The African Continental Free Trade Area: A Historical Moment for Development in Africa

- DOI

- 10.2991/jat.k.211208.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- AfCFTA; intra-Africa trade policy integration; UNECA

- Abstract

This policy piece surveys the potential of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) as a historical framework for setting Africa on the path toward structural transformation and sustainable development. After evaluating the part that the landmark continental trade integration reform will play in rebuilding better from the pandemic, the paper quantifies the trade-related impacts of the AfCFTA and assesses its contribution beyond trade. It also highlights Economic Commission for Africa’s ongoing support to implementation, building on the support the commission has historically provided to regional and continental integration in Africa.

- Copyright

- © 2021 African Export-Import Bank. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The signature of the Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) by 44 African Union member States at the 10th extraordinary meeting of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union, held in Kigali on 21 March 2018, marked a momentous milestone for economic integration in Africa.1 On 1 January 2021, after some 5 years of technical efforts since the official launch of negotiations in June 2015, this outstanding political accomplishment bore fruit in the official start of trading under the Agreement. The first consignments of goods traded under the AfCFTA—containers of cosmetics and drinks from Ghana to South Africa—were reported to have shipped by 5 January 2021 (Daily Graphic, 2021). As of July 2021, 40 African countries had ratified the AfCFTA.

This achievement crowns a vision of continental trade integration that is over 50 years old (Gérout et al., 2019). In 1963, the Summit Conference of Independent African States, the inaugural meeting of the Organization of African Unity, appointed a ‘preparatory economic committee to study … the possibility of establishing a free trade area between the various African countries’.2 Previous continental integration attempts have all failed, however. Surveying the missed opportunities of African integration among the economic crises of the 1980s, Adebayo Adedeji lamented that ‘when a state finds itself in a crisis, it does not see beyond its nose’ (Adedeji, 2002). It is all the more commendable therefore that the African continent achieved the official commencement of trading under the AfCFTA less than 10 months after the World Health Organization declared the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic, a blight on global development and prosperity that will be remembered for centuries.3

It is no under-estimation to say that ECA has been one of the foundational proponents and supporters of the AfCFTA, and African economic integration in general, going back to the very first meetings of ECA in the late 1950s.

Under the leadership of Adebayo Adedeji, from 1975, ECA proactively led in initiatives such as the Lagos Plan of Action and the establishment of the RECs (Gérout et al., 2019). ECA research on the rationale for a continental trade agreement in 2010 foreshadowed the AU’s Boosting Intra-African Trade Action Plan in 2012 that formally envisaged for the first time a ‘continental free trade area’.4

A centre-piece of the intellectual groundwork contributed to integration by ECA has been the Assessing Regional Integration in Africa (ARIA) report series, produced in partnership with the AU and African Development Bank (AfDB) since 2004. The ARIA series have notably built the case for REC rationalization (2006), an African continental trade agreement (2010), the political economy for realizing the AfCFTA (2017) and the effective implementation of the AfCFTA and its phase II protocols (2020), among other contributions to economic development issues on the continent.

At the sub-regional level, ECA has assessed the particular dimensions of the AfCFTA in relation to the Eastern Africa region (ECA and TMEA, 2020). In ensuring that the AfCFTA would be pro-development, ECA led in 2017 a human rights impact assessment of the AfCFTA (ECA et al., 2017). And in 2017, ECA first made the case for including e-commerce and the digital economy as an additional protocol to the AfCFTA, in a briefing note to the African Union Commission (AUC), a decision that would eventually be made by African Heads of State and Government in 2020.

ECA also has had a privileged role in supporting the AfCFTA negotiations directly. The AU Assembly, in its 2015 decision launching the AfCFTA negotiations, called upon the ECA, AfDB and Afreximbank ‘to provide the necessary support to the member States, the Commission and the Regional Economic Communities to ensure a timely conclusion of the Negotiations’.5 The role played by ECA, and the other technical partners in the negotiations, goes well beyond their participation in the meetings of the AfCFTA negotiating institutions. The channels of influence and contribution to the AfCFTA negotiations process range from the analytical work they produced, the technical support they provided to member States and their negotiators, to the AU Commission and related continental organs, as well as to RECs and their Secretariats.

Africa has much further to go, however. Having ‘seen so many proclamations remain a dead letter’,6 in the words of Moussa Faki Mahamat the Chairperson of the African Union Commission, and recognizing that the ‘AfCFTA is going to be difficult’,7 in the words of Wamkele Mene the Secretary General of the AfCFTA Secretariat, the focus must now turn to ensuring that the transformative potential of the AfCFTA is actualized.

The present article surveys the role of the AfCFTA in rebuilding the economy of Africa to better serve the developmental goals of the Agenda 2063 of the African Union and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. It also presents an account of the role played; both past and present, by the Economic Commission for Africa in the AfCFTA process.

2. ROLE OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA IN REBUILDING BETTER FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a significant and possibly long-lasting blow to African economies. Growth in Africa contracted for the first time in more than 20 years, declining by 1.9% in 2020 (IMF, 2021). The continent’s fiscal deficits are estimated to have almost doubled, from 4.7% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2019 to 8.7% in 2020 (ECA, 2021a).

As a consequence, Africa does not have the fiscal space to replicate the multi-trillion-dollar stimulus initiatives of some of the world’s richest countries: for example, the stimulus measures enacted by the United States alone, measuring $6 trillion as of May 2021, exceed twice the size of the entire annual GDP of Africa (Statistica, 2021). Africa must instead look to more creative measures for its recovery.

Deepening regional integration through the AfCFTA initiative can support a restructuring of Africa’s recovery from the pandemic to rebuild an African economy more conducive to achieving the goals laid out in Agenda 2063 of the African Union and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The COVID-19 crisis has already catalysed such a reordering of global supply chains for greater resilience and production on the continent (ECA and IEC, 2020). The role of the AfCFTA is to build on and accelerate this process of industrialization and diversification of sources of growth and exports.

The creation of the AfCFTA provides a means of leveraging the combined economic size of Africa, fostering export diversification and industrialization and coordinating African trade policy. The AfCFTA also offers an invaluable opportunity to accelerate the twin digital and green transitions which are central to building forward a more sustainable economy.

2.1. Leveraging Africa’s Economic Size

Africa accounts for one-sixth of the world’s population but is fragmented into 55 member states of the African Union. Many are too small to support economies of scale and attract the investments necessary for industrialization and sustainable growth: 22 countries have populations less than 10 million. Businesses face average tariffs of 6.9% when they trade across the continent’s 107 inter-State land borders, but also substantial Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs), regulatory differences and divergent sanitary, phytosanitary and technical standards that raise costs by an estimated 14.3%.8 The AfCFTA seeks to integrate and consolidate Africa into a $2.5 trillion market of 1.3 billion people.

2.2. Diversifying and Industrializing Exports

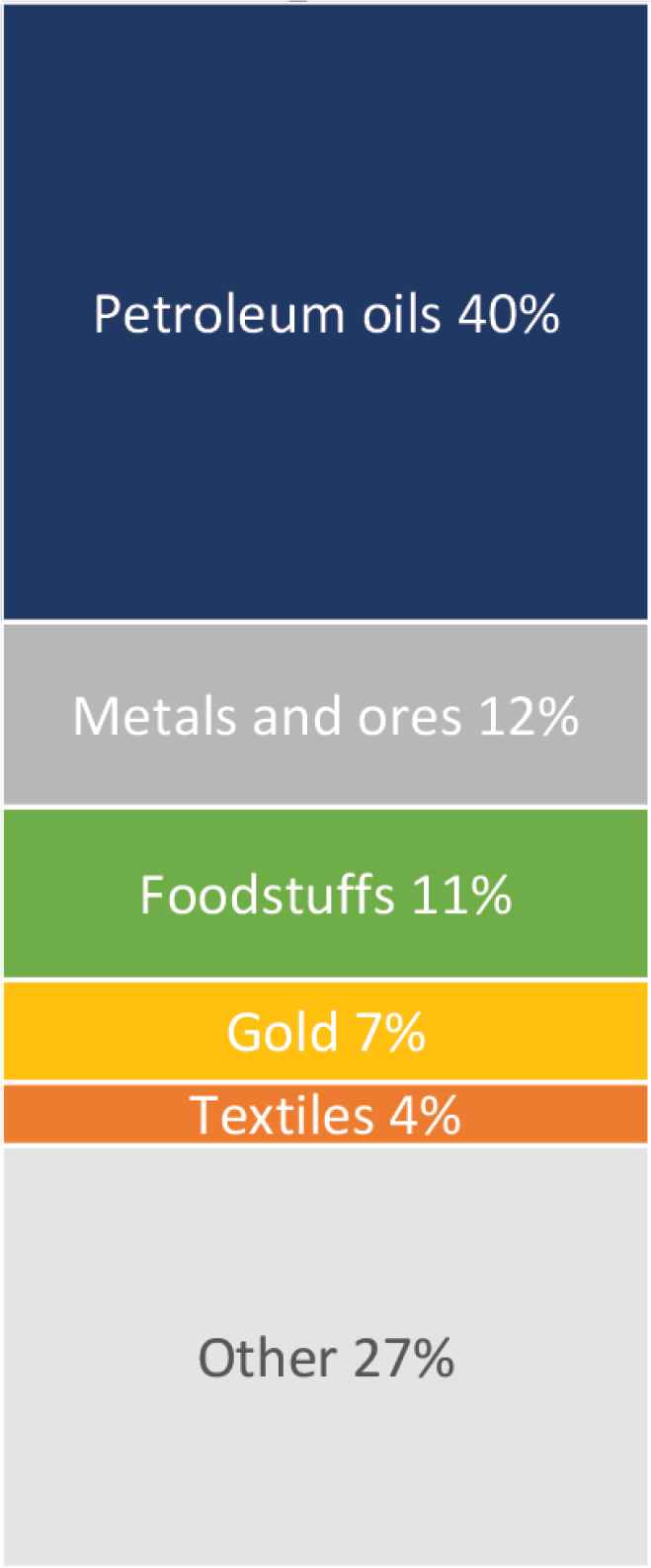

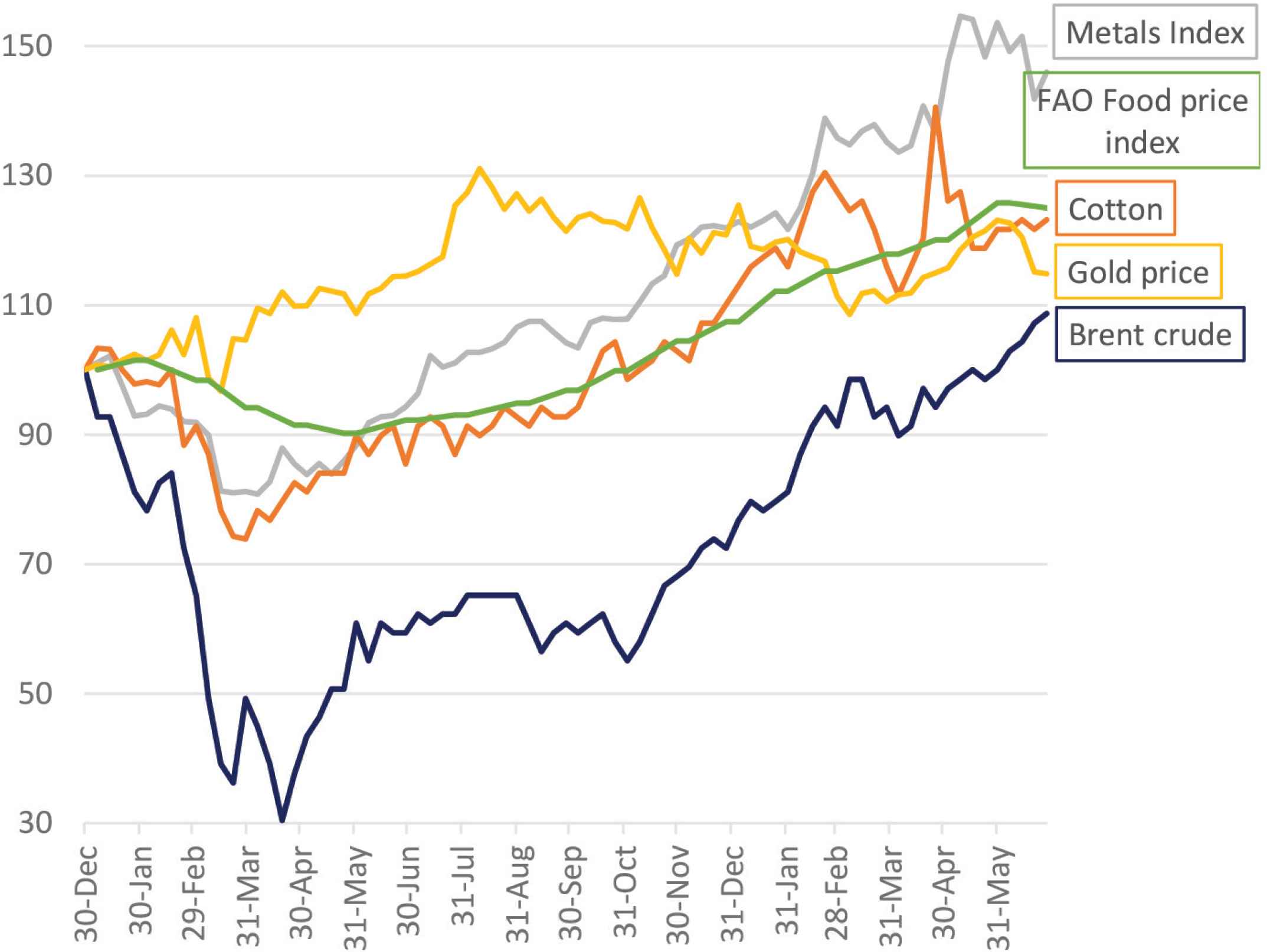

The global economic crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic has already had a relatively predictable impact on trade in Africa: commodity prices fluctuated considerably and with them the continent’s foreign exchange, fiscal revenues and economic stability. Most sectors crashed before rebounding strongly in the latter half of 2020 into 2021 (Figures 1 and 2).9

Composition of African exports. Source: Based on data from the International Trade Centre, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Trading Economics data platform, June 2021. Notes: Metals Index is the London Metals Exchange Index. Cotton prices are included as a very rough proxy for textile prices. Composition of African exports based on a 3-year average from 2016 to 2018.

Price developments for top African exports, December 2020 to June 2021. Source: Based on data from the International Trade Centre, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Trading Economics data platform, June 2021. Notes: Metals Index is the London Metals Exchange Index. Cotton prices are included as a very rough proxy for textile prices. Composition of African exports based on a 3-year average from 2016 to 2018.

The cumulative result was Africa’s total exports falling 16% in the course of 2020, with those from oil-exporting countries falling 40%, as compared to 2019. Africa’s gold exporters, on the other hand, saw an 18% increase in export values.

This volatility reflects the limited diversification of trade: petroleum oils, metals (manganese, aluminium, copper, chromium, palladium and others) and gold together account for almost 60% of total exports from Africa. Intra-African trade presents a different configuration: these commodities account for a far lower share (about 30%) of trade within the continent. Instead, manufactured products account for a much larger share of intra-African trade (about 40%, as compared to only 20% of exports to the rest of the world).10

The use of the AfCFTA as a pivot to intra-African trade will thus provide a more secure source of revenues and foreign exchange, less dependent on the fluctuations of commodity prices. It will also catalyse the trade in manufactured products needed to support the long-overdue industrialization of Africa. Industrialization is the tried and tested engine for economic development, historically contributing to secure middle-income status, broader tax bases and diversified export baskets.

2.3. Coordinating Trade Policy

Integrating the African market will help the continent to engage coherently in trading arrangements with the rest of the world. The United States of America, the European Union, emerging market economies and others are looking to establish trade deals with Africa. To use the language of Agenda 2063, in pursuit of ‘the Africa we want’, Africa can achieve more if it will ‘speak with one voice and act collectively to promote our common interests and positions in the international arena’ and affirms the importance of ‘unity and solidarity in the face of continued external interference’. With a single voice, Africa can negotiate trade deals better than individual countries alone.

An example can be drawn from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) group of 10 Southeast Asian countries. As a group, it found itself more attractive to partners seeking trade agreements, providing the impetus for negotiating various ASEAN+1 agreements (Mikic and Shang, 2019). The consolidated economic size of a country grouping in negotiations makes it more attractive to partners, while also giving it more economic clout with which to press for more preferential negotiated outcomes.

Coordinating African trade policy with partners can also better ensure that agreements with third parties do not contain provisions that might undermine regional trade. A counter example here has been the interim Economic Partnership Agreements between individual African countries and the European Union which have frustrated the effectiveness of some of Africa’s customs unions by requiring different tariff schedules between members of these unions.

However, it is also in the interest of outside partners to support African integration efforts so that they are then able to invest in a robust and unified African continent that offers greater consolidated opportunities.

2.4. Aligning Digital and Green Transitions

Before the pandemic, digitalization was poised to change the world. COVID-19 marks the historic tipping point into the digital era. Stocks of the so-called ‘big tech’ concerns (Apple, Amazon, Tesla, Microsoft, Alphabet, Facebook and Netflix) increased in market value by more than 50%—equivalent to $2.5 trillion—over the course of 2020. In Africa, 61% of a sample of firms surveyed by ECA reported an increase in online sales since the outbreak of the pandemic (ECA, 2021b), while another ECA and IEC survey found that 75% of businesses in the goods sector and 61% of micro-sized enterprises identified online selling as a top new opportunity in reaction to the crisis (ECA and IEC, 2020). Financial statements data from African digital firms indeed suggest some degree of digital acceleration in Africa in the course of COVID-19, with Nigerian data consumption reported by MTN Group Ltd. up 33% in the first half of 2020, for instance (ECA, 2021c).

Yet, considerable challenges and inequalities persist in the African digital economy. Only a minority—some 29%—of Africans currently use the internet (International Telecommunication Union, 2021); online payment options are generally limited, with most consumers preferring cash on delivery (ECA, 2021c); and, according to a survey of firms by ECA in 2020, low online trust is reported to be the topmost challenge constraining e-commerce (ECA, 2021b). It is however important that in improving the digital market in Africa, African countries do not merely facilitate a market for e-commerce and digital imports, but also digital value creation on the continent. There is some evidence that suggests that while digitalization can improve the efficiency and market access of African small- and medium-sized firms, it can also risk consolidating control in lead firms outside of the continent (Foster et al., 2017). The most important guard against this is in improving digital literacy and skills on the continent.

In January 2020, the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union announced negotiations for a protocol on e-commerce to the Agreement Establishing the AfCFTA. This protocol will give the AfCFTA an opportunity to respond to some of the requirements of building an effective digital economy in Africa. In an ECA-supported survey of small- and medium-sized African businesses in 2020, when asked how the AfCFTA could help support their cross-border e-commerce, the priorities identified were in creating harmonized digital economy regulations in areas such as taxation, online consumer protection and electronic trade (ECA, 2021b).

The second major economic transition that Africa faces is in the area of the environment. In 2019, African countries were already spending between 2% and 9% of their GDP in responding to climate events and environmental degradation, such as storms, floods, droughts and landslides (World Meteorological Organization, 2020). The world’s environmental emergencies are as pressing as ever, even if they may seem distant during the COVID-19 crisis. Avoiding the worst impacts of climate change will be key to future resilience and stability in Africa. Most climate change discussions are typically constrained within borders and focused on domestic commitments, to avoid issues of non-discrimination. Yet trade offers enormous potential for climate change cooperation that should not be overlooked. ‘Greening’ the AfCFTA can offer an important platform to deliver progress on climate change. Practical steps here can involve the inclusion of environmental goods and technologies, such as wind turbines and photovoltaic systems, in liberalization schedules as well as prioritizing the harmonization and strengthening of environmental standards and regulations under the African Quality Standards Agenda.

Inaction is a poor option. As the main external markets of Africa rapidly switch to green growth models through initiatives such as the European Union Green Deal, China 2060 and the Biden climate plan, Africa risks being left behind with stranded fossil fuel assets: in limiting global warming to 2°C, as much as 26%, 34% and 90% of the gas, oil and coal reserves, respectively, of Africa may be left unused (Bos and Gupta, 2019). Yet, with 42 of the 63 rare earth elements that are required in low carbon technologies and the digital economy, such as cobalt used in batteries, Africa has opportunities for green regional value chains and products that fit with growing green demand.

3. QUANTIFYING THE TRADE-RELATED IMPACTS OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA

3.1. GDP and Total Exports

The AfCFTA is estimated by ECA to increase both the continent’s GDP and its total exports. Overall African GDP is forecast to increase by 0.5% (equivalent to around $55 billion annually), after full implementation in 2045 and compared to a scenario without the AfCFTA. The choice to present the results in 2045 is justified by the fact that the AfCFTA reform is implemented over time between 2021 and 2035 but also to give enough time for all the variables to adjust following full implementation of the AfCFTA reforms in the model.

Though these overall gains may appear modest in the context of total African GDP, it is how they transform the structure of African trade that is important. The gains are driven by a substantial expansion of intra-African exports by 34% (equivalent to around $133 billion annually), as compared to a scenario without the AfCFTA. Approximately two-thirds of the intra-African trade gains would be realized in the manufacturing sector (Figure 3).

Distribution of absolute gains in intra-African trade, by main sectors, with AfCFTA implemented as compared to baseline (i.e. without AfCFTA)—US$ bn and %—2045. Source: ECA and the Centre for International Research and Economic Modelling (CIREM) of the Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Information Internationales (CEPII) calculations based on Modelling International Relationships in Applied General Equilibrium (MIRAGE) Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model. Notes: The choice to present the results in 2045 is justified by the fact that the AfCFTA reform is implemented over time between 2021 and 2035 but also to give enough time for all the variables to adjust following full implementation of the AfCFTA reforms in the model.

The AfCFTA helps to wean African off an economic structure in which about half of its exports to the rest of the world are energy and mining products of low value-added content but 60% of imports from the rest of the world are industrial goods. It provides invaluable opportunities for the industrialization and diversification needed for development on the continent.

It should also be emphasized that trade gains well may be under-estimated as only formal trade is captured in the analysis, whereas informal trade is believed to account for an additional 11–40% share of intra-African trade (Harding, 2019). Therefore, a non-negligible added benefit from the implementation of the AfCFTA is that through reduction of costs to trade across borders, one can anticipate that informal traders may gradually move toward formal trade which is it becomes less costly and trade operations less cumbersome.

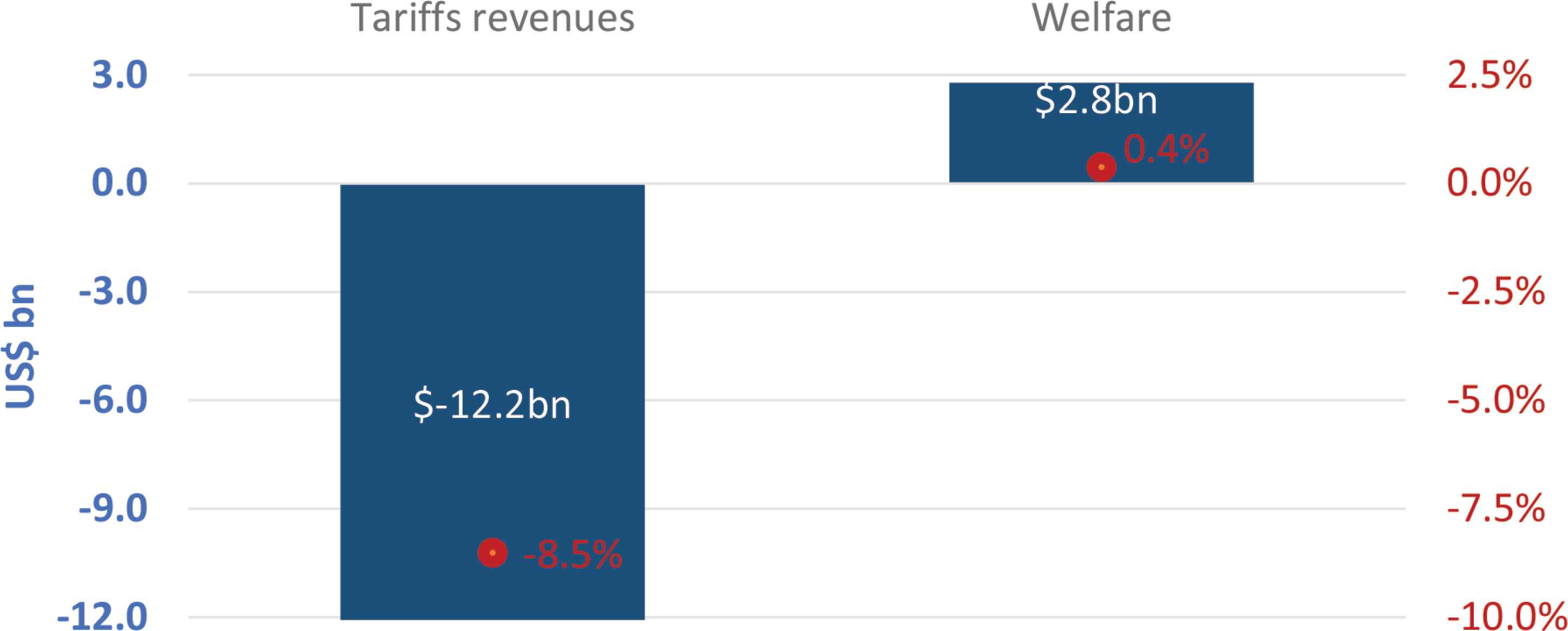

Tariff liberalization entailed by the AfCFTA Agreement would however lower tariff revenues by an estimated 2.9% (or $2 billion) in 2025 and by 8.5% (or $12.2 billion) by 2040 (Figure 4). Although this is not negligible, it is not a gigantic loss either for the continent as a whole and is dwarfed by the expected $55 billion increase in GDP (and $133 billion increase in intra-African trade). Africa’s least developed economies, in particular, will be able to delay tariff revenue losses most given their more lenient liberalization schedules (which extend up to 2033). Governments also have other sources of revenues at their disposal which could be acted upon to compensate such losses and the Afreximbank has already set up the AfCFTA Adjustment Facility which is to serve as a mechanism to provide short- to medium-term financing to vulnerable countries. Afreximbank has already committed $8 billion with the understanding that additional funds would need to be primarily raised from the markets, as required.

Changes in Africa’s tariff revenues and welfare, following AfCFTA implementation as compared to baseline (i.e. without AfCFTA)—US$ bn and %—2045. Source: ECA and the Centre for International Research and Economic Modelling (CIREM) of the Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Information Internationales (CEPII) calculations based on MIRAGE CGE model.

The full benefits of the AfCFTA will depend to a large degree on the extent to which NTBs are addressed under the Agreement. Those could be multiplied by 2–4, compared with a situation where only tariffs are liberalized and depending on how ambitious the reduction in those actionable non-tariff measures (NTMs) may effectively translate on the ground under the AfCFTA reform. More ambitious cuts in NTMs are also particularly conducive to stimulating industrial trade. More globally, reducing NTMs within the African continent is most important for maximizing the gains beyond trade and in terms of Africa’s GDP, output and welfare.

3.2. Distributional Effects

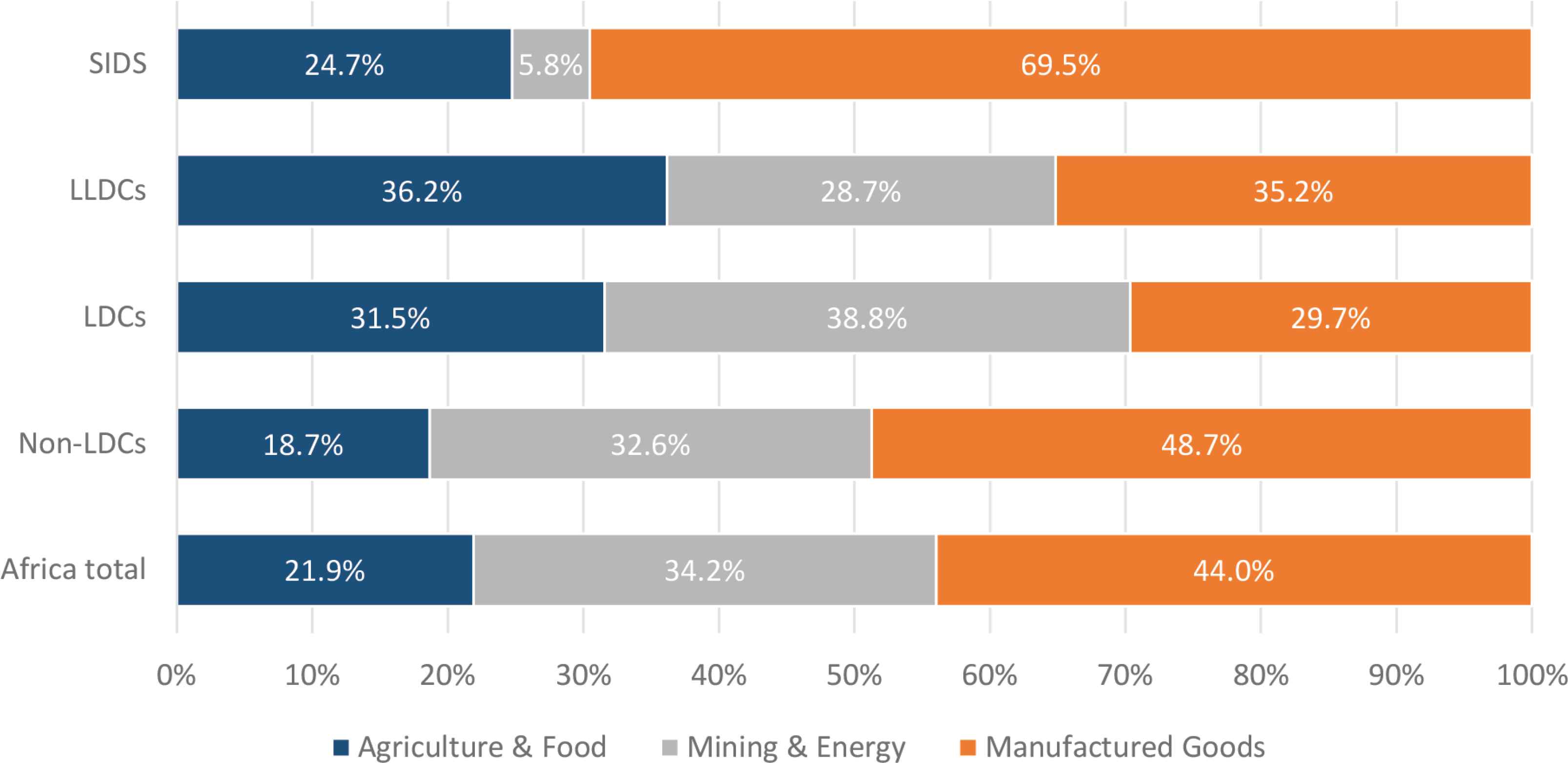

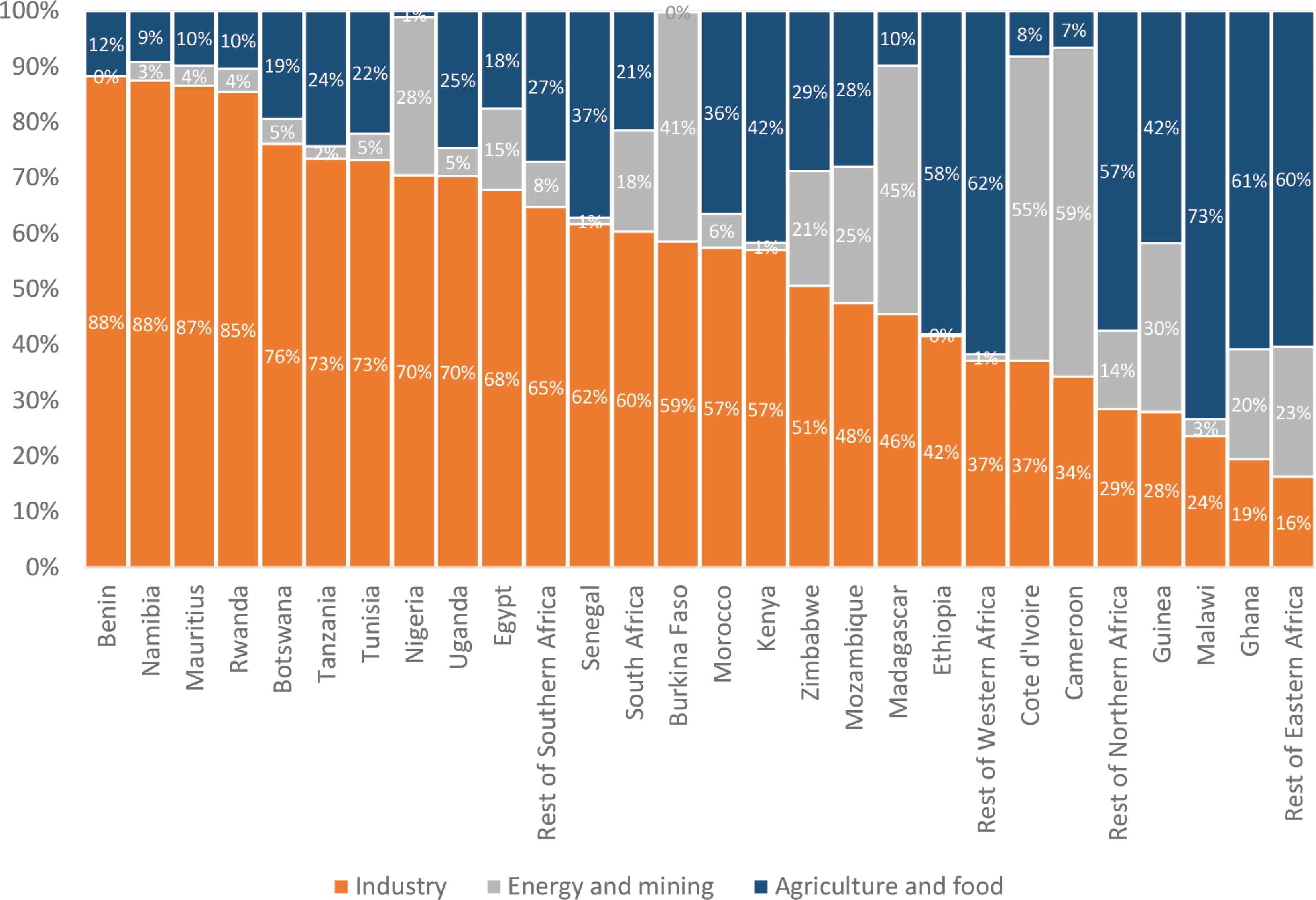

The least developed countries of Africa are also the continent’s least industrialized countries. Manufactured goods accounted for 29% of the intra-African exports of such countries between 2017 and 2019. By disproportionally stimulating the industrial exports of its least developed countries, the AfCFTA will contribute most in helping them to narrow the industrial gap between them and the other countries in the continent (Figure 5).

Sectoral distribution of intra-African exports, by country groupings, 2017–2019 average. Source: ECA calculations based on figures from the UNCTADstat dissemination platform. SIDS, small island developing states; LDCs, least developed countries; LLDCs, land-locked developing countries.

The industrial gains in intra-African trade are not uniform across countries, however. While for most countries the largest share of the benefits is found in the industrial sectors, there are a few notable exceptions. For example, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea and Malawi would see the largest expansion in intra-African trade for agricultural and food products, whereas in Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire this would take place in energy and mining (Figure 6).

Distribution of total gains in African countries’ exports to Africa, by main sectors. Source: ECA calculations based on MIRAGE CGE model. Notes: Results apply an intermediate ambition scenario to the lists of products excluded from the liberalization that is approximately consistent with the level of ambition achieved by the AfCFTA modalities for trade in goods. Results express changes in trade over the longer term (i.e. by 2040) in comparison with a scenario in which there is no AfCFTA. These modelling estimates are from an earlier model than that presented elsewhere in this paper, but which focused particularly on distributional issues, so should be considered tentative.

3.3. Top 10 Sectors

Where the individual sectors are concerned, in terms of agrifood the sectors to benefit most are milk and dairy products, processed food, cereals and crops, sugar. In industry, the sectors with the most potential are wood and paper products, chemical, rubber, plastic and pharmaceutical products, vehicles and transport equipment, metals, other manufactured products, and in energy and mining there is scope for refined oil exports. All of these sectors are forecast to experience an increase in intra-African trade in excess of 30% and not less than $1 billion.

In terms of services trade, intra-African trade would increase by over 50% for financial, business and communication services, by around 50% for tourism and transport and by just over a third for health and education (Table 1). Nonetheless, the opportunities for trade in both education and health services should not be ignored. Indeed, although more modest in relative terms as compared to the five priority sectors, gains would still be considerable in both education and health and in fact gains would even be remarkable in many countries.11 It should also be emphasized that trade in health and education services within the AfCFTA framework, and along with the other five priority sectors, would help somewhat reducing the current heavy dependence of Africa on both exports to and imports from the rest of the world in health and education services. This has become a critical imperative following the COVID-19 crisis, which has further revealed the need for Africa to strengthen its own production and trade capacities in health and education. The two sectors are important vehicles for growth and development and Africa cannot afford missing the trend towards increased digitalization, particularly affecting the education sector.

| Total services | Business services | Transport | Education | Communication | Financial services | Health | Tourism | Other services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US$ billion | 4.4 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| % | 39.2 | 69.6 | 46.6 | 34.2 | 57.5 | 107.0 | 35.0 | 49.9 | –0.9 |

Source: ECA and the Centre for International Research and Economic Modelling (CIREM) of the Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Information Internationales (CEPII) calculations based on MIRAGE CGE model.

Changes in intra-African trade, by specific services sectors, with AfCFTA implemented as compared to baseline (i.e. without AfCFTA)—US$ billion and %—2045

4. AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA BEYOND TRADE

4.1. Poverty Alleviation

Because of the importance attached to poverty reduction in Africa, the expected effect of the implementation of the Agreement Establishing the AfCFTA on income distribution and poverty is of great interest. Most stakeholders involved in the negotiations and implementation of the Agreement expect that it will be accompanied by a reduction in poverty and income inequality on the continent. Several mechanisms can justify the expected effect of the implementation of the Agreement on poverty and inequality. These include mechanisms related to changes in the remuneration of factors of production and the prices of goods and services; the effects on employment levels induced by economy-wide adjustments; and changes in transfers resulting from changes in the incomes of certain economic agents such as the government and firms (Rivera and Rojas-Romagosa, 2007).

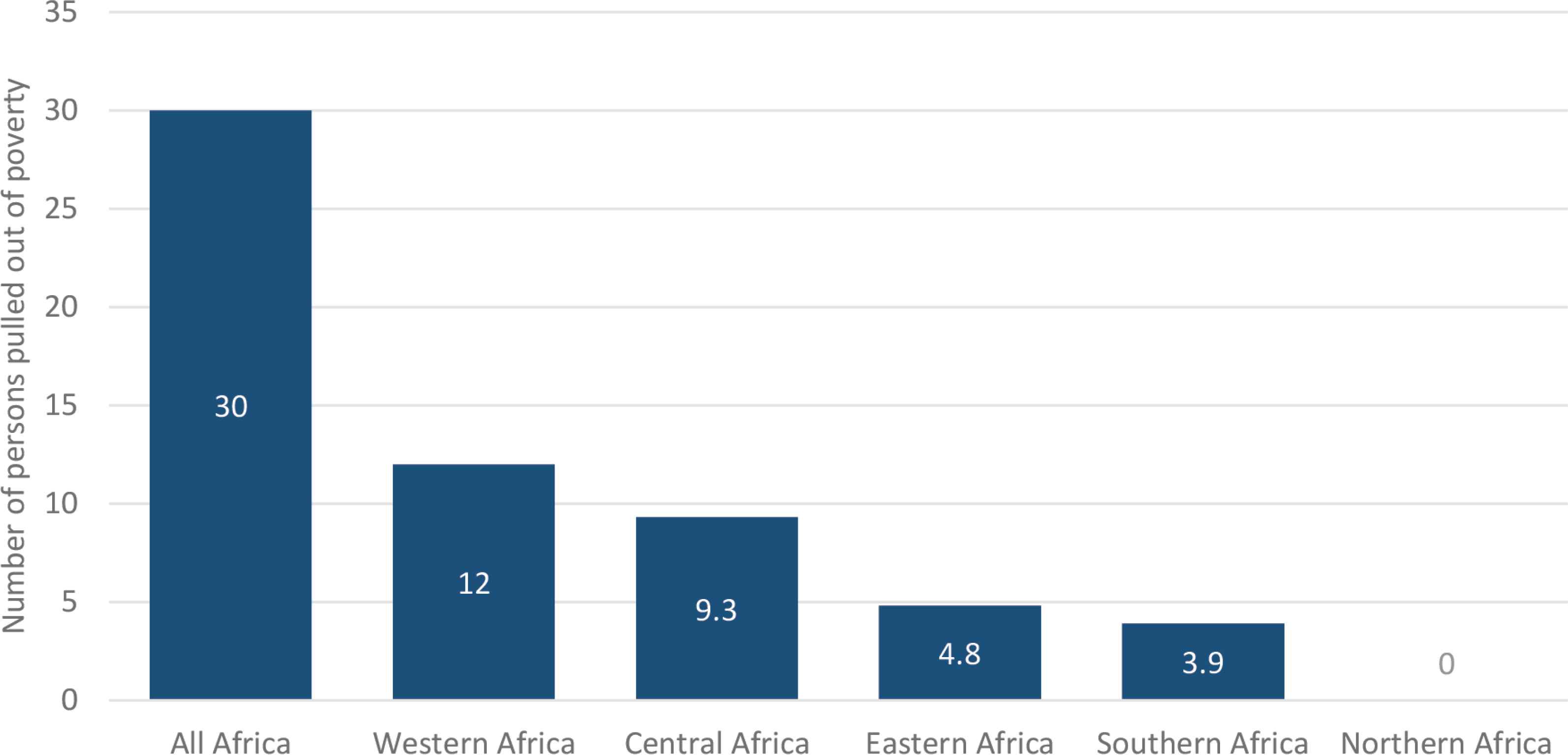

Results from simulations carried out by the World Bank, which include the liberalization of tariffs along with an ambitious reduction of non-tariff measures in Africa and implementation of the World Trade Organization Agreement on Trade Facilitation, suggest that poverty could be reduced across the continent with an estimated 30 million people being lifted out of extreme poverty (World Bank, 2020) (Figure 7). As stated above, however, the true value of the AfCFTA is that it restructures Africa’s economy for the industrialization and diversification needed for longer-term development that extends beyond these modelled estimated; the economic transformative potential for poverty reduction is likely to be even more substantial over the longer term.

Impact on poverty in Africa by 2035, millions. Source: Compilation from World Bank (2020). The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects.

4.2. Gender and Youth Perspectives

The AfCFTA can promote gender equality and women and youth empowerment, fundamentally driving national, continental and global sustainable development outcomes. The establishment of the AfCFTA will create new trading and entrepreneurship opportunities for women across the key sectors of agriculture, manufacturing and services. The boosted demand for manufactured goods will encourage larger export-oriented industries to source supplies from smaller women-owned businesses across borders, while the opening of borders will increase opportunities for women to participate in trade through reconfigured regional value chains and more easily meet the standards of continental markets.

The above-cited 2020 World Bank study on the economic and distributional effects of the AfCFTA, although it includes reforms which go beyond the parameters agreed upon by African Union member States, estimates that the AfCFTA could make small contributions to closing the gender wage gap, thanks to the resulting increases in wages for women (10.5% by 2035), being marginally larger than those for men (9.9%). Employment gains are expected in agriculture, one of the principal sectors driving African economies, in which women represent about half of the labour force. The projected 1.2% increase in employment expected to result from the establishment of the AfCFTA (although small) will also reduce the high levels of youth unemployment, helping to engage some of the continent’s 252 million young people in productive activities. The African Union Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons could help to tackle the skills shortages underlying the under-employment and unemployment of young people. The reduction in the cost of trade will incentivize the creation of small- and medium-sized enterprises for the many young people employed in the informal economy, which accounts for around 90% of jobs in many African countries, and for women working as informal traders, who constitute up to 70% of that sector, through entrepreneurship, e-commerce and trading through formal channels that offer more protection.

Notwithstanding this potential, gains will not be automatic. In order for the benefits of the AfCFTA to be inclusive for women and young people, countries must diversify their exports to build resilience to changes in demand, move to higher-value-added products and services with improved wages, and include small- and medium-sized enterprises in accessing new markets while encouraging innovation and improving productivity. Maximizing the benefits of the free trade area will require an inclusive approach to the implementation of the AfCFTA Agreement. To this end, ECA is supporting the process of gender mainstreaming in the design of national AfCFTA implementation strategies and public–private dialogues to facilitate inclusive implementation of the Agreement. This process is guiding the development of gender-responsive complementary policy reforms to advance women’s full participation in the process of rolling out AfCFTA, and as part of the solution to post-pandemic recovery efforts. Digital approaches to trade facilitation will help to reduce the scope for gender or age-based discrimination. Ensuring equal trade and economic opportunities will ensure that the establishment of the AfCFTA serves as a milestone for inclusive socioeconomic development on the continent.

5. CONTINUING ECA SUPPORT TO THE AfCFTA

Supporting the negotiations leading to the Agreement establishing the AfCFTA is only the first step. The most difficult job is now in translating those negotiated texts into meaningful implementation and sustainable outcomes. With ECA’s rich history of support to regional and continental integration, there is an imperative and a responsibility for continuing support for the effective implementation of the AfCFTA. ECA support in this area spans four main channels: (i) research foundations, (ii) implementation strategies, (iii) operational tools and (iv) complementary initiatives.

The focus of ECA’s work on the research foundations for the effective implementation of the AfCFTA is oriented around sustainability, equitable development and addressing the wider gaps that would prevent effective utilization of the AfCFTA. In appreciation of the pressing importance of ‘greening’ the AfCFTA, ECA has commissioned an environmental impact assessment of the AfCFTA. Following the successful human rights impact assessment of the AfCFTA (ECA et al., 2017), this work will analyze the environmental implications of the AfCFTA while identifying environmentally supportive accompanying measures. ECA’s work on trade facilitation currently involves an ongoing study with the AU to ascertain an optimal customs system for improving trade transit in Africa as well as a customs application to limit human contact for safer trade in the context of COVID-19. In recognizing that services trade, despite its potential, continues to lag in regional integration, ECA’s upcoming Assessing Regional Integration in Africa report in partnership with the AUC and AfDB focuses on services trade in Africa.

ECA’s more forward-looking work in the area of research foundations includes a forthcoming report on an African Common Investment Area, identifying measures to level the playing field for intra-African investment. Appreciating that the relationship between Africa’s RECs must evolve to embrace the AfCFTA, another forthcoming ECA study assesses the governing interface between RECs and the AfCFTA, identifying an ambitious set of recommendations for leveraging the RECs for effective AfCFTA implementation. Finally, an upcoming study looks at the implications of the AfCFTA for the demand of transport infrastructure and services in Africa, anticipating an overall 28% increase in total intra-African freight demand as a result of the AfCFTA and prioritizing investments in critical bottlenecks in Africa’s maritime, road, rail and air infrastructures.

In practice, implementation of the AfCFTA involves the enactment of trade policy at the country level. ECA’s second main channel of support to AfCFTA implementation involves support to 40 African countries or their RECs in the preparation of AfCFTA implementation strategies, 13 of which have now been completed. These strategies use an integrated and participatory approach to bring together private sector actors, civil society organizations, academia and government to identify country-specific AfCFTA market opportunities and required institutional, regulatory or capacity reforms for implementation. Each strategy involves nine key components: a macroeconomic framework, situational analysis, risks and mitigating actions, production and trade opportunities, challenges and strategic measures, strategic objectives and monitoring and evaluation frameworks, financing, communications and visibility plans, and cross-cutting issues. ECA is further working with a selected 10 African countries to provide a detailed analysis of the revenue implications of the AfCFTA and support for new fiscal architectures that focuses on revenue replacements, including through improvements to tax administration.

The third channel through which ECA supports AfCFTA implementation is with the development of operational tools. It is businesses that will actually trade under the AfCFTA and its success relies on its utilization by firms across the continent. Accordingly, ECA has piloted and is now rolling out an AfCFTA Country Business Index to ascertain, from the perspectives of businesses trading in Africa, the remaining obstacles to their trade in the continent and to review the effectiveness of the AfCFTA in addressing their concerns. In partnership with Afreximbank, ECA is developing the African Trade Exchange platform, an online business-to-business marketplace for intra-African trade leads to be established by businesses and supported with logistics and payments options (built on the successes of the African Medical Supplies Platform).

The fourth and final channel through with ECA supports AfCFTA implementation is with complementary initiatives that seek to leverage the opportunities of the AfCFTA. Notable here is ECA’s AfCFTA-anchored pharmaceutical initiative. This focuses on two strategies with high potential in 10 target countries: firstly, opportunities arising from pooled procurement and secondly, the potential for local production. The AfCFTA helps to consolidate a $259 billion health market with the potential to create 16 million jobs and improve health outcomes for Africa’s 1.3 billion citizens if health financing gaps can be strategically overcome and production localized.

The implementation of the AfCFTA will take time as African leaders, policymakers and businesses react to harness its opportunities. Assistance from many angles will be required to ensure that the AfCFTA realizes its transformational potential. As through the history of ECA since its formation in 1958, it stands as an institution ready to provide support to the regional and continental integration initiatives of the continent.

6. CONCLUSION AND WAY FORWARD

In the 5 years since the AfCFTA negotiations were launched, in June 2015, considerable efforts have been made to bring about the commencement of trading. To date, 23 AfCFTA negotiating forums have been held, alongside 16 meetings of the African ministers of trade, and dozens of technical working group meetings. Considerable celebration deservedly surrounded the start of trading under the AfCFTA Agreement on 1 January 2021, yet much work remains if the Agreement is to deliver successfully on all its promises for the development of Africa.

At the technical level, negotiators must work harder to reach an agreement on the remaining aspects of the Agreement, including the small number of unsettled rules of origin, further submissions of tariff schedules of concessions from certain countries and services schedules of concessions. Progress here has continued to falter since the AfCFTA was officially launched by the African Union in the Kigali Declaration on 21 March 2018, the Operational Phase of the AfCFTA was initiated in July 2019, and the start of trading approved under the Agreement as 1 January 2021.12 As noted in the intervention of the Secretary General of the AfCFTA Secretariat at the eighth meeting of the Committee of Senior Trade Officials, the technical finalization of the phase I negotiations is trailing the expectations and ambitions of the African Union Heads of State and Government.

Negotiations for the phase II and III protocols to the Agreement will commence soon. These topics—investment, intellectual property rights, competition policy and e-commerce—may prove difficult and require renewed understanding and compromise among negotiators. Yet they are critical to the modern and comprehensive undertaking that the AfCFTA aspires to be. The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically accelerated the potential of e-commerce in Africa—with online selling and the adoption of new technologies cited as top opportunities by businesses in recent ECA surveys.13

Although 54 African Union member States have signed the AfCFTA Agreement, 40 have ratified it as of July 2021. To be a truly continental initiative, further consultative and technical preparatory and advocacy work is required to bring together each country’s ratification of the Agreement. Beyond ratification, the real hard work of implementation will begin.

State parties will need to take deliberate actions to make the AfCFTA a success and create the necessary enabling environment. With this in mind, ECA will continue to support AfCFTA implementation and related reforms across the continent. ECA is working with 40 African countries or their RECs to prepare AfCFTA implementation strategies. The need for these strategies was expressed by the Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development at the 51st session of the Economic Commission for Africa in May 2018 in Addis Ababa and was reiterated by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union at its 31st session in Nouakchott in July 2018. These strategies identify new opportunities for diversification, industrialization and value chain development and complementary actions needed to overcome the existing constraints to trade and industrialization. The AfCFTA strategies are being drafted through an inclusive and consultative process at the domestic level and therefore reflect the priorities and interests of a range of stakeholders.

ECA has also organized a number of national, regional and continental AfCFTA forums focused on awareness-raising and information-sharing on the content of the Agreement. These forums have targeted a wide range of stakeholders, such as the private sector, civil society, academia and the media. Broadly speaking, stakeholders have indicated a keen interest in engaging in implementation of the AfCFTA Agreement. While the forums contributed to increased understanding among participants of the AfCFTA and its effects, they also demonstrated the need for more targeted engagement and advocacy efforts, including those that reach more remote and vulnerable groups of stakeholders.

Lastly, to ensure that the AfCFTA effectively responds to its primary constituents—the businesses that actually trade across borders in Africa and create most jobs—ECA has begun collecting primary data from trading businesses on the challenges and opportunities lying before them. This information is being packaged within an AfCFTA country business index, to evaluate where policy improvements need to be made to maximize the transformational potential of the AfCFTA.

As demonstrated in the present article, the AfCFTA presents considerable opportunities for Africa. In addition to forming part of the continent’s recovery package in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the AfCFTA can help Africa to rebuild an economy that is more conducive to achieving the aspirations of Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals. Now is the moment to seize these opportunities by concluding the remaining technical work and second-phase negotiations and ensuring comprehensive implementation across the African continent.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

SK helped in the study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. VS supervised the project. JAM and SK formal analysis and writing (original draft) the manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The paper has not undertaken research involving subjects or covering sensitivities requiring of ethical approval.

Footnotes

As of July 2020, 54 of the 55 member states of the African Union had signed the Agreement; only Eritrea had not yet signed and 40 states has ratified the agreement.

Resolution D, para. 1, of the Summit Conference of Independent African States (CIAS/Plen.2/Rev.2), 1963. Available at https://archives.au.int/bitstream/handle/123456789/6646/Official%20Text%20The%20Summit%20Conference%20of%20Independent%20African%20States%20Resolutions_E.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

It is worth noting that the BIAT decision effectively created a continental free trade area as a new step toward the realization of the Abuja Treaty, which itself did not foresee a continental trade area but rather a continental economic area instead created by the merging of regional monetary unions (rather than trade areas) (Gérout et al., 2019).

See AU Assembly Decision on the Launch of Continental Free Trade Area Negotiations, Johannesburg, South Africa, 14–15 June 2015, Doc Assembly/AU/11(XXV), para. 5.

Statement of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat at the 10th Extraordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union on AfCFTA, available: https://au.int/en/speeches/20180321/statement-chairperson-african-union-commission-moussa-faki-mahamat-10th.

Average tariffs faced by exporters within regions calculated with reference group weighted average tariffs based on MAcMap-hs6 2013. For cost estimates of non-tariff barriers, see Olivier Cadot and others, ‘Deep regional integration and non-tariff measures: a methodology for data analysis’, Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities, Research Study Series No. 69 (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva, 2015).

The prices of metals recovered strongly from July 2020, on expectations of stimulus-driven infrastructural demand in large economies, and particularly the faster-than-expected recovery in China, which accounts for around half of the global consumption of metals (World Bank, 2021). Oil prices took longer, returning to their pre-crisis levels only in May 2021. Gold reacted counter-cyclically, realizing its highest ever price on 6 August 2020.

ECA calculations from the UNCTADstat dissemination platform, 2017–2019 averages.

For example, in Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia and Rwanda for Health and in Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe for education, with observed increases over 45%.

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Vera Songwe AU - Jamie Alexander Macleod AU - Stephen Karingi PY - 2021 DA - 2021/12/13 TI - The African Continental Free Trade Area: A Historical Moment for Development in Africa JO - Journal of African Trade SP - 12 EP - 23 VL - 8 IS - 2 (Special Issue) SN - 2214-8523 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jat.k.211208.001 DO - 10.2991/jat.k.211208.001 ID - Songwe2021 ER -