Awareness of Lebanese Pharmacists towards the Use and Misuse of Gabapentinoids and Tramadol: A Cross-sectional Survey

These authors contributed equally to this work.

- DOI

- 10.2991/dsahmj.k.200206.002How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Gabapentinoids; knowledge; Lebanon; misuse; pharmacists; tramadol

- Abstract

Community pharmacists are the most accessible healthcare professionals. Recently, the increasing trend of tramadol and gabapentinoids prescription has become a global problem, with a high risk of misuse and abuse. This study mainly assessed the knowledge and practice of Lebanese pharmacists regarding the use of gabapentinoids and tramadol, and also identified the predictors of knowledge. A cross-sectional survey was conducted on a sample of 295 Lebanese community pharmacists over a period of 4 months. Data were collected using a questionnaire filled online by the participants. Knowledge scores for tramadol and gabapentinoids together and for each separately were computed and dichotomized into poor and good knowledge. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean scores of tramadol and gabapentinoids knowledge individually were 18 ± 7 and 18 ± 6, respectively; 52.9% and 52.5% had good knowledge, whereas 47.1% and 47.5% had poor knowledge concerning these drugs, respectively. Moreover, it was observed that having a master’s degree increases knowledge about tramadol and gabapentinoids by approximately two times. Regarding pharmacists’ practice concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids dispensing, 97.6% and 71.5% of pharmacists, respectively, do not dispense them without prescription. About 43% of pharmacists believe that current governmental regulations are not adequate to control the problem of misuse, with 86.8% citing the need for new laws and better supervision on such drugs to limit their misuse. This study highlighted that pharmacists’ knowledge concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids needs to be improved, reflecting the importance of enrolling pharmacists in continuous learning system.

- Copyright

- © 2020 Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Pharmacists serve as an essential part of our healthcare system. The role of community pharmacists has recently evolved, beyond dispensing medication, toward the enhancement of patient care and pharmacist–patient interaction. Their knowledge of patients’ medical history and thus, identifying drug interactions and dosing schedules, plays an important role in limiting dangerous and fatal drug interactions. Pharmacists taking this path promise to consider the interest toward their patients and community, by applying knowledge, experience, and skills to provide the best outcomes for patients [1].

Although medications are mainly intended to heal patients and treat them, many have harmful consequences when they are misused. Pharmacists do not have the right to prescribe controlled drugs themselves; they can only dispense them if a doctor’s prescription is shown.

Tramadol was classified as a Schedule III controlled drug in June 2014, because of its increased use and possibility of misuse, which may lead to dangerous harms [2]. In addition, gabapentinoids, which include pregabalin and gabapentin only, have been widely used worldwide in recent years, revealing several potential side effects [3].

In Lebanon, community pharmacies are the most accessible primary healthcare facilities. By the end of 2017, Lebanon had 3174 community pharmacies with a ratio of 6.48 pharmacies per 10,000 inhabitants [4]. Community pharmacies are privately owned, and they are the only legal provider of prescription and nonprescription drugs to patients. Concerning gabapentinoids and tramadol dispensing in Lebanon, both must be dispensed with a doctor’s prescription. Tramadol dispense records are placed in a book that is inspected by the Ministry of Public Health every year. However, in the case of gabapentinoids, there are no clear regulations that control their dispensing.

Tramadol, a weak agonist at the µ-opioid receptor and a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1995 for the treatment of moderate to severe pain in adults [1]. Clinical studies have shown that tramadol is effective in reducing pain associated with neuropathy, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and low back pain [5]. Given its multimodal properties, tramadol is also prescribed off-label to treat a broad range of conditions such as opioid withdrawal, postoperative shivering, premature ejaculation, as well as depressive and anxiety disorders. In contrast to other opioids, tramadol has a lower risk of constipation, respiratory depression, overdose, and addiction [6]. However, it has specific risks atypical to the standard opioid class of medications, owing to the inhibition of monoamines reuptake. These adverse effects include seizures, serotonin syndrome, tachycardia, hypertension, and reports of mania activation [7].

Regarding gabapentinoids, both gabapentin and pregabalin have structures that are similar to gamma-aminobutyric acid. They are known as inhibitors of alpha-2-gamma subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channels in the Central Nervous System (CNS), predominantly located in the presynaptic membranes, preventing postsynaptic excitability and neuronal overexcitation, as well as sensitization [8]. Both are licensed by the FDA for the treatment of partial epileptic seizures and neuropathic pain (post-herpetic neuralgia). Only pregabalin is recommended for the management of fibromyalgia, diabetic neuropathy, and as a second-line therapy for the treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) [9]. In addition, up to 95% of gabapentinoids are prescribed for off-label indications including the treatment of migraine, mania, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, nonneuropathic pain especially low back pain, mood instability, insomnia, withdrawal symptoms from recreational drugs, and treatment of benzodiazepine addiction [3,10,11]. Both gabapentinoids are well tolerated; their side effects mainly concern the CNS. Dizziness, headache, nausea, confusion, and somnolence are the most common side effects recorded in both drugs, where dizziness and somnolence are more seen with pregabalin [12]. Postmarketing surveillance showed increased number of reports of heart failure and peripheral edema in patients taking pregabalin [13]. Recently, an alarming rate for the intentional misuse of gabapentinoids and their recreational abuse has increased [14].

Related to what has been presented previously, no study has been conducted on knowledge of tramadol and gabapentinoids worldwide; with respect to the practice and attitude of pharmacists concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids dispensing and misuse, several studies have been performed, but none of them took place in Lebanon. The studies were conducted in Jordan, Yemen, and Iran, reflecting the community pharmacists’ experience on dispensing tramadol and gabapentinoids [15–19], by assessing the dispensing patterns, number of prescriptions encountered, and the patient profile. Furthermore, those studies addressed the misuse and abuse patterns of tramadol and gabapentinoids, reflecting an increased potential of abuse of such drugs especially among young individuals. Therefore, we designed the first and only study to evaluate the awareness of Lebanese pharmacists regarding tramadol and gabapentinoids and to determine its predictors; the study also focused on their practice regarding the dispensing of such drugs, especially with their high risk of misuse and abuse.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design and Study Population

To evaluate the awareness of Lebanese pharmacists concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids, a cross-sectional study was conducted in Lebanon over a period of 4 months (from May 1, 2019 to August 31, 2019).

Lebanese pharmacists working in a community pharmacy setting were included in the study. A questionnaire sent online included a description of the study nature and objective. Pharmacists were informed that all the information provided would be kept anonymous and would be used only for research purposes.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

A study done in Amman, Jordan, showed that 24.7% of Jordanian pharmacists considered that the pattern of abuse/misuse of pregabalin was stable with time [17]. Based on this information, the minimum sample size for this study was calculated using Epi Info software version 7.2.2.2 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA). With a precision of 5%, and a confidence level of 95%, a minimum of 286 participants was required.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire written in English. The questionnaire, which was filled in by participants online, was posted and sent to different social media platforms and available in online networks that exclusively include pharmacists. Since there were no previous studies or validated questionnaires concerning pharmacists’ knowledge about tramadol and gabapentinoids, we developed a well-structured questionnaire based on extensive research about tramadol and gabapentinoids pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, side effects, uses, and drug–drug interactions. However, with respect to the practice section, some questions where based on previous studies conducted in different countries concerning the practice and attitude of pharmacists with respect to tramadol and gabapentinoids [15–19].

For validity and reliability, a pretesting of the questionnaire was conducted using a pilot study 2 weeks prior to the actual period of data collection and involved 15 participants. Accordingly, four questions were removed from the questionnaire in order to avoid repetition. The final form of the questionnaire consisted therefore of three sections.

2.4. Questionnaire

The first part consisted of entries covering limited sociodemographic characteristics, in order to protect pharmacists’ anonymity. Demographic details included age, highest degree received, region of practice, and sex. The second part assessed the knowledge of Lebanese pharmacists concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids. Pharmacists were asked about the different uses and side effects of the drugs. Specific questions concerning the difference between addiction, tolerance, and physical and psychological dependence, in addition to the differentiation between drug withdrawal syndrome and overdose signs were asked. Respondents were questioned about the effects sought by tramadol and gabapentinoids addicts, as well as the risk factors leading to addiction. The third part addressed the practice of pharmacists concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids dispensing. Pharmacists were asked to define the sex and age of patients with tramadol and gabapentinoids prescription, in addition to stating whether they dispense such drugs without a prescription, the most frequent brands dispensed, and the number of prescriptions they encounter weekly.

Participants were asked to specify if they ask patients with tramadol or gabapentinoids prescription about their medical history, if they contacted other pharmacies regarding a suspect of abuse, and if they use certain methods to limit addicts’ access to such drugs. In addition, they were asked for their opinion regarding the laws and regulations concerning drugs in Lebanon.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). First descriptive analysis was conducted, and frequency distributions and percentages were collected for responses to all questions. To assess the knowledge of participants regarding tramadol and gabapentinoids, a score for each drug alone, and a total score for both tramadol and gabapentinoids were computed and later dichotomized based on their median into poor knowledge and good knowledge groups. The number and choice of items for each score depended on getting the best value of Cronbach alpha, which increases the reliability of the corresponding score.

A binary logistic regression was performed on the dichotomized knowledge scores to determine their predictors. All independent variables with a p-value <0.2 in bivariate analysis were enrolled in the backward regression. Omnibus tests obtained for all regressions were significantly <0.05 and Hosmer–Lemshow tests were close to 1, ensuring model adequacy. All independent variables with p <0.05 in the regression were considered predictors of knowledge, and the size of their effect was determined using adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) at a 95% Confidence Interval (CI).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

A total of 295 participants were recruited into the study; the majority of respondents (74.9%) were aged between 21 and 35 years. About 52% of the study population consisted of females, and 53.9% had a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy. The region of pharmacy practice was mainly centered in Beirut (34.9%) and Mount Lebanon (26.1%). A summary of the demographic characteristics of participating pharmacists is presented in Table 1.

| Items | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 21–35 | 221 (74.9) |

| 36–55 | 63 (21.4) |

| 56–64 | 11 (3.7) |

| >65 | 0 (0.0) |

| Highest degree achieved | |

| BS Pharmacy | 159 (53.9) |

| Pharm. D. | 57 (19.3) |

| Master’s degree | 73 (24.7) |

| Ph.D. | 6 (2.1) |

| Region of practice | |

| Beirut | 103 (34.9) |

| Bekaa | 17 (5.8) |

| Mount Lebanon | 77 (26.1) |

| Baalbeck | 7 (2.4) |

| South | 57 (19.3) |

| North | 7 (2.4) |

| Nabatieh | 27 (9.1) |

| Akkar | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 139 (47.1) |

| Female | 156 (52.9) |

Demographic details of participating pharmacists

More than half of the pharmacists considered that pregabalin and gabapentin are mainly used and prescribed for neuropathic pain and partial seizures with a percentage of 71.5% and 66.4% for pregabalin, and 68.1% and 69.8% for gabapentin, respectively. Regarding tramadol, 83.1% of pharmacists responded that it is used for moderate-to-severe pain, whereas only 27.5% claimed that it is used for mild-to-moderate pain (see Table 2).

| Items | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Pregabalin | |

| Partial seizures | 196 (66.4) |

| Anxiety | 41 (13.9) |

| Neuropathic pain | 211 (71.5) |

| Fibromyalgia | 113 (38.3) |

| Mood instability | 44 (14.9) |

| Insomnia | 63 (21.4) |

| Low back pain | 181 (61.4) |

| Migraine | 20 (6.8) |

| Bipolar disorder | 20 (6.8) |

| Withdrawal symptoms from recreational drugs | 31 (10.5) |

| Gabapentin | |

| Partial seizures | 206 (69.8) |

| Anxiety | 44 (14.9) |

| Neuropathic pain | 201 (68.1) |

| Fibromyalgia | 93 (31.5) |

| Mood instability | 38 (12.9) |

| Insomnia | 62 (21) |

| Low back pain | 162 (54.9) |

| Migraine | 25 (8.5) |

| Bipolar disorder | 24 (8.1) |

| Withdrawal symptoms from recreational drugs | 34 (11.5) |

| Tramadol | |

| Mild-to-moderate pain | 81 (27.5) |

| Moderate-to-severe pain | 245 (83.1) |

| Management of opioid use disorders | 87 (29.5) |

Pharmacists’ responses concerning uses of pregabalin, gabapentin, and tramadol (n = 295)

Somnolence was the major side effect mentioned by pharmacists for pregabalin (65.4%) and gabapentin (68.1%), whereas edema, heart failure, and suicidal ideation where the least mentioned. Regarding tramadol, pharmacists considered that its major side effects are sedation (70.2%) and hallucinations (66.8%).

Moreover, respondents reported that gabapentinoids interact mostly with alcohol (64.7%) and 42.7% mentioned that it may interact with Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). Regarding tramadol, lithium followed by ritonavir were the most commonly reported drugs to interact with tramadol; others in a descending order included second-generation antipsychotics and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs).

Most of the pharmacists (87.5%) considered that they are able to differentiate between addiction, tolerance, physical dependence, and psychological dependence, where 61.6% of pharmacists considered that addiction is not defined as loss of functional potency. Moving on to drug withdrawal syndrome, 88.5% of pharmacists indicated their knowledge of its signs, considering that drug craving (76.6%) is the most common sign of it. Regarding the signs of tramadol and gabapentinoids overdose, respiratory distress (70.5%) followed by irregular heart rate (67.8%) were the most commonly reported signs of tramadol and gabapentinoids overdose.

Euphoria (55.9%) was considered as the main effect sought by tramadol and gabapentinoids addicts, followed by the need for pain relief (20.4%). The majority of pharmacists considered society (61.4%), pain sensation (57.3%), and genetic factors (52.5%) as the most common risk factors leading to tramadol and gabapentinoid addiction.

Furthermore, among patients with tramadol and gabapentinoids prescriptions, 55.9% of pharmacists reported that they were mainly males, whose age ranged between 18 and 30 years for tramadol consumers, whereas for gabapentinoids consumers the age ranged between 31 and 49 years.

Regarding pharmacists’ response about selling tramadol and gabapentinoids without a prescription, the majority of them refused to dispense such drugs without a legal prescription (97.6% and 71.5%, respectively). However, in the case of gabapentinoids, 20.7% would dispense it occasionally based on the case and the patient, and 7.8% would dispense it without a prescription. With respect to pregabalin, gabapentin, and tramadol, the most common brands prescribed based on pharmacists’ experience were Lyrica (Pfizer, Belgium) (42.4%), Gabamox (West Pharma, Portugal) (30.5%), and Tramal (Grünenthal Pharma AG, Germany) (57.6%), respectively.

Most of the pharmacists reported encountering one to three prescriptions of tramadol (63.7%) and gabapentinoids (50.8%) per week. From those receiving such prescriptions, only 54.6% of pharmacists would ask the patient about their history and any possible current drug administration, whereas 45.4% would not.

Only 18.6% of participating Lebanese pharmacists reported that they contacted other pharmacies in the area regarding a client suspected of tramadol and gabapentinoids abuse, whereas 66.8% did not contact any pharmacy in the area concerning this issue. Furthermore, 14.6% claimed that they do not remember contacting other pharmacies.

Pharmacists used several methods to limit customers’ access to products of abuse, the most common of which was refusing to sell the drug (45.8%). Other methods include hiding such drugs from patient sight and claiming that the drug is not available in the pharmacy (33.2%) and providing advice to patients (21.0%).

More than half of the pharmacists (51.3%) considered that doctors play a major role in tramadol and gabapentinoids misuse, whereas 10.5% of the participants reported that pharmacists also play a role in misuse of such drugs. Only five pharmacists reported other parties that may play a role in misuse—the patient (1%), drug companies (0.3%), and the government (0.3%)—owing to the absence of pertinent laws.

In Lebanon 43.7% of pharmacists believe that current governmental regulations and laws are not adequate to control the problem of tramadol and gabapentinoids misuse, whereas only 37.3% reported that current regulations are able to control the misuse problem. About 86.8% of participants reported that the implementation of new laws and the improvement of governmental supervision on tramadol and gabapentinoids will limit their misuse, whereas only 4.4% claimed that such steps would not help in controlling the misuse problem.

3.2. Knowledge Score

To assess the level of knowledge of tramadol and gabapentinoids among participants, the survey questions were grouped into individual scores. Three scores were obtained, including a global knowledge score representing the knowledge of both tramadol and gabapentinoids consisting of 41 items. In addition, two other scores representing the knowledge of tramadol and gabapentinoids individually were created, which included 40 and 35 items, respectively.

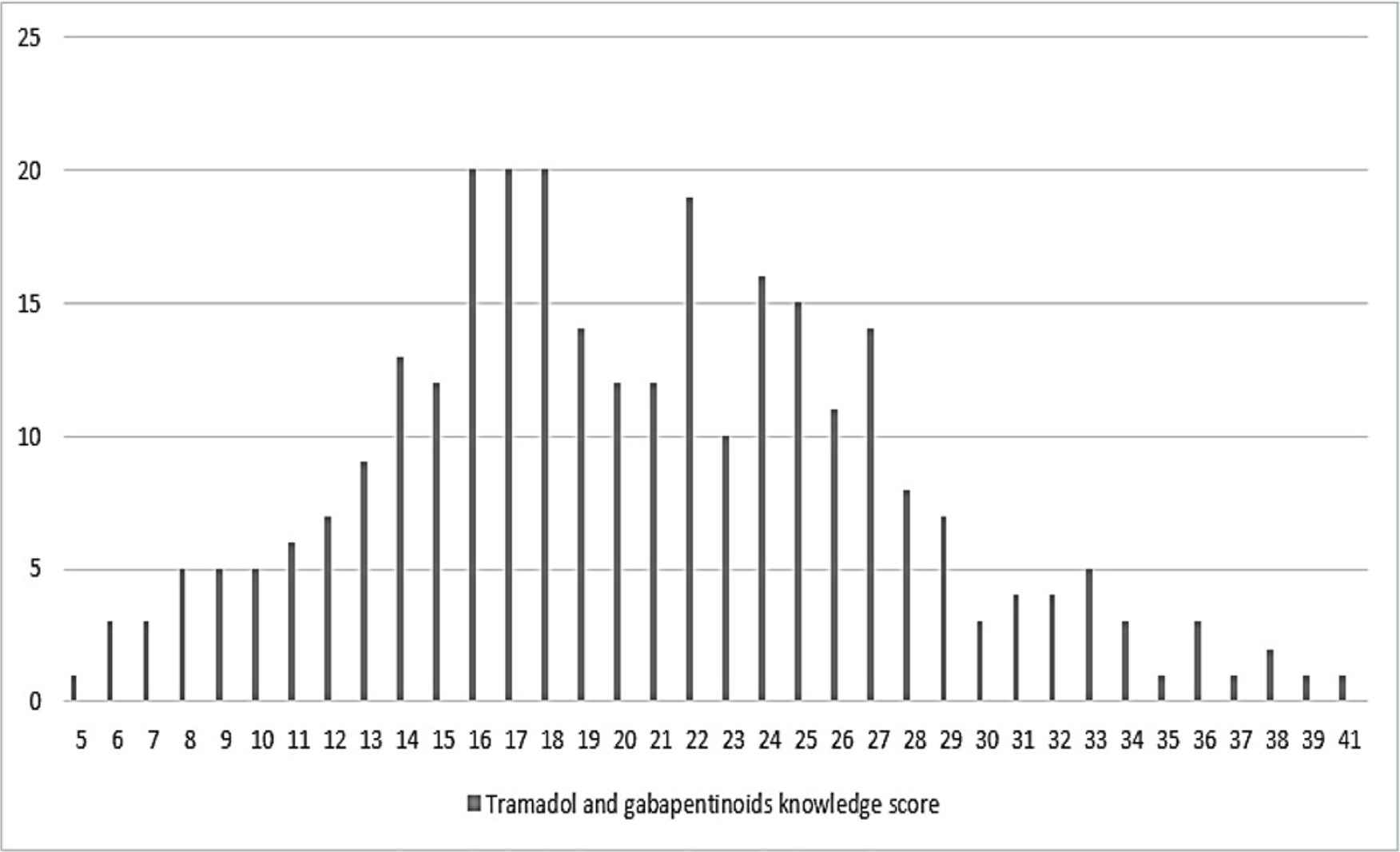

Regarding the global score representing the knowledge of both tramadol and gabapentinoids, a minimum score of 5 and a maximum score of 41 were obtained; a mean score of 20 ± 7 and a median equal to 20 were obtained, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, where the latter shows the distribution of global knowledge score. About half of the pharmacists had good knowledge concerning both tramadol and gabapentinoids (51.5%), whereas 48.5% had poor knowledge.

| Score | Mean ± SD | Median | Poor knowledge, n (%) | Good knowledge, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total knowledge score | 20 ± 7 | 20 | 143 (48.5) | 152 (51.5) |

| Tramadol knowledge score | 18 ± 7 | 18 | 139 (47.1) | 156 (52.9) |

| Gabapentinoids knowledge score | 18 ± 6 | 18 | 140 (47.5) | 155 (52.5) |

SD, standard deviation.

Descriptive analysis of each computed score (n = 295)

Distribution of pharmacists total knowledge score of tramadol and gabapentinoids.

Concerning tramadol knowledge score, a minimum score of 5 and a maximum score of 39 were obtained, with a mean of 18 ± 7 and a median of 18. Pharmacists with good knowledge represented 52.9% of participants, whereas 47.1% of pharmacists had poor knowledge concerning tramadol.

With respect to knowledge about gabapentinoids, 52.5% of participants had good knowledge whereas 47.5% had poor knowledge. A minimum score of 5 and a maximum score of 34 were obtained, with a mean of 18 ± 6 and a median equal to 18 (Table 3).

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

Pharmacists’ knowledge about tramadol and gabapentinoids, separately, was associated with highest educational degree achieved, where having a master’s degree increases knowledge by about two times compared with having a bachelor’s degree only (OR = 2.073, p = 0.018; OR = 2.033, p = 0.018, respectively) (Table 4).

| Dependent | Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Dichotomized global knowledge scorea | Region of practice (Nabatieh) | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.799 | 0.0015* |

| Master’s degree | 2.354 | 1.287 | 4.306 | 0.005* | |

| Dichotomized tramadol knowledge scoreb | Master’s degree | 2.073 | 1.136 | 3.782 | 0.018* |

| Dichotomized gabapentinoids knowledge scorec | Master’s degree | 2.033 | 1.132 | 3.652 | 0.018* |

| Age 56–64 years | 0.21 | 0.044 | 1.005 | 0.051 | |

p <0.05, level of significance.

Global knowledge score: Omnibus test, p <0.05; Hosmer–Lemshow test, p = 0.93, that is, >0.10; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.107; overall predicted percentage = 61.7%. Independent variables: region of practice, highest degree received.

Tramadol knowledge score: Omnibus test, p = 0.022, that is, <0.05; Hosmer–Lemshow test, p = 0.505, that is, >0.10; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.085; overall predicted percentage = 58.3%. Independent variable: highest degree received.

Gabapentinoids knowledge score: Omnibus test, p = 0.006, that is, <0.05; Hosmer–Lemshow test, p = 0.229, that is, >0.10; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.072; overall predicted percentage = 59.7%. Independent variables: highest degree received, age.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Binary logistic regression using knowledge scores as the dependent variable

Only Nabatieh province and having a master’s degree were associated with pharmacists’ global knowledge. Nabatieh participants have lower knowledge compared with those living in Beirut by 69% (OR = 0.31, p = 0.015), whereas having a master’s degree increases knowledge by about two times than having a bachelor’s degree only (OR = 2.354, p = 0.005) (Table 4). It should be noted, however, that the survey was administered online, and there is no sufficient sample size representing each region, so those results relating to Nabatieh province may not be reliable or representative of the population.

4. DISCUSSION

This study highlighted Lebanese community pharmacists’ knowledge concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids, in addition to their practices concerning the dispensation of such drugs. This is the first study conducted to explore such aspects concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids.

Pharmacists were aware of tramadol use and indication as an analgesic for moderate to severe pain. Regarding the side effects of tramadol, pharmacists had general and superficial knowledge concerning such effects, where most of them focused on sedation, hallucinations, and euphoria, and neglected the major side effects such as seizures and serotonin syndrome. This can be explained by the focus of pharmacists on tramadol as a substance of addiction.

With respect to drug–drug interactions, pharmacists recognized the probability of tramadol to interact with listed drugs, especially the fact that the combination of tramadol with such drugs would increase the risk of serotonin syndrome, in particular, its combination with SSRIs.

As for pregabalin and gabapentin, pharmacists are knowledgeable about their main uses for treating partial seizures and neuropathic pain. Concerning fibromyalgia and anxiety, some of the pharmacists noted that both pregabalin and gabapentin can be used for treating such conditions, which is not accurate—in fact, only pregabalin is used for fibromyalgia and as a second-line therapy for general anxiety disorders.

Regarding the side effects, results showed that pharmacists think that the two drugs have the same adverse effects. Gabapentin had higher percentages than pregabalin concerning somnolence, dizziness, and euphoria although such effects are experienced more often with pregabalin. In addition to that, pharmacists considered heart failure as a side effect for both drugs despite that it is exclusively for pregabalin; reflecting that pharmacists consider that both pregabalin and gabapentin can be used for the same indications and has the same side effects.

Drug–drug interactions are detected by pharmacists; however, most of the pharmacists considered that gabapentinoids may interact with NSAIDs, which is incorrect. Pharmacists are able to differentiate between addiction, tolerance, physical dependence, and psychological dependence. In addition, pharmacists have proper knowledge concerning withdrawal syndrome and drug overdose signs. Euphoria was chosen by pharmacists to be the main effect sought by tramadol and gabapentinoids addicts, because of the general concept that addicts of any type mainly seek euphoria. Regarding risk factors leading to tramadol and gabapentinoid addiction, participants focused on the role of the society in addiction, in addition to pain and genetic factors. Pharmacists considered that addiction in general had been on the rise in Lebanon especially among young people because of social problems, increased poverty, economic deprivation, and political corruption, which collectively may lead young individuals to addiction and abuse. Statistical data in Lebanon indicate an increase in the rate of use of addictive substances, drugs, and alcohol, especially among youthful individuals [20]. It should be noted that according to a large population-based study on all first-time pregabalin, gabapentin, and duloxetine users in France, misuse was more frequent among pregabalin users (12.8% were dispensed a higher daily dose than recommended), compared to gabapentin (6.6%) and duloxetine users (9.7%) [21].

According to pharmacists, patients with tramadol or gabapentinoid prescriptions where mainly young males. This can be explained by the stigma associated with the use of such drugs especially tramadol, accounting for the low number of females with such prescriptions. This outcome is similar to two studies conducted in Denmark and Jordan, where male sex and prescriptions of tramadol and gabapentin are associated [14,17]. Regarding age groups of consumers, pharmacists described them as young individuals aged 18–30 years for tramadol and aged 31–49 years for gabapentinoids. Similarly, in Iran tramadol users and abusers are usually of a young age [19].

On average, Lebanese pharmacists encounter about one to three prescriptions of tramadol and gabapentinoids, which varies depending on the pharmacy location and population. Regarding dispensing tramadol and gabapetinoids, 97.6% and 71.5% of pharmacists confirmed that they do not dispense these drugs without a prescription, respectively. However, some pharmacists confirmed that they might dispense gabapentinoids without a prescription especially as there are no clear regulations regarding dispensation of gabapentinoids. Inspectors from the Ministry of Public Health usually ask about tramadol medication records but never about gabapentinoids. In June 1, 2015, a memo restricting the sale of any tramadol- and pregabalin-containing agent was issued, and in February 2016 the Health Minister reaffirmed that rule [22].

Only 54.6% of pharmacists would ask patients with tramadol or gabapentinoids prescription about their medical history and any drug taken in order to avoid any drug–drug interaction, and make sure that treatment given would not cause any harm.

Networking among pharmacists may help to limit the problem of abuse and misuse of drugs. Nevertheless, the majority (66.8%) of Lebanese pharmacists would not contact other pharmacies in the area concerning any patient suspected of drug abuse. There is no proper communication among different community pharmacies in each area, in addition to the competition that exists between them. However, such encounters with addicts could be minimized if pharmacists networked more frequently with one another so that a suspected abuser would be reported to other pharmacies in the area.

The methods used by Lebanese pharmacists to limit tramadol and gabapentinoids abusers from access to drugs do not differ from those reported by pharmacists in other countries such as Yemen and Jordan [17,16]. Methods used by pharmacists include mainly refusal of selling such products, keeping them out of sight, and providing advice to patients.

Pharmacists considered doctors to be the most responsible for tramadol and gabapentinoid abuse, as they might write a prescription for these drugs under the patient’s request and get paid for it. Moreover, some doctors randomly prescribe such drugs without always being aware of all the dangerous consequences or might even provide these drugs to patients as well.

According to Lebanese pharmacists, current government regulations and laws are not adequate to control the problem of tramadol and gabapentinoid misuse because of lack of monitoring. There is no efficient implementation of the rules—when available—concerning the dispensation of such drugs without a prescription. In certain areas, patients can buy tramadol and gabapentinoids easily from pharmacies with the lack of surveillance on doctors’ random prescriptions concerning such drugs. However, many pharmacists believe that with improved governmental supervision and implementation of new laws, there is a chance to limit gabapentinoid and tramadol abuse.

Based on this study, having a master’s degree improves pharmacists’ knowledge by about two times compared to just having a bachelor’s degree. Therefore, educational programs for pharmacists must be designed to help improve their knowledge concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids especially considering the fact that Lebanese pharmacists encounter prescriptions of such drugs on a daily basis and because of the high level of tramadol and gabapentinoid misuse.

This study was based on pharmacists’ perceptions, which were highly subjective, and represented only a single point of view. From the obtained results, the respondents were mainly from Beirut and Mount Lebanon area, with the absence of participants from some regions. The survey was administered online, which makes it difficult to reach certain types of participants such as those who do not have Internet access or have no social media accounts.

Nevertheless, the strength of our study resides in the fact that it is the first study conducted in the world regarding knowledge of tramadol and gabapentinoids among pharmacists. It is also the first study conducted in Lebanon concerning the practice of Lebanese pharmacists in relation to such drugs. In addition, we were able to obtain the required sample size, which enhances the credibility of our study.

5. CONCLUSION

Lebanese pharmacists encounter patients with tramadol and gabapentinoids prescriptions on a daily basis, which makes it necessary for them to have appropriate knowledge and proper practice and attitude when dispensing such drugs. This study reflected that pharmacists’ knowledge concerning both tramadol and gabapentinoids on different aspects needs to be improved. Therefore, pharmacists should be enrolled in continuous education programs in order to improve their knowledge concerning tramadol and gabapentinoids at the level of pharmacology, drug–drug interactions, risk of abuse, and addiction to such drugs. In addition, new laws concerning these two drugs exclusively must be issued in order to prevent problems relating to illegal dispensation of such drugs. Pharmacists should be ethical when dispensing prescription drugs especially if they suspect that the patient is an addict. Furthermore, the Ministry of Public Health should take steps to keep track of random prescription of tramadol and gabapentinoids by doctors and dispensing by pharmacists. In addition, patient education by pharmacists should be enhanced in order to increase awareness toward the proper use of such drugs, leading to the reduction of abuse and misuse problems.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

FT and RT contributed in study conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis and writing (original draft). LHJ, JK, and GE-C contributed in formal analysis and writing (editing) the manuscript. SA contributed in study conceptualization. NL contributed in formal analysis, supervision of the statistical part. DK contributed in study conceptualization, project administration, supervised the project, writing (review and editing) the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- α2γ,

alpha-2-gamma;

- CNS,

central nervous system;

- FDA,

Food and Drug Administration;

- GABA,

gamma-aminobutyric acid;

- GAD,

generalized anxiety disorder;

- NSAIDs,

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

- SSRI,

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors;

- SD,

standard deviation;

- SPSS,

Statistical Program for Social Sciences;

- VGCC,

voltage-dependent calcium channels.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Farah Tarhini AU - Reem Taky AU - Lynne H. Jaffal AU - Jinan Kresht AU - Gaelle El-Chaer AU - Sanaa Awada AU - Nathalie Lahoud AU - Dalia Khachman PY - 2020 DA - 2020/02/13 TI - Awareness of Lebanese Pharmacists towards the Use and Misuse of Gabapentinoids and Tramadol: A Cross-sectional Survey JO - Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Journal SP - 24 EP - 30 VL - 2 IS - 1 SN - 2590-3349 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/dsahmj.k.200206.002 DO - 10.2991/dsahmj.k.200206.002 ID - Tarhini2020 ER -