Self-medication Practices and Knowledge among Lebanese Population: A Cross-sectional Study

, Batoul Diab, Dalia Khachman*,

, Batoul Diab, Dalia Khachman*,  , Rouba K. Zeidan

, Rouba K. Zeidan , Helene Slim, Salam Zein

, Helene Slim, Salam Zein , Amal Al-Hajje, Jinan Kresht, Souheir Ballout, Samar Rachidi

, Amal Al-Hajje, Jinan Kresht, Souheir Ballout, Samar Rachidi- DOI

- 10.2991/dsahmj.k.200507.002How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Community pharmacy; knowledge; Lebanon; practice; self-medication

- Abstract

Self-medication (SM), practiced globally, is an important public health problem. This is the first study aiming to determine the prevalence of inappropriate usage of drugs among Lebanese patients, assess their knowledge, and identify predicting factors of potentially inappropriate drug intake. This cross-sectional prospective survey was carried out in five Lebanese governorates. A structured interview was done with patients who visited pharmacies. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A multivariate logistic regression was performed to investigate factors associated with SM, which was reported by 79.1% of 930 interviewed cases. The most common symptoms warranting SM were symptoms relating to ear, nose, and throat diseases (99.0%), gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea and vomiting (75.6%), and cold and flu symptoms (60.1%). Age [adjusted odds ratio (ORa) = 1.44; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.15–1.80; p = 0.002] and sex (ORa = 1.60; CI, 1.16–2.21; p = 0.004) significantly increased the odds of SM. Medication classes commonly consumed by respondents for SM included acetaminophen-based analgesics (48.7%) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (24.6%). Moreover, 83.7% of respondents thought they were knowledgeable about proper dosing of the self-medicated drug (in fact, only 69.0% had adequate knowledge), and 35.5% thought they knew about side effects (assessment showed only 59.5% of them were right). Our study shows that SM is common among Lebanese adults. Hence, reinforcement of laws is necessary to improve access to adequate health care; efforts are needed to increase patients’ education regarding the health risk related to inappropriate consumption of medication.

- Copyright

- © 2020 Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Medications represent an important remedy for most illnesses, and they ensure the amelioration of the quality of life of patients. However, inappropriate intake of these substances may be associated with health risks. Practicing Self-medication (SM) is troublesome because of the facilitated access to therapeutic drugs leading to potential risks on health [1]. Regulations generally differentiate between two drug categories. The first is prescription-only, which requires a medical prescription for these medications to be dispensed; the second group includes Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, which are easier to access for SM for uncomplicated and treatable medical cases. Despite this distinction, numerous patients tend to self-medicate regardless of the type of drug listed—that is, even prescription-only medications are somehow accessible for them without a prescription [2].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), SM is the “selection and use of pharmaceutical or medicinal products by the consumer to treat self-recognized disorders or symptoms, the intermittent or continued use of a medication previously prescribed by a physician for chronic or recurring disease or symptom, or the use of medication recommended by lay sources or health workers not entitled to prescribe medicine” [3]. The main sources of SM are relatives, friends, or pharmacists who not only provide medicines but also information about the use of these drugs [4]. Moreover, several factors—such as lack of access to health care, physician fees, time constraint, lack of trust in physicians, and inadequate implementation of drug laws—been shown to influence SM behavior [5].

Self-medication is commonly practiced in both developed and developing countries, but it is more common in the latter [6,7]. Drug misuse in the Middle East can be mainly attributed to the fact that prescription-only medications are dispensed without prescriptions [2]. Even though the SM issue had been covered in several studies, it has not yet received the attention it deserves; limited information has been available on its main determinants, particularly in developing countries. In fact, most studies on SM have been conducted in developed countries whose health care systems are dissimilar to ours in Lebanon.

To study what the population knows about a specific condition, how people behave in relation to it, and the factors affecting it, studies on knowledge and practices have been conducted worldwide. No studies performed in Lebanon have focused on the knowledge and practices related to use of medicines despite a high rate of SM, which has not yet been documented [8]. Thus, the objectives of our study were to (1) evaluate the knowledge and practices concerning medication, (2) identify the reasons for SM, (3) check the sources of information about medication, and (4) identify the potential factors that could influence SM practices among Lebanese patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design and Study Population

This cross-sectional prospective study was conducted in a community-based pharmacy setting in Lebanon. During a 4-month period (February–June 2018), data were collected from Community Pharmacies (CPs) distributed in the five governorates of Lebanon: Beirut, South Lebanon, Mount Lebanon, Bekaa, and North Lebanon. Eligible participants were patients attending CPs who were interviewed face to face. The participants consisted of males and females aged 18 years or older visiting the pharmacies to get their medicines. Participants were distributed among two groups: those who practice SM versus those who do not. A voluntary informed consent was required for enrollment in the study.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size (N) calculation was performed using the formula: N = 4P(1 − P)/Precision2. The reference prevalence of SM “P” was taken as 87% as reported in a similar study conducted in Palestine [9]; the precision was fixed at 0.03. This gave us a minimum sample size of 503 patients.

2.3. Data Collection

The study questionnaire was formulated in the official language (Arabic) and included four sections of 22 open-ended and four close-ended questions. For validation, it was pretested on 40 patients attending five pharmacies prior to the actual beginning of the study. This was to ensure that the questionnaire was fully comprehensible to the public. Data were collected by trained pharmacists who had been taught about the objectives and methods of the study. The first section of the questionnaire included questions on sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, occupation, educational and marital status, employment status, salary, insurance, and lifestyle habits). The second section targeted information about the medical history of respondents, their chronic diseases, and the background medication. Respondents were also asked whether they practiced SM. The third section, which was exclusively applied to those who practiced SM, contained questions about respondents’ reasons for SM, the pathological cause or symptoms inciting SM, and the source of information regarding their drug of choice. In the final section, the respondents who self-medicated were requested to answer questions examining their knowledge regarding the dosing regimen and side effects of one of the drugs used as an SM.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data entry and analysis were performed using SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Respondents were grouped into patients practicing SM and those who are not (Yes/No). Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies and percentages of knowledge and practices. Chi-square test was done to check the differences between these two groups regarding their sociodemographic characteristics. A logistic regression analysis was performed to check for confounding variables and to calculate the odds ratios (OR) for independent ones for SM. Significance level was attained at p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 930 adult patients were surveyed, of whom 52.2% were females. They were mainly young with a mean age of 37.5 ± 15.2 years (range, 18–82 years). The most common educational level was completion of elementary and high school education (49.0%). Among participants, 79.1% practiced SM, whereas 194 (20.9%) did not (Table 1).

| Characteristic | All participants (N = 930) | Not practicing self-medication (N = 194) | Practicing self-medication (N = 736) | p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percentage (%) | N | Percentage (%) | N | Percentage (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 442 | 47.5 | 112 | 25.3 | 330 | 74.7 | |

| Female | 488 | 52.5 | 82 | 16.8 | 406 | 83.2 | |

| Age class (years) | 0.003 | ||||||

| 18–39 | 510 | 54.8 | 88 | 17.3 | 422 | 82.7 | |

| 39–60 | 321 | 34.5 | 75 | 23.4 | 246 | 76.6 | |

| ≥60 | 99 | 10.7 | 31 | 31.3 | 68 | 68.7 | |

| Marital status | 0.23 | ||||||

| Single | 414 | 44.5 | 79 | 19.1 | 335 | 80.9 | |

| Married | 464 | 49.9 | 100 | 21.6 | 364 | 78.4 | |

| Widowed or divorced | 52 | 5.6 | 15 | 28.8 | 37 | 71.2 | |

| Region | 0.078 | ||||||

| Beirut | 475 | 51.1 | 93 | 19.6 | 382 | 80.4 | |

| North Lebanon | 21 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 100.0 | |

| South Lebanon | 257 | 27.6 | 56 | 21.8 | 201 | 78.2 | |

| Bekaa | 41 | 4.4 | 10 | 24.4 | 31 | 75.6 | |

| Mount Lebanon | 136 | 14.6 | 35 | 25.7 | 101 | 74.3 | |

| Educational level | 0.055 | ||||||

| Illiterate | 43 | 4.6 | 8 | 18.6 | 35 | 81.4 | |

| Elementary–High school | 456 | 49.0 | 110 | 24.1 | 346 | 75.9 | |

| University degree | 431 | 46.4 | 76 | 17.6 | 355 | 82.4 | |

| Work status | 0.701 | ||||||

| Private sector employee | 278 | 29.8 | 59 | 21.2 | 219 | 78.8 | |

| State or public employee | 166 | 17.8 | 37 | 22.3 | 129 | 77.7 | |

| Self-employed | 142 | 15.3 | 32 | 22.5 | 110 | 77.5 | |

| Unemployed | 68 | 7.4 | 17 | 25.0 | 51 | 75.0 | |

| Housewife | 155 | 16.7 | 26 | 16.8 | 129 | 83.2 | |

| Student | 121 | 13.0 | 23 | 19.0 | 98 | 81.0 | |

| Salary range (USD) | 0.742 | ||||||

| 0–500 | 386 | 41.5 | 76 | 19.7 | 310 | 80.3 | |

| 500–1000 | 186 | 20.0 | 42 | 22.6 | 144 | 77.4 | |

| 1000–1500 | 208 | 22.4 | 47 | 22.6 | 161 | 77.4 | |

| ≥1500 | 150 | 16.1 | 29 | 19.3 | 121 | 80.7 | |

| Insurance | 0.049 | ||||||

| No | 69 | 7.4 | 8 | 11.6 | 61 | 88.4 | |

| Yes | 861 | 92.6 | 186 | 21.6 | 675 | 78.4 | |

| Type of insurance | 0.439 | ||||||

| NSSC | 642 | 70.9 | 123 | 20.6 | 474 | 79.4 | |

| Private insurance | 223 | 24.6 | 55 | 24.7 | 168 | 75.3 | |

| Military health care insurance | 40 | 4.5 | 8 | 20.0 | 32 | 80.0 | |

| Exercising | 0.199 | ||||||

| No | 494 | 53.1 | 111 | 22.5 | 383 | 77.5 | |

| Yes | 436 | 46.9 | 83 | 19.0 | 353 | 81.0 | |

| Smoking status | 0.147 | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 389 | 41.8 | 90 | 23.1 | 299 | 76.9 | |

| Smoker | 541 | 58.2 | 104 | 19.2 | 437 | 80.8 | |

| Alcohol | 0.592 | ||||||

| No | 515 | 55.4 | 103 | 20.0 | 412 | 80.0 | |

| Yes | 380 | 40.8 | 85 | 22.4 | 295 | 77.6 | |

| Occasionally | 35 | 3.8 | 6 | 17.1 | 29 | 82.9 | |

| Chronic diseases | 0.679 | ||||||

| No | 694 | 74.6 | 147 | 21.2 | 547 | 78.8 | |

| Yes | 236 | 25.4 | 47 | 19.9 | 189 | 80 | |

| Number of pathologies | 0.973 | ||||||

| 1 | 197 | 83.8 | 41 | 20.8 | 156 | 79.2 | |

| ≥2 | 38 | 16.2 | 8 | 21.6 | 30 | 78.4 | |

The p values obtained by Chi-square for categorical variable. All p values ≤0.2 are shown in bold.

Characteristics of the study population

The characteristics of the study population and their SM behavior are illustrated in Table 1. The results show that SM was significantly more prevalent in females than in males (83.2% vs. 74.7%; p = 0.001). Similarly, young individuals (p = 0.003), and those with a university degree (p = 0.055) were more likely to administer SM than their counterparts. Finally, lack of insurance also appeared to be significantly related to SM practice (p = 0.049).

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

To check for the association between independent variables (sociodemographic and health-related factors) and the dependent variable (SM practice), we conducted a backward binary logistic regression, with all variables with p ≤ 0.2 as the independent variables (see Table 1). Two variables show a significant association with the dependent variable: age [adjusted Odds Ratio (ORa) = 1.44; p = 0.002; 95% Confidence Interval (CI), 1.15–1.80] and sex (ORa = 1.60; p = 0.004; 95% CI, 1.16–2.21). However, lack of insurance was shown to be a trend that might have an effect on SM in the future (ORa = 2.09; p = 0.057; 95% CI, 0.98–4.48) (Table 2).

| Independent variables | ORa | 95% Confidence interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age class | 1.44 | 1.15 | 1.80 | 0.002 |

| Sex | 1.60 | 1.16 | 2.21 | 0.004 |

| Lack of insurance | 2.09 | 0.98 | 4.48 | 0.057 |

Logistic regression backward stepwise likelihood ratio; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.040; p-value for Hosmer–Lemeshow test = 0.960; p-value of the omnibus test was <0.001.

Unretained variables: region, educational level, smoking status, and exercising.

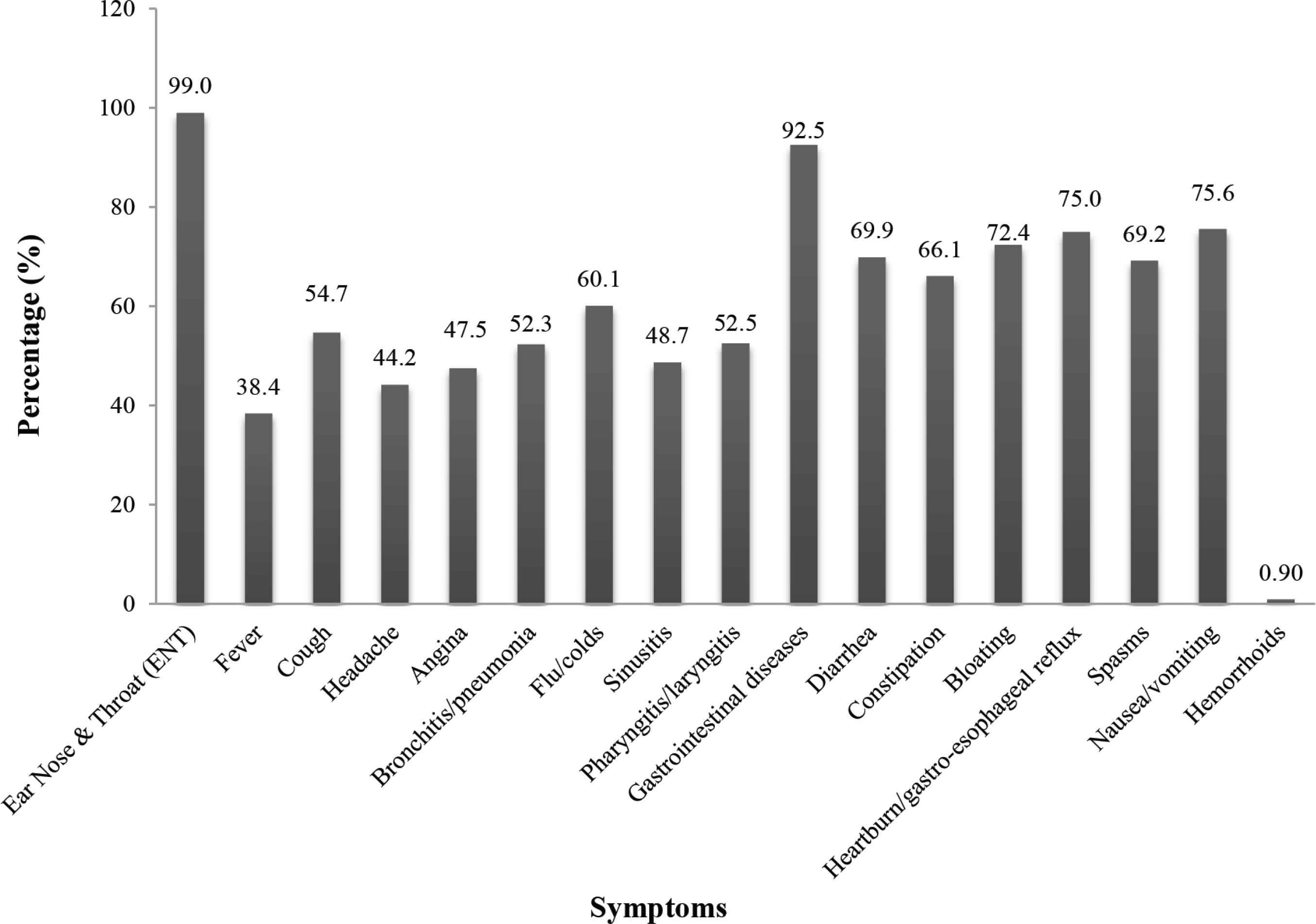

3.3. Self-medication Practices among Participants

Figure 1 shows that the most common indications for SM were associated with ENT (99.0%) and Gastrointestinal (GI; 92.5%) diseases. Our study showed a high percentage of nonprescribed obtainment of medicines to treat Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) illnesses (99%), including flu/colds (60.1%), followed by cough (54.7%), and pharyngitis/laryngitis (52.5%). As for GI diseases, the most common symptoms subjected to SM were nausea/vomiting (75.6%), heartburn/gastroesophageal reflux (75.0%), bloating (72.4%), and diarrhea (69.9%). In addition, SM was commonly practiced for lower respiratory tract infections such as bronchitis/pneumonia (52.3%).

Symptoms warranting self-medication. Results are given in percentage. Numbers do not add up to 100% as patients might practice self-medication for several illnesses.

The classes of medicines commonly purchased by participants for SM were acetaminophen-based analgesics (48.7%), Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) (24.6%), and antibiotics (8.8%). Moreover, the study identified patients’ reasons for SM: the most common reason was that their illness was mild (45.1%). More than one-quarter of respondents (26.1%) indicated that they self-medicated because they had tried the same medication previously and it was beneficial; 11.4% of self-medicated patients clarified that they did not have enough time to visit health care facilities. Some cited monetary constraints as the reason behind their SM (11.4%). Another reason for SM was that a friend/relative was knowledgeable about the treatment for their conditions (6.0%; Table 3).

| N | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Classes of medicine used by respondents for self-medication | ||

| NSAIDs | 184 | 24.6 |

| Antibiotics | 66 | 8.80 |

| Antispasmodic drugs | 38 | 5.10 |

| Sinusitis medications | 2 | 0.30 |

| Acetaminophen-based analgesics | 364 | 48.7 |

| GIT medicine | 53 | 7.10 |

| Antiallergic medicine | 17 | 2.30 |

| Vitamins | 23 | 3.10 |

| Total | 747 | 100.0 |

| Reason for practicing self-medication | ||

| Mild illness | 332 | 45.1 |

| Lack of time | 84 | 11.4 |

| Monetary constraints | 84 | 11.4 |

| According to the advice of a friend/relative | 44 | 6.00 |

| Previous good experience with the drug | 192 | 26.1 |

| Total | 736 | 100.0 |

| Source helping in deciding which drug to use | ||

| Empty package of drug | 136 | 18.6 |

| Former prescription | 174 | 23.8 |

| Pharmacist’s advice | 270 | 36.9 |

| Physician’s advice | 128 | 17.5 |

| Others’ advice | 23 | 3.20 |

| Total | 731 | 100.0 |

| Source of information of drugs for self-medication | ||

| Pharmacist | 357 | 48.5 |

| Physician | 91 | 12.4 |

| Package leaflet | 217 | 29.5 |

| Scientific book or journal | 8 | 1.10 |

| Internet | 8 | 1.10 |

| Other | 55 | 7.50 |

| Total | 736 | 100.0 |

GIT, gastrointestinal tract; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Practices related to self-medication

Factors affecting the choice of medication were examined. Most respondents followed a pharmacist’s advice (36.9%) or a physician’s advice (17.5%). Others admitted their choice was based on a former prescription (23.8%) or on an empty package of drug found at home (18.6%). Patients who practiced SM were asked about the source of information for their medicines. The most common source was local pharmacists (48.5%), followed by medicinal leaflets (29.5%) and physicians (12.4%). The least common source of information was scientific books or journals, and the Internet (1.1% each; Table 3).

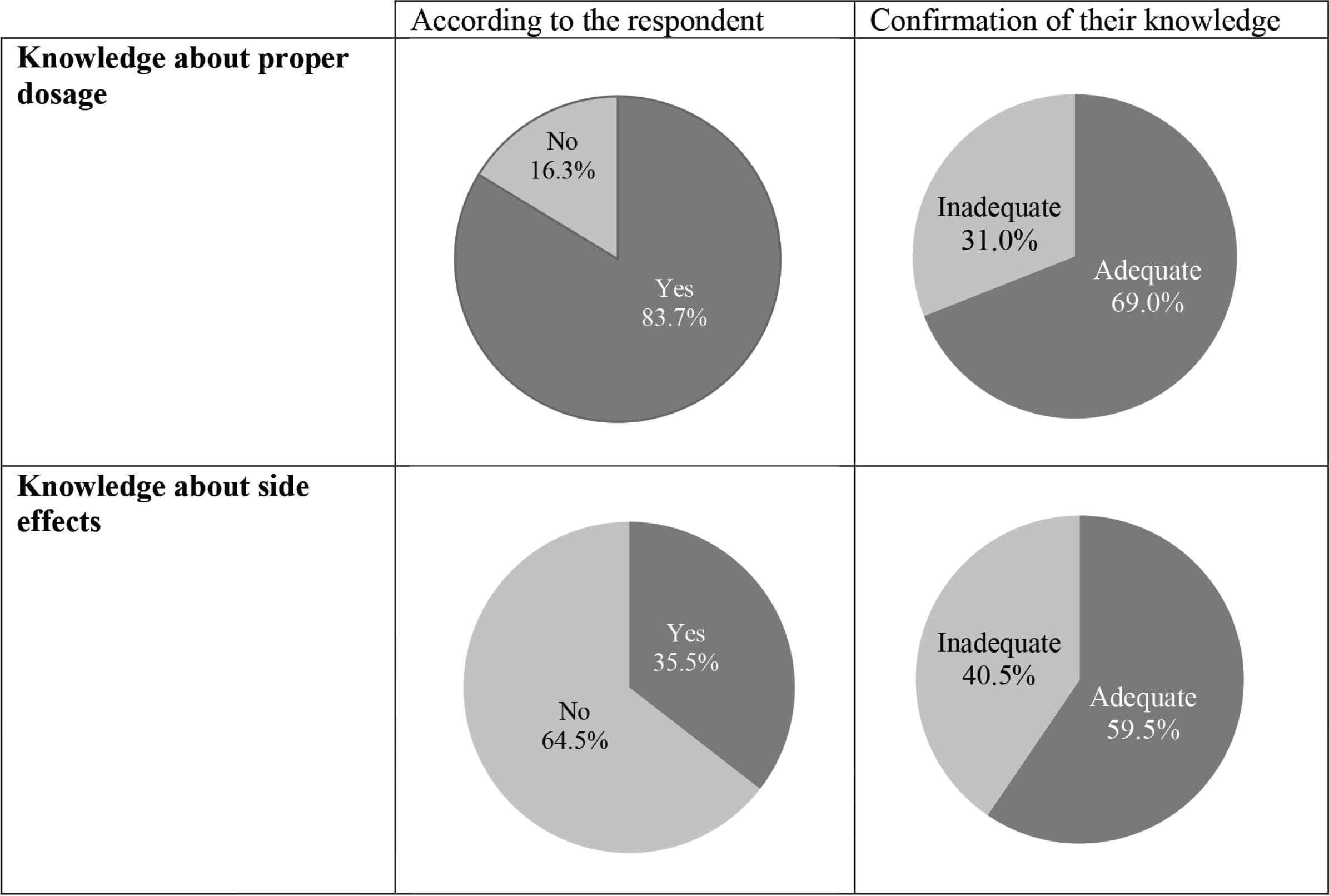

As shown in Figure 2, the knowledge assessment revealed that although 83.7% of the respondents thought they were knowledgeable about proper dosing regimen, only 69.0% of them had an adequate knowledge. Moreover, although 35.5% thought they were knowledgeable about side effects, it was later confirmed that 40.5% of them had inadequate knowledge. A significant relationship was found between some sociodemographic characteristics of respondents and their medicinal knowledge. In fact, younger age and those who attended university had the highest levels of adequate knowledge regarding the proper dosage regimen (74.2% and 74.4%, respectively) as well as side effects (67.6% and 65.9%, respectively). The knowledge about side effects was also found to be significantly associated with marital status, work status, and source of information (Table 4).

Medical knowledge of respondents.

| Knowledge about proper dosage, N(%) | Knowledge about side effects, N(%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate knowledge | Inadequate knowledge | p* | Adequate knowledge | Inadequate knowledge | p* | |

| Age class (years) | 0.004 | 0.001 | ||||

| 18–39 | 271 (74.2) | 94 (25.8) | 115 (67.6) | 55 (32.4) | ||

| 39–60 | 126 (61.5) | 79 (38.5) | 38 (45.8) | 45 (54.2) | ||

| ≥60 | 31 (63.3) | 18 (36.7) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | ||

| Marital status | 0.136 | 0.003 | ||||

| Single | 216 (73.0) | 80 (27.0) | 92 (69.2) | 41 (30.8) | ||

| Married | 195 (65.9) | 101 (34.1) | 60 (48.4) | 64 (51.6) | ||

| Widowed or divorced | 17 (63.0) | 10 (37.0) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | ||

| Education level | 0.020 | 0.015 | ||||

| Illiterate | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | ||

| Elementary–High school | 191 (63.9) | 108 (36.1) | 46 (49.5) | 47 (50.5) | ||

| University studies | 224 (74.4) | 77 (25.6) | 110 (65.9) | 57 (34.1) | ||

| Work status | 0.097 | 0.001 | ||||

| Private sector employee | 137 (69.2) | 61 (30.8) | 63 (67.0) | 31 (33.0) | ||

| State or public employee | 76 (71.7) | 30 (28.3) | 19 (39.6) | 29 (60.4) | ||

| Self-employed | 59 (64.8) | 32 (35.2) | 18 (46.2) | 21 (53.8) | ||

| Unemployed | 30 (71.4) | 12 (28.6) | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Housewife | 59 (60.2) | 39 (39.8) | 14 (45.2) | 17 (54.8) | ||

| Student | 67 (79.8) | 17 (20.2) | 36 (80.0) | 9 (20.0) | ||

| Insurance | 0.709 | 0.066 | ||||

| No | 30 (66.7) | 15 (33.3) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | ||

| Yes | 398 (69.3) | 176 (30.7) | 152 (60.8) | 98 (39.2) | ||

| Source of information of drugs for self-medication | 0.678 | 0.035 | ||||

| Pharmacist | 197 (68.6) | 90 (31.4) | 43 (69.4) | 19 (30.6) | ||

| Physician | 57 (72.2) | 22 (27.8) | 20 (71.4) | 8 (28.6) | ||

| Package leaflet | 132 (71.0) | 54 (29.0) | 79 (57.2) | 59 (42.8) | ||

| Scientific book or journal | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Internet | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Other | 32 (62.7) | 19 (37.3) | 12 (38.7) | 19 (61.3) | ||

Statistically significant results are shown in bold. p value detected by Pearson Chi-square test.

Assessment of medicinal knowledge in patients practicing self-medication

4. DISCUSSION

The study has shown a high rate of SM (79.1%), which was similar to the results of a study conducted among emergency departments of French academic hospitals, which showed that 84.4% admitted doing SM [10]. Our results indicate Lebanese women’s willingness to self-medicate; this affirms the results of several studies [11–13], but contradicts others [14,15]. Similarly, younger respondents were using SM more often than their older counterparts, which comes in concordance with the results of other studies [12–14]. Moreover, participants who were not insured were at risk of self-medicating. The misdistribution of health facilities and the accompanying increase in health care costs, which lead to the failure of a health care system, have been mentioned as a factor in SM [16]. It was also found that patients who have difficulty accessing health care services have a higher probability of becoming frequent users of SM in resolving their health problems [17]. SM is thus a phenomenon with vast social implications, especially in a developing country such as Lebanon where low income rates result in a high proportion of the population having trouble accessing the health care system. These results agreed with those of a Lebanese study showing a higher rate of antibiotic dispensation without a prescription in lower socioeconomic areas [18]. The educational level of participants appeared to be a significant factor in the bivariate analysis. Those with a university degree were more prone to self-medicate, as observed in other studies [19,20]; nevertheless, it was excluded from the logistic regression model, and this was also observed in a previous study [14].

Almost all self-medicators used SM for ailments associated with ENT and GI diseases, in concordance with the results of another study [15]. The most commonly self-medicated ENT illness was flu/cold; this has also been observed in several studies including a Spanish study, which found that 45% of cold and influenza treatments consumed by the population involve SM [16], and a study conducted by Badiger et al. [15], which revealed that 69% of conditions prompting SM were common colds. As for GI diseases, the most common symptoms subjected to SM were found to be nausea/vomiting, heartburn/gastroesophageal reflux, bloating, and diarrhea. This trend was similar to that seen in a Belgian study where the most dominant GI symptoms were burning retrosternal discomfort followed by acid regurgitation and bothersome postprandial fullness [21]. However, our results differ from a previous South Indian study that showed that the most reported GI symptoms were diarrhea (23%), gastritis (21%), and nausea/vomiting (16%) [15].

Concerning the families of drugs frequently taken by participants for SM, acetaminophen-based analgesics came in first place, NSAIDs second, followed by antibiotics. This trend resembles the findings of a Palestinian study, in which analgesics including NSAIDs (79.2%), followed by flu medication (45.3%), and antibiotics (33.0%) were the most common classes of drugs used in SM [9].

However, our results differ from those of an Indian study, which showed that antipyretic (71%), acetaminophen-based analgesics (65%), antihistamines (37%), and antibiotics (34%) were the drug classes that were frequently used [15]. In fact, it is well known that acetaminophen-based analgesics are the most commonly used OTC class of drugs for SM [22,23], as the most frequent symptom for which drugs, without a medical prescription, are sought is pain [11,23]. This was followed by NSAIDs, which are a matter of concern because of their GI, cardiovascular, hepatic, and renal complications [24,25]. Moreover, attention should be focused on the antibiotic SM values reported in our study, because inadequate consumption of antibiotics could result in antibiotic resistance, one of the public health concerns particularly in developing countries [26].

The current study also identified patients’ reasons for SM. The most commonly cited factor is mild illness, as found in the study of Al-Ramahi [9]. In fact, it is generally acknowledged that SM has a significant role in the management of minor ailments [11,27]. Nearly one-quarter of respondents indicated that they self-medicated because they had already used the same medicine in the past and it was beneficial, whereas others self-medicated because they simply did not have enough time to visit health care facilities or because of consultation costs. Such reasons are consistent with those previously reported in different studies [9,14].

Only 6% of the participants admitted that the reason why they self-medicated was that a friend or a relative recommended the drug. Our observations are comparable with those obtained in a study conducted in Chile, where only 6.4% of SM used was recommended by a family member and 4.1% by friends [11], but are in contrast with the results from a study performed by Badiger et al. [15], who found that 38% of medical students used their senior/classmates as sources of information of SM.

We then examined the factors that influenced the choice of the drug used. In most cases, respondents followed a pharmacist’s advice (36.7%), whereas 17.4% based their decision on a physician’s advice. Thus, we noticed that pharmacies have enabled SM, and have been acting as medication prescribers. This outcome is in line with other studies from neighboring countries including Saudi Arabia [14], Egypt [28], and Palestine [9]. Others admitted that their choice was based on an old prescription (23.6%) or on an empty package of medication found at home (18.5%). Indeed, multiple indications highlighted an association between SM and stocks of drugs at home [29], which could represent a risk source, especially if they are of a tight therapeutic margin, are expired, or could be accessed by children [30].

The most common source of information found in our sample was local pharmacists, reported by about half of the respondents, highlighting the utmost importance of pharmacists in minimizing SM risk within this population. This was followed by medicine leaflets, which should give information about the process itself; however, they could be misunderstood depending on the discrepancy between the reading level of the leaflet and the reading and comprehension skills of the patient. As a matter of fact, in our results, only 57.2% of those who thought themselves knowledgeable and using the leaflet as a source of information had an accurate knowledge about the side effects versus 32.6% of the examined group in India who were ignorant about the adverse effects of the drugs they used [15]; meanwhile, in a study conducted by Farah et al. [31], 76% of the respondents knew the side effects of using unprescribed drugs. Next, came those who have physicians as a source of information (12.4%); this small percentage is to be expected, because a lot of people think that doctors do not recommend SM [32], as many believe that doctors are usually reluctant to give patients advice on SM without a clinical examination.

The lesser used sources of information include scientific books or journals and the Internet. Other sources of information (7.5%), which are probably unreliable ones, include relatives, friends, and the media, and people can readily be misled by these sources [33]. SM can be risky if used by poorly informed people. The knowledge regarding drugs used needs to be assessed, because of the variable level of patients’ knowledge regarding their medications [34]. The knowledge assessment revealed that 83.7% and 35.5% of the respondents thought they were knowledgeable about proper dosing regimen and side effects, respectively, when in fact only 69.0% and 59.5% of them had an adequate knowledge. This constitutes an alarming finding, which shows that patients overestimate their knowledge about proper dosage. Moreover, this reveals that the overall population is not sufficiently experienced for practicing responsible SM, contrary to the WHO-advocated approach [35].

Our results showed that the medicine knowledge of respondents was significantly affected by some sociodemographic characteristics. In fact, younger people and those who attended university had the highest levels of adequate knowledge regarding the proper dosing regimen and the side effects of certain drugs. Knowledge about side effects was also found to be significantly associated with marital status, work status, and source of information. Concerning the latter, the highest percentage of accurate knowledge of adverse effects was found in scientific books or journals. Other sources were physicians followed by pharmacists, whereas the most likely source of misinformation was the Internet. Again, this finding highlights the importance of the community pharmacists’ role, especially in view of their convenient position in the community to aid and guide a safe and efficient utilization of medicines, especially in the case of self-medicators [35].

Multiple limitations should be considered when interpreting the outcome of this study. First, the results of our study were obtained from self-reported data; hence, they may be subjective and respondents may be reluctant to answer truthfully questions relating to self-medicated utilization of certain drugs, because of the sociocultural habits that surround the consumption of certain drugs. Second, a recall bias might occur because no recall period was fixed, which may lead to a greater imprecision (especially underestimation) of prevalence estimates [36], and decreases the accuracy of recall. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the aim of this study was not to measure the prevalence of SM; had this been the case, a fixed recall period would have been mandatory. In fact, in cross-sectional studies, a prolonged recording period may be required in order to make the period more representative, especially when day-to-day variation is marked. However, this may be countervailed by less accurate reporting. Therefore, recall accuracy and representativeness ought to be well balanced. Another possible shortcoming may be that our sample was relatively young, possibly explaining the low chronic diseases rate found. This may have led to the underestimation of the effect of comorbid diseases on the practice of SM as several studies have shown a correlation between these two factors [14,20].

5. CONCLUSION

Our study represents a significant step forward in understanding the SM practices among Lebanese patients. The present study demonstrated a high level of SM practices but inadequate medicine knowledge among respondents. Hence, remedial actions are necessary to promote appropriate SM by making sure that patients are given adequate information about the hazards posed by SM by encouraging them to seek information regarding the drug they intend to use—not from the Internet, but from physicians or pharmacists instead. Encouraging physicians or pharmacists to take part in this process is necessary to give clearer instructions to their patients, especially elderly patients, married patients, and those with a low educational level. This study shows a need for authorities to make existing laws regarding drugs more stringent; it should also encourage policymakers to be more responsive to ensure that people can adequately access health care.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

SA and SR contributed in study conceptualization. RKZ and HS contributed in data curation. BD, RKZ, HS and SB contributed in formal analysis; SA, AAH and SR contributed in funding acquisition. SA, SZ and AAH contributed in methodology. SA and SR contributed in project administration. SA, SR, SB and DK contributed in supervision. RKZ, HS, SA and BD contributed in writing (original draft) the manuscript. SA, BD, DK and JK contributed in writing (review and editing) the manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the

ABBREVIATIONS

- CI,

confidence interval;

- CP,

community pharmacy;

- ENT,

ear, nose and throat;

- GI,

gastro-intestinal;

- NSAIDs,

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

- OR,

odds ratio;

- OTC,

over-the-counter;

- SM,

self-medication;

- SPSS,

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences;

- WHO,

World Health Organization.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Sanaa Awada AU - Batoul Diab AU - Dalia Khachman AU - Rouba K. Zeidan AU - Helene Slim AU - Salam Zein AU - Amal Al-Hajje AU - Jinan Kresht AU - Souheir Ballout AU - Samar Rachidi PY - 2020 DA - 2020/05/11 TI - Self-medication Practices and Knowledge among Lebanese Population: A Cross-sectional Study JO - Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Journal SP - 56 EP - 64 VL - 2 IS - 2 SN - 2590-3349 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/dsahmj.k.200507.002 DO - 10.2991/dsahmj.k.200507.002 ID - Awada2020 ER -