Global Health Diplomacy: Between Global Society and Neo-Colonialism: The Role and Meaning of “Ethical Lens” in Performing the Six Leadership Priorities

- DOI

- 10.2991/j.jegh.2017.11.002How to use a DOI?

- Abstract

Establishing indicators oriented towards the creation of a global society to the detriment of new forms of neo-colonialism. In the relations between Developed and Emerging Countries as part of the Global Health Diplomacy, there is a risk that the former can adopt behaviors induced by the financial needs of overcoming their crisis. The most relevant Documents by International Organizations and Articles published in the past regarding actions in this area and the forecast of economic growth in various areas of the World are considered and the hypothesis of dual scenarios that may arise from these are postulated. There are two hypothetical scenarios arising from the “six leadership priorities”: the search for a Global Society or initiating forms of neo-colonialism on the part of developed countries towards emerging ones. If the “economic lens” is to prevail then the developed Countries, would seek to charge their crisis to emerging Ones where a forthcoming significant growth has expected; if the “ethical lens” is to prevail, it will be most likely be the hypothesis of a Global Society where there is a respect of Human Rights in order to drive growth and harmonization of relations between Governments.

- Copyright

- © 2018 Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The principles, strategy and working assumptions contained in the proposal policy, Health in all policies [1], the Oslo Declaration [2] and the United Nations Resolutions arising from the Report presented in 2009 by the Secretary-General [3] represent the three pillars of Global Health. So far this is characterized by actions in the health sector in favor of low and middle-income rises increases to a more complex vision that fits the issue of Global Health, in an area of international relations between Governments and integrating them with their issues of foreign policy. This strategic positioning, already “in a nutshell” in the definition of Kaplan and Merson [4], gives full expression to the concept of Global Health Diplomacy (GHD) “to describe the process by which government, multilateral and civil society actors attempt to position health in negotiations foreign policy and to create new forms of global health governance” [5] whose ultimate goal is the liberation from poverty and reducing inequalities. This vision has created high expectations and contributed to the development of the activities of Consortia (Global Health Council, CUGH), private groups (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) [6] and other institutions [7] that have produced projects and actions (mainly in the field of education), design and the development of health systems, as well as on-site support to the fight to communicable diseases, but without affecting changes in the relations between high and low income countries. This latter aspect, in fact, should be the goal of governments, but from the generality of governments these principles have not started projects but have been filed more as statements of intent or good intentions, making clear their disinterest in which there is no context that could support economic return [8]. In 2014, the Twelfth General Programme of Work of the WHO [9] and Report of the Secretary-General of the UN in the Sixty-nine Session of the General Assembly [10] gave a fundamental contribution in identifying and structuring the objectives and the means of intervention and partnership for the implementation of activities under the principles of GHD indicating the “six leadership priorities” on which to focus energy and resources. The management of energy and resources, however, can be inserted within an ethical or otherwise new form of colonialism, depending on whether: a) they favor rights and the growth prospects of the beneficiary countries of such energy and resources or b) the benefits that they can generate are used to achieve a return useful in overcoming the crisis of the most powerful countries.

2. METHODS

Taken into account were documents and press articles, extracted from search engines (key words Global and Health and Diplomacy) and the websites of international organizations engaged in the Global health issues that have most determined prospects and lines of action of the higher-income Countries (HIC) to support the cultural and economic growth and, above all, the recognition of fundamental rights such as healthcare, of the low and middle-income countries (LMIC). The two scenarios of ethical (health lens) and colonialism (economical lens) are then considered and discussed to make a working hypothesis that, starting with health issues can meet the needs of some (LMIC) and the expectations of others (HIC).

3. DISCUSSION

By documents considered before arises the issue that the global economic crisis has led governments to contract their balance sheets excluding to take action on health issues where they considered there was not an economic advantage, thus laying in a subordinate position the ethical principles underlying the actions related to the assumptions of GHD.

Ultimately while they claimed principles of solidarity and support for a greater global equity and universally shared statements of intent were made, coming to hope for a “Health lens” as a filter for the evaluation of actions [8] it was once again the economic interest, or rather the lack of it, to lead the decisions of the governments of the high-income countries. Indeed, the same crisis, which involved mainly the high-income countries put them in front of the need to find new markets and new incentives to return to growth.

Attention was then focused towards low-income countries, but has also given rise to a reasonable suspicion that this attention was not supported by the desire to offer cooperation or support on the basis of international principles and beliefs of subsidiarity but to see if it was possible to charge to the latter its recovery. One of the channels through which to develop this hypothesis might just be the GHD but done at the cost of distorting the ethical assumptions. We take into account the recent report by the IMS Institute which shows an increase of about 30% in global spending on medicines that will reach 1.3 trillion dollars by 2018, and that Spending on medicines in Pharmerging Markets will rise more than 50% over the next five years [11], and the FAO Unger map 2014 [12] and overlap them on the map of Pharmergin Markets: there are evident, even surprising, geopolitical interests match. If we then consider the data published by the ECB [13] about the prospects and timings of growth of the economies of emerging countries and those contained in the World Economic Outlook [14], and it overlaps with the previous map, you get a final map that identifies two groups of countries: on the one hand the countries that will be involved in the next few years in both a huge potential growth and simultaneously a high need for support in its own issues of GHD and on the other hand the high-income countries, in crisis, that retain the ability to offer and export innovation, technology, and training. In summary, it outlines the global map of a promising new market that includes a portion of the population above 80% of the world whose actors are represented on one side by the developed countries in search of new sources to support its recovery and on the other hand those emerging and low and middle-income countries in a tumultuous and disorganized growth that need to be supported by importing know-how, technology, and the global system of civil organization besides health. In the report of The Lancet Commission [15] they highlight the “economic value of the health improvements” by identifying in terms of added value the advantages of reduced mortality and improved health resulting from coordinated actions between the developed and emerging countries: this added value must be considered in economic terms, of overall well-being, of more opportunities to develop relationships favorable to growth, of intervention sectors and of the opportunities that each of these is able to provide for both groups of countries. This value of the relationship between health and economic growth is referred to as “full income” identifiable as a new parameter for evaluating the overall productivity of the actions carried out under the GHD. Faced with this possible strong revival of activity, expectations and prospects for growth and return to healthy investment, a cultural context has emerged in which the belief that health as well as trade, investment, the environment and security is part of the global governance process [16]. It is hoped that not only consortia and foundations, mostly private, but also the diplomatic community [17] will be active, giving concreteness to the GHD that had left on standby. Stimulated in doing so from the operational conclusions and objectives set out in the “six leadership priorities” that represent the point of arrival of long-standing cultural debate as well as the new starting point for new actions to which governments are called, what still is not explicitly known are the motivations and the indicators that define the possible return to developed countries who decide to engage in this way: it is just based on what motivations and evaluation indicators related to them will prevail that we can delineate two hypothetical and opposite scenarios.

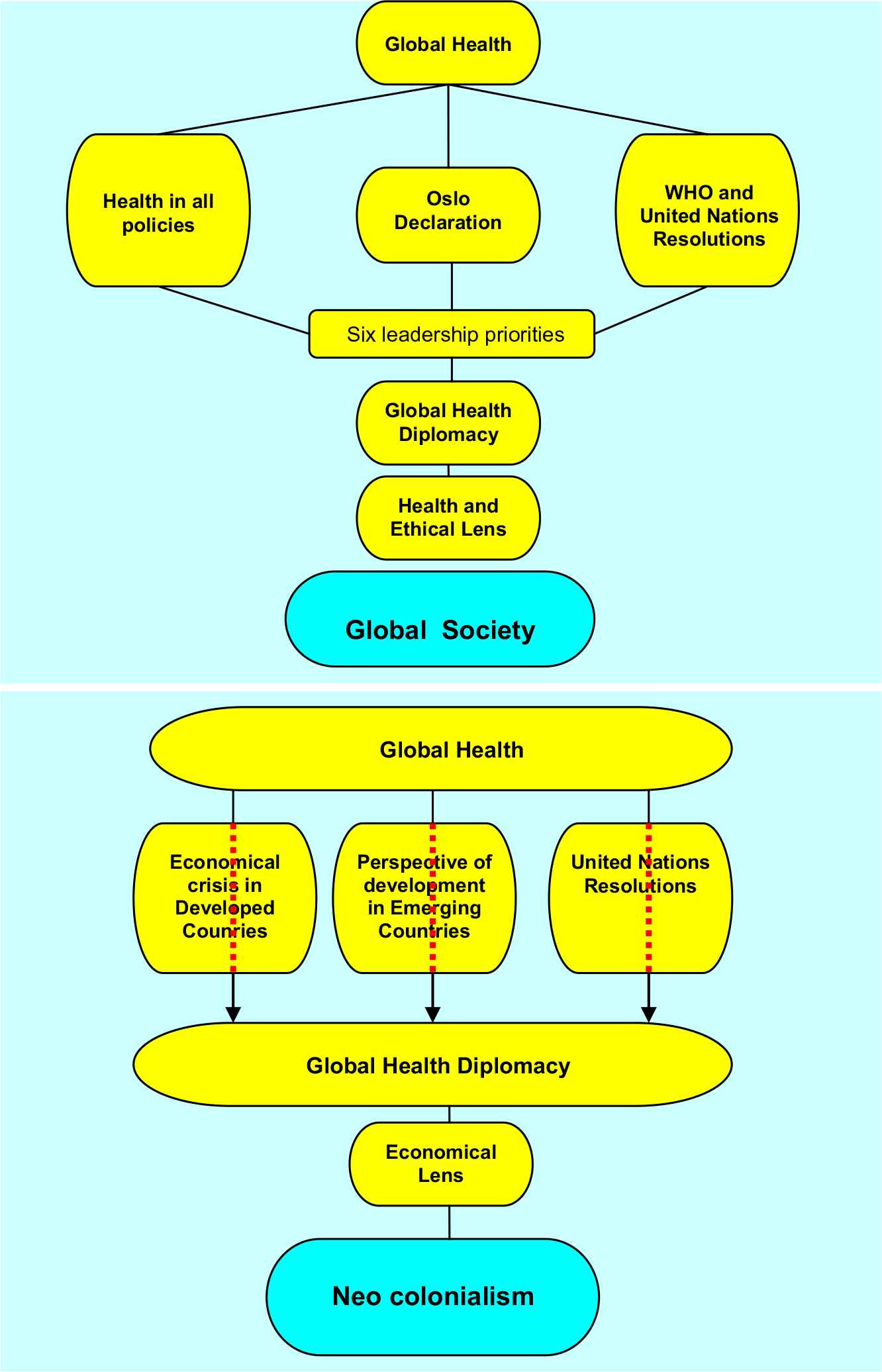

The first could be called the Global Society [18], where actions are performed by the GHD, and are implemented through the “Health lens” whose focal point is made by an “ethical reasoning”, and a second scenario that could be called “Neo colonialism” where instead the GHD is guided by an “economical lens” whose focal point is made up of free market and cost effectiveness rules (Fig. 1).

a) Scenario Global Society. The evolution of the meaning of Global Health produces documents that lead to the Global Health Diplomacy by passing through the six leadership priorities: this uses the “Health and ethical Lens” to give life to the Global Society. b) Scenario Neocolonialism, The Global Health passing through the global economic events (crisis and growth prospects and the documents of the UN) gives birth to a Global Health Diplomacy that uses the “Economical Lens” to give body to neocolonial actions.

In the first case, the fundamental actions in favor of countries covered by the GHD concern a) the six leadership priorities as well as the globalization of medical science as argued by Unter and Fineberg [19]; b) training, which must be made up of a “Relevant educational programs integrated perspectives from cultural antropology, psychology, economics, engineering, business management, policy, and laws, instead of focusing only subjects traditionally taught in schools of public health and medicine, as argued by Merson [20]. In addition, the content of such programs must be addressed to” accelerate the transition of learning from information and training to transformative “as argued by Cris and Chen [21] and thus to the creation of a new local ruling class. The real challenge of developed countries towards the emerging ones will therefore be the choice of an “ethical lens” as a filter of addressing their own actions and, as argued by Kevany [22], for the adoption of a global health program design that explicits the intimate interconnection between health and non-health security with a resource alignment to these programs (“smart power options”): c) the choice of the option that replaces military power with global health in the composition of conflicts demonstrating this interconnection where development and security are weapons of diplomacy and not of war, and thus recognizing global health as a key instrument of peace and stability available to Governments [23]: in other words, to create structures and patterns for the development, training courses addressed to create a new leadership capable of driving itself in a process of transformation of the health system in the context of a transformation of the social order and the internal repositioning of the civil societies of emerging countries in the global context. In this scenario the GHD, will be used, under the guidance and coordination of WHO, for the sharing of knowledge, technologies and the creation of a new generation of local experts. The latter will drive the growth of their countries with a return to developed countries arising solely from their inclusion in a new market, but of which they will not be the only ones to determine the rules: developed countries will be Partners “inter pares”. In this way it would be explicit that the ultimate goals are the fight against poverty and to the inequalities in a context of a guarantee of Human Rights (Global Society). This is the indispensable basis for any type of sustainable growth.

In the second scenario, the action of Governments will be guided by the need to create new markets, the most deregulated possible, in order to encourage the entry of companies or organizations of technology transfer or knowledge at various levels. In this scenario, the Developed Countries will use diplomatic relations to transfer innovations and transformations that Emerging Countries aspire to determine in these, new needs and new demand for knowledge, technology and well-being, but without giving them any real support to a real growth. In this case the satisfaction of Human Rights will remain a formal statement which does not follow concrete actions. The challenge, therefore, will not be addressed to the creation of a class of politicians and technicians capable to lead a business plan, or of development of agriculture or even to give birth to a healthcare system that can provide answers to the welfare needs of the local population; a scenario where the supply of medicines and/or vaccines and projects for the creation of structures to combat diseases like HIV or Ebola, but also malaria or dysentery, or to reduce infant mortality will be decided and proposed by developed countries according to their conveniences, these will be individually set. The creation of a free market or the chance to access information and knowledge has no positive value in itself; in contrast, it can produce huge distortions especially in areas not yet regulated, if not accompanied by ethical rules, democratic forms of government, the development of its own industrial fabric, a system of redistribution of wealth and a health system under local guide ensuring – through the availability of adequate infrastructure – health coverage to as many people as possible. In this scenario, then, will once again the developed countries to dictate rules and timings of implementation of growth projects and training, and, above all, to be the biggest beneficiaries of the actions undertaken under the umbrella of the GHD. In this way they would be able to obtain new resources resulting from a growth of others; resources that, instead of being reinvested locally, will contribute to the recovery of their economies so markedly affected by the crisis, passing by the historic “paternalistic philanthropy” [16] to a real neocolonial system. If these are the two scenarios by which you will be able to develop the “six leadership priorities” within the GHD, is finally necessary to identify or at least assume what will be the rules that will support the scenario of ethics compared to the neocolonial one and the possible benefits which governments that promote them could take (Table 1), identifying economic parameters of incentives such as, e.g., the deduction of investment by the amount of the debt. The management of the entire process by a World Organization recognized by governments, such as the WHO, is the indispensable element together with a rewarding system that materializes the ethical objectives that characterize the projects and the governments that support them.

| Key Work | Framework | Actions | Aims | Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics of the challenge | Structural projects and/or training useful to economic and the health system growth | Governance of projects by a World Organization recognized by Governments (WHO) | Incentive to governments based on the ethical objectives | Accreditation by the International Economic Organizations |

| Ethical objectives | In support of Emerging and low and middle income countries | New partnerships between states | Creating local growth and wellness | Increased health and social well being |

| Implementation | Through existing channels regulated by international agreements | Consortia between states and private or mixed organizations | Participation of Personnel trained on site | Structural relapse in the host country |

| Projects quality control | Administered by the management Agency and independent third parties | Creation of evaluation committees of independent local experts | Consolidation in the time of project outcomes | Based on the parameters of ethical evaluation and effectiveness |

| Measurement of incentives | Established by an international organization recognized by Governments | Determined on the basis of ethical parameters | Delivered in economic terms (revaluation of debt or the ratio of debt to GDP) or participation in projects or consortium of international collaboration | Periodic review of the parameters and rules |

| Future prospects of work | New treaties among states and research projects on the topic | Setting of the weight and value of the indicators | Translation of the weights and values in incentives for governments | Audit for the review and results and incentives’ accountability |

The issues of characterization of actions towards the Global Society through the Global Health Diplomacy

In this sense, the parameters to be considered that define the “ethical lens” are: a) the innovative value, b) the ability to create conditions for local development, c) indicators of growth and welfare, d) the creation of on-site venture, e) research centers, f) health management systems, g) new industrialization, h) establishment of relations and new treaties between states, i) achieving tangible results in the control and combating of communicable and non-communicable diseases, j) availability not only to share knowledge but also on technology for their use in health, k) defining the share of investment in emerging countries aimed at creating local personal, technical, and structures helpful to the growth of the country, and more. Then there will be these ethical parameters to determine the share of incentive for Governments directly involved in collaborative programs within the GHD.

4. CONCLUSION

It will not be easy to achieve such a goal, indeed. However, it is a possible target.

The Documents of the WHO and the UN have identified channels, policy areas and actors, both Institutional and private. The next step is the motivation of governments and the possible economic returns: both must be ethical, the only possible basis for founding an alliance of governments that have the objective of creating a global society that takes place through a GHD definitely subtracted to neocolonial suggestions.

DISCLAIMER

Article type: I have no support in the form of grants or any other form.

I have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Michele Rubbini PY - 2018 DA - 2018/12/31 TI - Global Health Diplomacy: Between Global Society and Neo-Colonialism: The Role and Meaning of “Ethical Lens” in Performing the Six Leadership Priorities JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 110 EP - 114 VL - 8 IS - 3-4 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/j.jegh.2017.11.002 DO - 10.2991/j.jegh.2017.11.002 ID - Rubbini2018 ER -