Adherence to medications and associated factors: A cross-sectional study among Palestinian hypertensive patients

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.05.005How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Adherence; Hypertension; Forgetfulness; Palestine

- Abstract

Objective: To assess adherence of Palestinian hypertensive patients to therapy and to investigate the effect of a range of demographic and psychosocial variables on medication adherence.

Methods: A questionnaire-based, cross-sectional descriptive study was undertaken at a group of outpatient clinics of the Ministry of Health, in addition to a group of private clinics and pharmacies in the West Bank. Social and demographic variables and self-reported drug adherence (Morisky scale) were determined for each patient.

Results: Low adherence with medications was present in 244 (54.2%) of the patients. The multivariate logistic regression showed that younger age (<45 years), living in a village compared with a city, evaluating health status as very good, good or poor compared with excellent, forgetfulness, fear of getting used to medication, adverse effect, and dissatisfaction with treatment had a statistically significant association with lower levels of medication adherence (P < 0.05).

Conclusions: Poor adherence to medications was very common. The findings of this study may be used to identify the subset of population at risk of poor adherence who should be targeted for interventions to achieve better blood pressure control and hence prevent complications. This study should encourage the health policy makers in Palestine to implement strategies to reduce non-compliance, and thus contribute toward reducing national health care expenditures. Better patient education and communication with healthcare professionals could improve some factors that decrease adherence such as forgetfulness and dissatisfaction with treatment.

- Copyright

- © 2014 Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior-taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health-care provider” [1]. Generally, adherence to a medical regimen is most likely to be a problem in chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, osteoporosis, and asthma, and is responsible for suboptimal clinical outcomes, decreased quality of life, and increased expense to the health-care system [1–3]. Poor adherence to treatment of chronic diseases is a worldwide problem of striking magnitude. According to the World Health Organization adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses in developed countries averages 50%. In developing countries, the rates are even lower [1].

Hypertension is a significant public health problem in many countries. It remains an important public health challenge and one of the most important risk factors for coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure and end stage renal disease [4,5]. Lowering blood pressure by antihypertensive drugs reduces the risks of cardiovascular events, stroke, and total mortality [6,7]. Lack of compliance with blood pressure-lowering medication is a major reason for poor control of hypertension. Patients with high blood pressure may fail to take their medication because of the chronic nature of the disease and the absence of overt symptoms [8]. In Palestine, hypertension is among the leading causes of death; it is the eighth cause of death and is a risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases which represent the first and second causes of death [9].

Factors that affect medication adherence are complex; low adherence was reported among younger individuals, men, and black persons. Other factors that were reported to negatively impact adherence to prescribed therapies include beliefs about illness and treatment, forgetfulness, side effects of medications, complexity of treatment regimens, lack of knowledge regarding hypertension and its treatment, financial difficulties, psychological factors, social support, quality of the relationship between patient and physician and poor quality of life [5,10–16].

Studies related to medication adherence are very limited in Palestine. Compared with other variables being considered in therapeutics, adherence to medications has long been given minor attention although it affects every aspect of medical care. This study appears to be the first to investigate the rate of medication adherence and its associated factors in hypertensive patients from the West Bank. The objectives of this study are to measure the rate of medication adherence, to investigate the factors associated with this adherence and the reasons for poor adherence. This study could be helpful to health policy makers in Palestine to implement health education strategies to reduce poor adherence and thus to reduce complications of the disease and national health costs.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient selection

The study was a questionnaire-based cross-sectional descriptive study. It was conducted between September and December 2011. It included a simple random sample from patients visiting outpatient clinics of governmental primary healthcare centers in addition to a group of private clinics and pharmacies in the West Bank. Approval to perform the study was obtained from the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) committee at An-Najah National University. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and did not endanger the well-being of the patients. Patients who met the following criteria were invited to participate in this study: (1) Patients ⩾ 18 years; (2) Those who had been diagnosed with hypertension; and (3) Those who were on prescribed antihypertensive medications for at least one month. Patients who agreed to participate were explained the nature and the objectives of the study, and informed consent was formally obtained.

Since there was no available literature showing the prevalence of adherence among the Palestinian community in general, a 50% expected prevalence was used; minimum sample size was calculated to be 384, so 500 patients were asked to participate in the study.

2.2. Data collection

The data collection tool was a questionnaire, designed-based on an extensive literature review of similar studies [2,5,17]. The questionnaire included information regarding patient demographics and clinical characteristics such as: sex, age, education, insurance, income, medical history, and co-morbidities. Patients were asked about their prescribed medication regimen, including the number of their antihypertensive drugs and other medications – if present – frequency per day, side effects of medications and reasons for not taking their medications. Adherence was assessed through the 8-item self-report Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) [5]. Each item measures a specific medication-taking behavior. Approval was obtained from professor Morisky to use his scale. This scale is a questionnaire with a high reliability and validity, which has been particularly useful in chronic conditions such as hypertension [5,12]. Highly adherent patients were identified with the score of 8 on the scale, medium adherers with a score of 6 to <8, and low adherers with a score of <6. For studying factors affecting adherence, patients were divided into two groups: poor adherent (score < 6) versus adherent (score 6–8), because in the Morisky et al. study, correct classification with blood pressure control was based on a dichotomous low versus high/medium level of adherence, which had a rate of 80.3%. When they used a cut-off point of <6, the sensitivity of the measure to identify patients with poor blood pressure control was estimated to be 93% [5].

Forward translation of the original scale was undertaken by translation from English to the Arabic language to produce a version that was semantically and conceptually as close as possible to the original questionnaire. Then reverse translation of this version from Arabic to English was carried out by another translator. After discussion between the translators and the researchers, inconsistencies were resolved and a final version, ready for testing, was generated. The translated questionnaire was distributed to 20 patients who completed the questionnaire and commented on the questions. These individuals were not included in the study.

2.3. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Means ± standard deviation was computed for continuous data. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. In univariate analyses, categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the odds ratios of factors that showed a statistically significant association with medication adherence in the univariate analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ characteristics

From 500 people approached, 450 (90.0%) agreed to participate in the study. Females accounted for 253 (56.2%) of the total sample. The average age was 59.1 (±12.2) years (from 27 to 90 years). Around one half of the participants (241, 53.6%) had another chronic disease and more than two-thirds of them (317 70.4%) had a governmental health insurance plan. The mean number of antihypertensive medications was 2.35 (±1.49). Based on the MMAS, only 76 (16.9%) participants had high adherence, 130 (28.9%) had medium adherence and 244 (54.2%) had poor adherence. Table 1 shows the responses to the Morisky scale questions.

| Number | Question | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | ||

| 1 | Do you sometimes forget to take your high blood pressure pills? | 262 (58.2) | 188 (41.8) |

| 2 | Over the past 2 weeks, were there any days when you did not take your high blood pressure medicine? | 162 (36.0) | 288 (64.0) |

| 3 | Have you ever cut back or stopped taking your medication without telling your doctor because you felt worse when you took it? | 124 (27.6) | 326 (72.4) |

| 4 | When you travel or leave home, do you sometimes forget to bring along your medications? | 181 (40.2) | 269 (59.8) |

| 5 | Did you take your high blood pressure medicine yesterday? | 378 (84.0) | 72 (16.0) |

| 6 | When you feel like your blood pressure is under control, do you sometimes stop taking your medicine? | 128 (28.4) | 322 (71.6) |

| 7 | Do you ever feel hassled about sticking to your blood pressure treatment plan? | 216 (48.0) | 234 (52.0) |

| 8 | How often do you have difficulty remembering to take all your blood pressure medication? | ||

| Never 172 (38.2%) | |||

| Once in a while 148 (32.9%) | |||

| Sometimes 81 (18.0%) | |||

| Usually 28 (6.2%) | |||

| All the time 21(4.7%) |

Responses to Morisky scale questions.

In univariate analysis, factors that were associated with poor medication adherence were younger age, living in a village or a camp, having lower income, receiving a higher number of antihypertensive tablets daily or a higher dosing frequency, evaluating health status as very good, good or poor, and having no other chronic disease, (p < 0.05). The main socio-demographic and clinical baseline characteristics of the responders and their association with poor adherence are shown in Table 2.

| Characteristic | Total sample | MMAS category (score range) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 450 | Low (<6) | Medium/High (6–8) | ||

| N = 244 | N = 206 | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Age | 0.006 | |||

| 18–44 | 41 | 32 (78.0) | 9 (22.0) | |

| 45–64 | 259 | 134 (51.7) | 125 (48.3) | |

| ⩾65 | 150 | 78 (52.0) | 72 (48.0) | |

| Gender | 0.972 | |||

| Male | 197 | 107 (54.3) | 90(45.7) | |

| Female | 253 | 137 (54.2) | 116 (45.8) | |

| Education | 0.590 | |||

| College/ university or higher | 129 | 66 (51.2) | 63 (48.8) | |

| High school | 118 | 68 (57.6) | 50 (42.4) | |

| Primary/middle school | 112 | 64 (57.1) | 48 (42.9) | |

| Illiterate | 91 | 46 (50.5) | 45(49.5) | |

| Area of residence | 0.001 | |||

| City | 233 | 106 (45.5) | 127 (54.5) | |

| Village | 175 | 111 (63.4) | 64 (36.6) | |

| Camp | 42 | 27 (64.3) | 15 (35.7) | |

| Household monthly income | 0.035 | |||

| <400 JD | 247 | 145 (58.7) | 102 (41.3) | |

| ⩾400 JD | 203 | 99 (48.8) | 104 (51.2) | |

| Marital status | 0.088 | |||

| Single | 26 | 16 (61.5) | 10 (38.5) | |

| Married | 341 | 178 (52.2) | 163 (47.8) | |

| Divorced | 17 | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Widowed | 66 | 36 (54.5) | 30 (45.5) | |

| Health insurance | 0.505 | |||

| Governmental | 317 | 169 (53.3) | 148 (46.7) | |

| Private | 42 | 21 (50.0) | 21 (50.0) | |

| No insurance | 91 | 54 (59.3) | 37 (40.7) | |

| Current health status | 0.012 | |||

| Excellent | 24 | 7 (29.2) | 17 (70.8) | |

| Very good | 123 | 75 (61.0) | 48 (39.0) | |

| Good | 178 | 102 (57.3) | 76 (42.7) | |

| Poor | 125 | 60 (48.0) | 65 (52.0) | |

| Another chronic disease | 0.009 | |||

| Yes | 241 | 117 (48.5) | 124 (51.5) | |

| No | 209 | 127 (60.8) | 82 (39.2) | |

| Number of tablets per day | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 140 | 59 (42.1) | 81 (57.9) | |

| 2 | 150 | 85 (56.7) | 65 (43.3) | |

| ⩾3 | 160 | 100 (62.5) | 60 (37.5) | |

| Number of medications per day | 0.496 | |||

| 1 | 221 | 114 (51.6) | 107 (48.4) | |

| 2 | 163 | 94 (57.7) | 69 (42.3) | |

| ⩾3 | 66 | 36 (54.5) | 30 (45.5) | |

| Frequency of dosing | <0.0001 | |||

| 1 | 192 | 80 (41.7) | 112 (58.3) | |

| >1 | 258 | 164 (63.6) | 94 (36.4) | |

Univariate analysis of the association of potential demographic and clinical variables with self-reported adherence.

Patients’ reasons for low-adherence to medications were recorded as forgetfulness 275 (61.1%), cost 72 (16.0%), lack of access to medication 66 (14.7%), traveling 53 (11.8%), dissatisfaction with treatment 45 (10.0%), adverse effect 45 (10.0%), fear of getting used to medication 33 (7.3%), and other reasons such as the unavailability of these medications at the Ministry of Health healthcare centers 40 (8.9%). Among these reasons, forgetfulness, fear of getting used to medication, adverse effect, and dissatisfaction with treatment had a statistically significant association with poor adherence (Table 3).

| Factor | Total no. | MMAS category (score range) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<6) | Medium/High (6–8) | |||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |||

| Forgetfulness | 275 | 179 (65.1) | 96 (34.9) | <0.0001 |

| Cost of medication | 72 | 40 (55.6) | 32(44.4) | 0.804 |

| Lack of access to medication | 66 | 41 (62.1) | 25 (37.9) | 0.163 |

| Traveling | 53 | 34 (64.2) | 19 (35.8) | 0.122 |

| Dissatisfaction with treatment | 45 | 36 (80.0) | 9 (20.0) | <0.0001 |

| Side effects | 45 | 35 (77.8) | 10(22.2) | 0.001 |

| Others | 40 | 19 (47.5) | 21 (52.5) | 0.371 |

| Fear of getting used to medication | 33 | 29 (87.9) | 4 (12.1) | <0.0001 |

Patients’ reasons for non-adherence to medications.

The multivariate logistic regression showed that younger age (<45 years), living in a village compared to a city, evaluating health status as very good, good or poor compared with excellent, forgetfulness, fear of getting used to medication, adverse effect, and dissatisfaction with treatment had a statistically significant association with lower levels of medication adherence (P < 0.05) as shown in Table 4.

| Odd ratio (OR) | 95% confidence interval (CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–44 | 1 | |

| 45–64 | 0.40 | 0.157–0.99 |

| ⩾65 | 0.32 | 0.12–0.87 |

| Area of residence | ||

| City | 1 | |

| Village | 1.79 | 1.10–2.92 |

| Current health status | ||

| Excellent | 1 | |

| Very good | 5.58 | 1.83–17.04 |

| Good | 5.40 | 1.78–16.32 |

| Poor | 4.55 | 1.44–14.41 |

| Forgetfulness | 5.12 | 3.12–8.41 |

| Dissatisfaction with treatment | 2.93 | 1.22–7.02 |

| Side effects | 4.58 | 1.87–11.25 |

| Fear of getting used to medication | 8.00 | 2.44–26.19 |

Odds ratios of determinants of poor medication adherence.

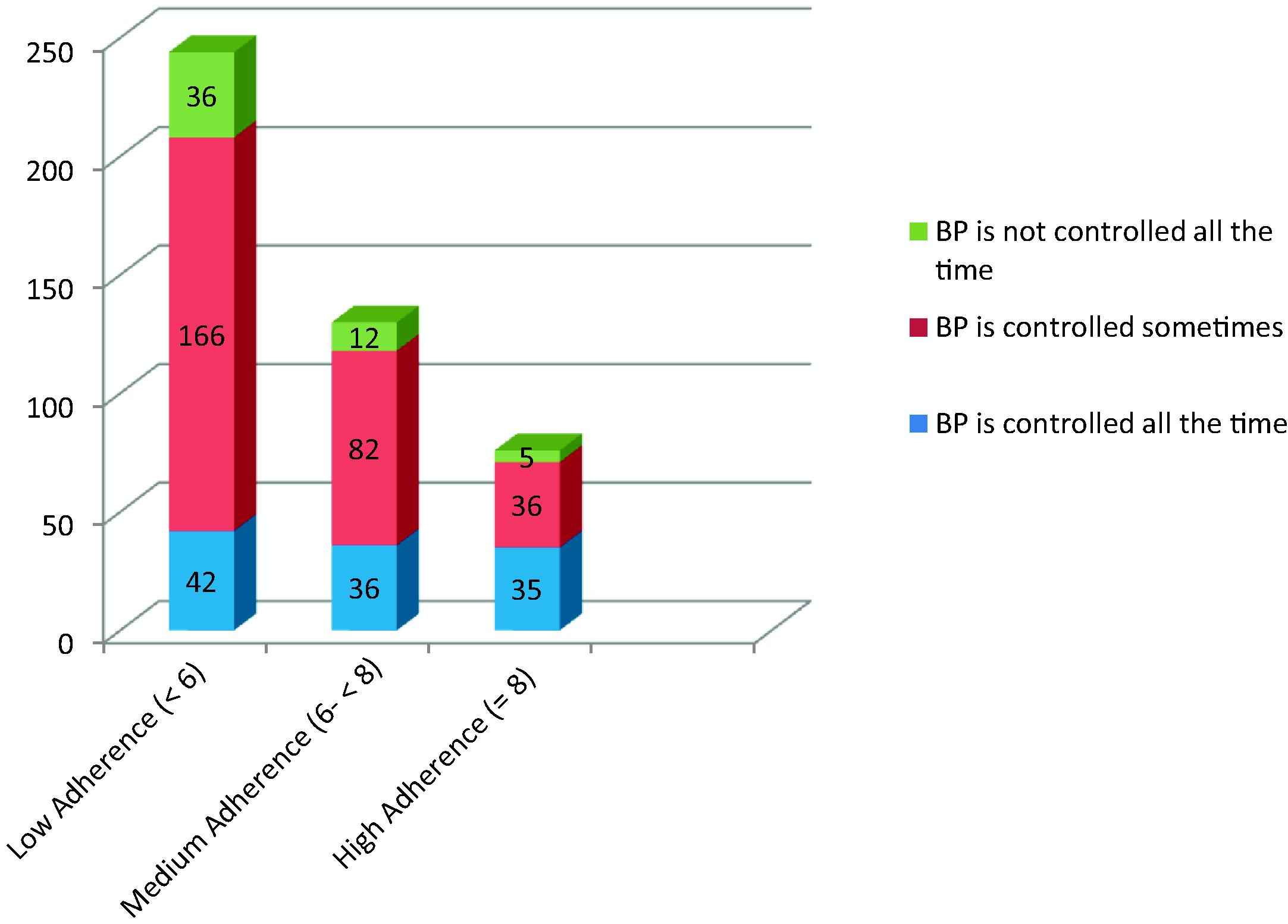

The Chi-square test showed a significant relationship between MMAS categories and reported control of blood pressure. Among the patients, 113 (25.1%) reported that their blood pressure measurements were within the goal all the time, 284 (63.1) said they were within the goal sometimes, and 53 (11.8%) reported that their measurements were above the goal all the time (Fig. 1).

Relationship between adherence scale and blood pressure control.

4. Discussion

Medication adherence is a key component of treatment for patients with hypertension. This study found a very high percentage of low adherence (54.2% of patients). This means that for many hypertensive patients, medication adherence needs to be improved. This result is close to what has been reported from Taiwan (47.5%) [18], Saudi Arabia (47.0%) [19], and Pakistan (64.7%) [11]. It is higher than studies from the United States (9.0%) [12], Egypt (25.9%) [20] and Ethiopia (35.4%) [21]. However, the lack of standard measurements prevents comparisons being made between studies and across populations.

In this study, younger age (<45 years), living in a village compared with a city, evaluating health status as very good, good or poor compared with excellent, forgetfulness, fear of getting used to medication, adverse effect, and dissatisfaction with treatment had a statistically significant association with lower levels of medication adherence (P < 0.05) in multivariate logistic regression. Effect of age is consistent with some other studies; for example, in a study from the United Kingdom, patients over the age of 50 were found to be more adherent than those in the younger age groups [22], and in Pakistan, subjects who were less than 40 years old were less adherent than those older than 70. The highest mean adherence rate was observed in the age group 70–80 years [17]. It seems that the people care more when they get older and/or start to have disease complications. This should be considered during patient counseling; complications of hypertension in addition to risks of poor adherence to medications should be explained well to patients in the younger age groups. Living in a village compared with a city was a reason for poor adherence also; this may be related to lower levels of education or income in addition to difficulties in reaching doctors and health-care facilities. Evaluating health status as very good, good or poor compared with excellent was significantly associated with poor adherence. In some studies, lower medication adherence was associated with poor health-related quality of life [11]. Poor health may cause the patient to be depressed and less satisfied with his medications. Forgetting to take medication was the main reason for low-adherence in this study similar to other studies [13,17]; efforts of greater emphasis on this point are recommended. Adverse effects are well-known reasons for poor adherence to medications [19,20]. The patients who were fearful of getting used to medication and who were dissatisfied with treatment were significantly associated with poor adherence. Better communication with prescribers and pharmacists might solve these problems. It can be noticed that a low level of adherence was not influenced by sex or by the level of education. This might reflect an important cultural behavior that could influence the proposed strategies to improve adherence. They should cover both males and females from different educational levels.

Better communication with health-care providers and better education about the medications and the nature of the disease can be of a great value in improving patients’ adherence to their medications. Identifying patients at high risk for poor adherence can help in interventions to improve adherence. These interventions can be educational interventions. Education may take the form of individual instruction or group classes. Effective interventions can be behavioral approaches that use techniques such as reminders, memory aids, and synchronizing therapeutic activities with routine life events (e.g., taking pills before you shower or after your prayers) [23]. Effective interventions seek to enhance adherence by providing emotional support and encouragement. It should be remembered that the application of multiple interventions of different types is more effective than any single intervention [16]. It is of utmost importance to discuss the impediments faced by each patient and to work together as partners to overcome them. It is only then that the full benefits of adherence and the effective control of blood pressure will be achieved [20].

In this study, blood pressure control level was associated with adherence behavior. Those with controlled blood pressure were observed to be adherent. This finding is in line with other studies [5,15]. It might be attributable to a better outcome of the treatment; this may offer the patient good satisfaction and create a strong motivation toward the treatment. However, a bad outcome (uncontrolled BP) could make the patient hopeless and has a low satisfaction level, which may lead them to stop their treatment [21].

5. Limitations

The limitation of this study is that it used a self-report questionnaire to assess adherence; this method has the disadvantages of recall bias and eliciting only socially acceptable responses, and hence, it may overestimate the level of adherence. However, self-reported measures are simple and economical to use and can provide real-time feedback regarding adherence behavior and potential reasons for poor adherence [5].

6. Conclusions

More than half of the study participants were found to have low adherence. This means that for many hypertensive patients, medication adherence needs to be improved. A number of associations were identified between patient factors and adherence to antihypertensive drugs. These findings may be used to identify the subset of population at risk of poor adherence who should be targeted for interventions to achieve better blood pressure control and hence prevent complications.

Better patient education and communication with health-care professionals could improve some factors that decrease adherence, such as forgetfulness and dissatisfaction with treatment.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks The Palestinian American Research Center (PARC) for funding this study and Professor DE Morisky who gave the permission for use of the ©MMAS-8 in this study.

References

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Rowa’ Al-Ramahi PY - 2014 DA - 2014/06/21 TI - Adherence to medications and associated factors: A cross-sectional study among Palestinian hypertensive patients JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 125 EP - 132 VL - 5 IS - 2 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2014.05.005 DO - 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.05.005 ID - Al-Ramahi2014 ER -