two groups (p = 0.259). Furthermore, the Mann–Whitney U-test showed that the mean rank of hospital stay among critically ill patients was higher compared with that of noncritically ill ones (p = 0.029). When a Chi-square test was performed to determine the association between risk factors (critically ill patients and noncritically ill patients), we found that sex, route of administration, and indication had a statistically significant association with risk factors among participants (p = 0.014, p = 0.044, and p < 0.001), respectively.

When a logistic regression test was performed to determine the predictors for patients’ risk factors, as shown in Table 4, we found that females were more likely to be critically ill than males by two times [p = 0.025; 95% Confidence Interval (CI), 1.09–3.763]. Logically, the parenteral route of administration was more likely to be used than the oral route in critically ill patients by 1.6 times (Table 4). Interestingly, patients with hepatic disease were more likely to be critically ill than patients with renal diseases by eight times [p = 0.002; odds ratio (OR) = 8.4; 95% CI, 2.220–31.650) (Table 5).

| Variables | Risk factors | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noncritically ill medical and surgical patient, n (%) | Critically ill patient, n (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.014 | ||

| Male | 108 (73.9) | 38 (26.1) | |

| Female | 102 (59.5) | 69 (40.5) | |

| Indications | 0.000 | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 67 (57.6) | 49 (42.4) | |

| Hepatic disease | 4 (20.0) | 16 (80.0) | |

| Infectious disease | 52 (85.7) | 9 (14.3) | |

| Metabolic disease | 53 (88.3) | 7 (11.7) | |

| Neurological diseases | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Renal diseases | 31 (68..9) | 14 (31.1) | |

| Others | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Route of administration | 0.044 | ||

| Parenteral route | 122 (62.6) | 73 (37.6) | |

| Oral route | 91 (74.6) | 31 (25.4) | |

The association between the risk factors (critically and noncritically ill patients) with other variables (n = 317)

| Variables | B | SE | Sig. | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sex | 0.707 | 0.315 | 0.025 | 2.028 | 1.093 | 3.763 |

| Hospital stay | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.061 | 1.037 | 0.998 | 1.077 |

| Route of administration | 0.446 | 0.333 | 0.181 | 1.562 | 0.813 | 3.000 |

| Indications | 2.126 | 0.678 | 0.002 | 8.382 | 2.220 | 31.650 |

| Constant | –1.815 | 0.481 | 0.000 | 0.163 | – | – |

OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; Sig., significance.

Predicting patient’s risk factors using binary logistic regression test (n = 317)

4. DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the real ulcer prophylaxis (SUP) practice in 317 patients in the medicine unit of Soba University Hospital. According to ASHP guidelines for SUP, only 26% of admitted patients received the appropriate prophylaxis, whereas 74% received inappropriate acid-suppressive medications. In effect, 47.2% of the inappropriate indications were for noncritically ill medical and surgical patients. The role of SUP in noncritically ill patients at the non-ICU setting was previously reported in an American tertiary care center, which revealed the needless use of prophylactic AST in hospitalized patients [18]. Moreover, another study reported the economic cost of such practices, indicating that they increased the cost expenditures without enhancing the quality of care [20]. Thus, our findings further support the recommendations for constructing clear risk factors in the non-ICU setting to use SUP.

Proton pump inhibitors and H2RAs drugs are still unnecessarily prescribed and overused in hospitals to prevent stress ulcers in healthcare settings [22–25]. In the current study, 314 (99.1%) of patients received pantoprazole (PPI), whereas only three (0.9%) patients received ranitidine. These findings are in contrast to another study in which H2RAs are the most commonly used drugs for SUP [26]. However, in recent years PPIs have become clinicians’ first choice for SUP [27], as PPIs provided clinically better outcome in preventing gastrointestinal bleeding when compared with H2RAs without increasing the risk of pneumonia [28]. Nevertheless, use of PPIs in hospitalized patients significantly increased the risk of SUP-related C. difficile infections compared with H2RAs [13,29]. Furthermore, Buendgens et al. [30] revealed that no differences were observed in prevention of gastrointestinal hemorrhage despite the use of PPIs or H2RAs. Similarly, other reports found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding between these agents [27,31].

Regarding the route of administration of AST, it was inappropriately prescribed in the majority of patients. Owing to the physician’s misconception about the superior effectiveness of parenteral dosage form, in this study 36.5% of patients who could tolerate the oral dosage form received parenteral ones. Therefore, our study also recommends using only the parenteral dosage form for patients who cannot tolerate oral drugs. Consequently, reduction of potential side effects and excessive costs will be achieved [32]. However, the mean hospital stay was 10 days, and AST agents were used throughout the hospitalization period even upon removal of risk factors. This practice is also inadequate, as ASHP guidelines recommend stopping AST medications upon removal of risk factors or discharge from the hospital [7], because long-term use of AST drugs may be associated with adverse effects and increase in cost [33].

In the assessment of duration of SUP therapy in critically ill patients, a previous report showed that 357 critically ill ICU patients received AST to treat SUP. Following transfer from ICU, 80% of these patients continued on AST. However, 60% of the therapy was inappropriate, and 24.4% was attributed to an inappropriate prescription after discharge from the hospital [34].

This study is not without limitations. Because it was conducted at a single unit in Soba University Hospital, the result cannot be generalized to all hospital units or other hospitals. Therefore, these findings need be validated by a large study across Sudanese hospitals. Missing data are another limitation in this study. Despite this limitation, however, the findings of this study are interesting and new because it is the first of its kind to be conducted in Sudan. In addition, it sheds light on the current practice of SUP in Sudanese hospitals and highlights the need for the implementation of guidelines for SUP.

5. CONCLUSION

Stress ulcer prophylaxis was administered to noncritically ill hospitalized patients who had no or few risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding. PPIs were the overwhelming choice among practitioners. Collectively, the study showed low adherence to guidelines when prescribing AST outside the critical care setting.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AAE developed the design and definition of the intellectual content, performed the data collection and acquisition. SB performed the analytic calculations and performed the data analysis. AAE and SB contributed to the final version of the manuscript. BAY supervised the project, designed the study, determined the concept, prepared and edited the final manuscript.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Alaa A. Elmubarak AU - Safaa Badi AU - Bashir A. Yousef PY - 2021 DA - 2021/06/29 TI - Adherence to Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis Guideline in Medicine Unit at Soba University Hospital: A Descriptive Retrospective Study JO - Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Journal SP - 125 EP - 130 VL - 3 IS - 3 SN - 2590-3349 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/dsahmj.k.210624.001 DO - 10.2991/dsahmj.k.210624.001 ID - Elmubarak2021 ER -