Influence of Women’s Empowerment on Place of Delivery in North Eastern and Western Kenya: A Cross-sectional Analysis of the Kenya Demographic Health Survey

- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.200113.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Women’s empowerment; facility delivery; childbirth; North Eastern and Western Kenya

- Abstract

Background: Labor and delivery under the supervision of a skilled birth attendant have been shown to promote positive maternal and neonatal outcomes; yet, more than a third of births in Kenya occur outside a health facility. We investigated the association between measures of women’s empowerment and health facility-based delivery in Northeastern and Western Kenya.

Methods: Analysis of 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey data was conducted. Logistic regression adjusting for demographic factors, contraceptive use, and comprehensive HIV knowledge was used to assess the influence of the validated African Women’s Empowerment Index-East (AWEI-E) on the likelihood of women’s most recent birth having occurred in a health facility versus at home. Additionally, we explored the mediating effect of contraceptive use on women’s empowerment and health facility-based delivery.

Results: Compared to respondents with low or moderate empowerment scores, those with high empowerment scores were more likely to have given birth at a health facility [odds ratio (OR) = 1.81; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.30, 2.51], although this effect was null in the adjusted model (OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.58, 1.45). Respondents with a recent facility birth (n = 372/836) were more likely to have high household-level wealth (40.9% vs 8.6%, p < 0.001) and use a contraceptive method (44.9% vs 27.4%, p < 0.001) than those without facility-based delivery. Current contraceptive use mediated 26.8% of the effect of empowerment on the odds of facility-based delivery.

Conclusion: Women’s empowerment, and its comprising three domains as measured by the AWEI-E, may be insufficient to overcome barriers to facility-based delivery for women in North Eastern or Western Kenya. High women’s empowerment is strongly associated with current contraceptive use, which may inform pregnancy planning and location of delivery. Alternatively, higher empowered women who delivered at a facility may have been offered contraceptives at the time of delivery. Future research targeting these regions should explore culturally acceptable approaches to broadening access to skilled supervision of labor.

- Copyright

- © 2020 Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Annually, an estimated 303,000 maternal and 2.6 million neonatal deaths occur globally, with an overwhelming majority of these deaths concentrated in low- and middle-income countries [1,2]. While Kenya has seen relative declines in the past 5 years, maternal and neonatal mortality remains high. Currently, the country experiences 362 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and 22 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births [3]. As many as 75% of maternal deaths occur during labor, delivery, and immediately following childbirth [4–6]. Leading causes of maternal mortality in Kenya include hypertension, hemorrhage, and infection [7]. Delivery under the supervision of a Skilled Birth Attendant (SBA) (defined by the World Health Organization as an accredited doctor, nurse, or biomedically trained midwife [8]) has been shown to significantly improve maternal and neonatal outcomes by decreasing maternal and neonatal death [2,4,5].

To promote uptake of SBA services in Kenya, the government implemented a maternity care policy in 2013, which abolished user fees, thus alleviating the financial burden associated with delivery in public health facilities [9]. At the time, 56% of Kenyan women still delivered at home alone or with the assistance of Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) and relatives, contributing to the persistently high national maternal mortality ratio (488 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) [3]. The maternity care policy and political drive around eliminating maternal and neonatal deaths, exemplified by the First Lady’s Beyond Zero Campaign, have contributed to an increase in facility-based deliveries [10,11]. Despite this increase, more than a third of births (37%) of deliveries in Kenya continue to occur at home, where SBA supervision is unlikely to occur [4], and no significant decrease in maternal or neonatal deaths has yet been observed [10]. In many low-income settings, home birth without an SBA is associated with increased complications including limited or no care coordination for high-risk pregnancies or complications during delivery, prolonged or obstructed labor, inability to identify or treat hemorrhage or sepsis, and lack of information on HIV or malaria status [12,13].

Prominent barriers to utilization of facility-based delivery highlighted in literature include structural barriers associated with delivery-related costs and distance to health facilities [14–16]. Low uptake of facility delivery in the context of free maternity care suggests that economic barriers may not be the sole drivers of home births. Furthermore, the high utilization of antenatal care services in Kenya—96% of Kenyan women attend at least one visit and 58% attend four or more times—shows that women can travel to health facilities to access care [3]. While focus has been placed on addressing these macro-barriers, sociocultural barriers also play a role in the underutilization of maternity care and can partially explain low uptake of facility-based delivery [14,16]. Known barriers include fear of HIV-related stigma [17,18] and low perceived benefit, especially among high parity women who have not had—or recognized—labor complications in the past [19–21].

Frequency of interaction with the formal health-care system varies among women with limited health-care decision-making agency [22–24]. Two potential proxy measures for history of interaction with public health and community medical services are current biomedical contraceptive use and ability to correctly identify HIV-related myths that are dispelled in formal and informal health education interactions. However, the extent to which these indicators or others influence women’s empowerment level or their likelihood of engaging with pre- or perinatal maternity services in North Eastern and Western Kenya is unknown.

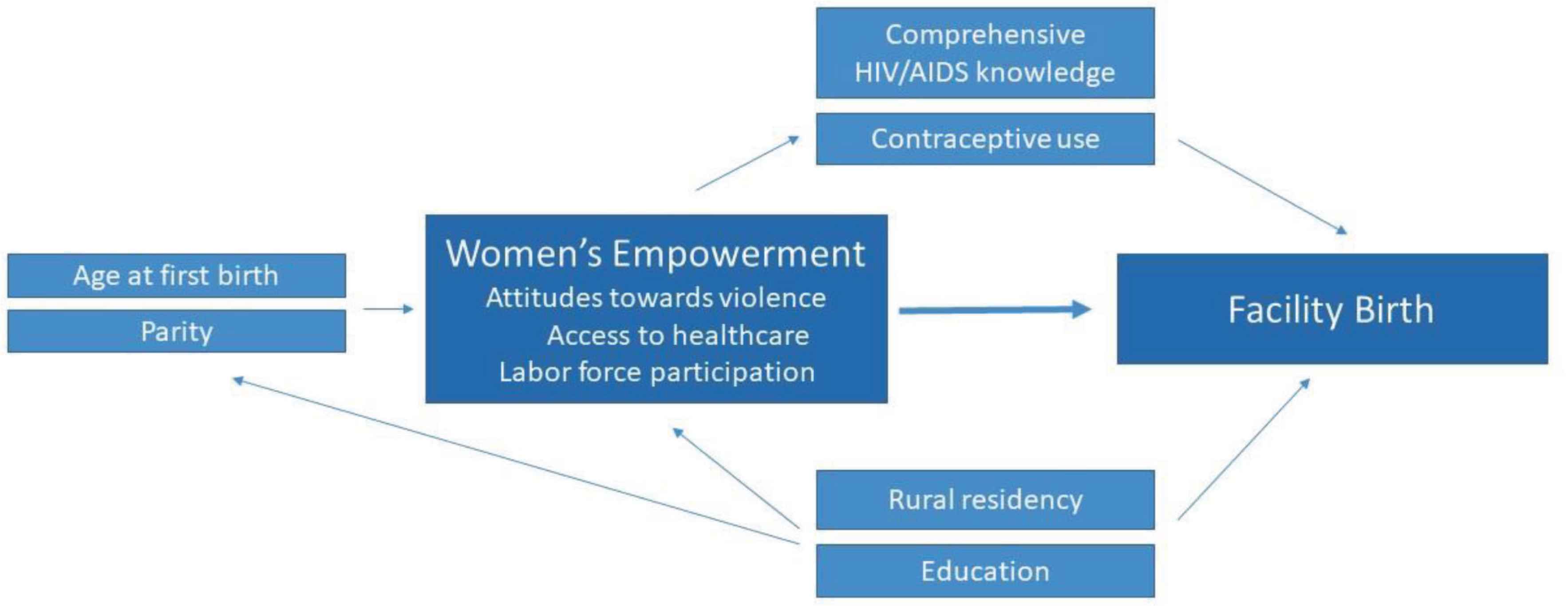

A recently validated instrument, the African Women’s Empowerment Index (AWEI), uses three distinct domains of women’s empowerment for East Africa (AWEI-E), which it defines as “a multifaceted process of change that involves individual and collective awareness, behavior, institutions, and outcomes embedded in distinct social and cultural contexts” [25]. The validated instrument was informed by previous literature on factors contributing to women’s empowerment and can be used to associate women’s empowerment with other health and social indicators such as birth outcomes. The AWEI-E has three domains (i.e., latent traits) that estimate women’s empowerment as self-reported by women in the population of interest: attitudes toward violence against women, labor force participation, and access to health care.

The ability to make health-related decisions and the level of a woman’s empowerment have also been shown to be indicators of utilization of health services [26,27]. However, this potential barrier has not been well established in North Eastern or Western Kenya (Figure 1). Thus, the purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the role of women’s empowerment in the utilization of health-care facilities for labor and delivery among women in Western and North Eastern Kenya, where most maternal and neonatal deaths occur in the country [6]. We used the AWEI to identify which, if any domains of women’s empowerment are associated with the odds of facility-based birth among Kenyan women at high risk for maternal mortality.

Conceptual framework of women’s empowerment, likelihood of a facility birth, and potential covariates relating to female participants in the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey based on domains of the African Women’s Empowerment Index-East.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Setting

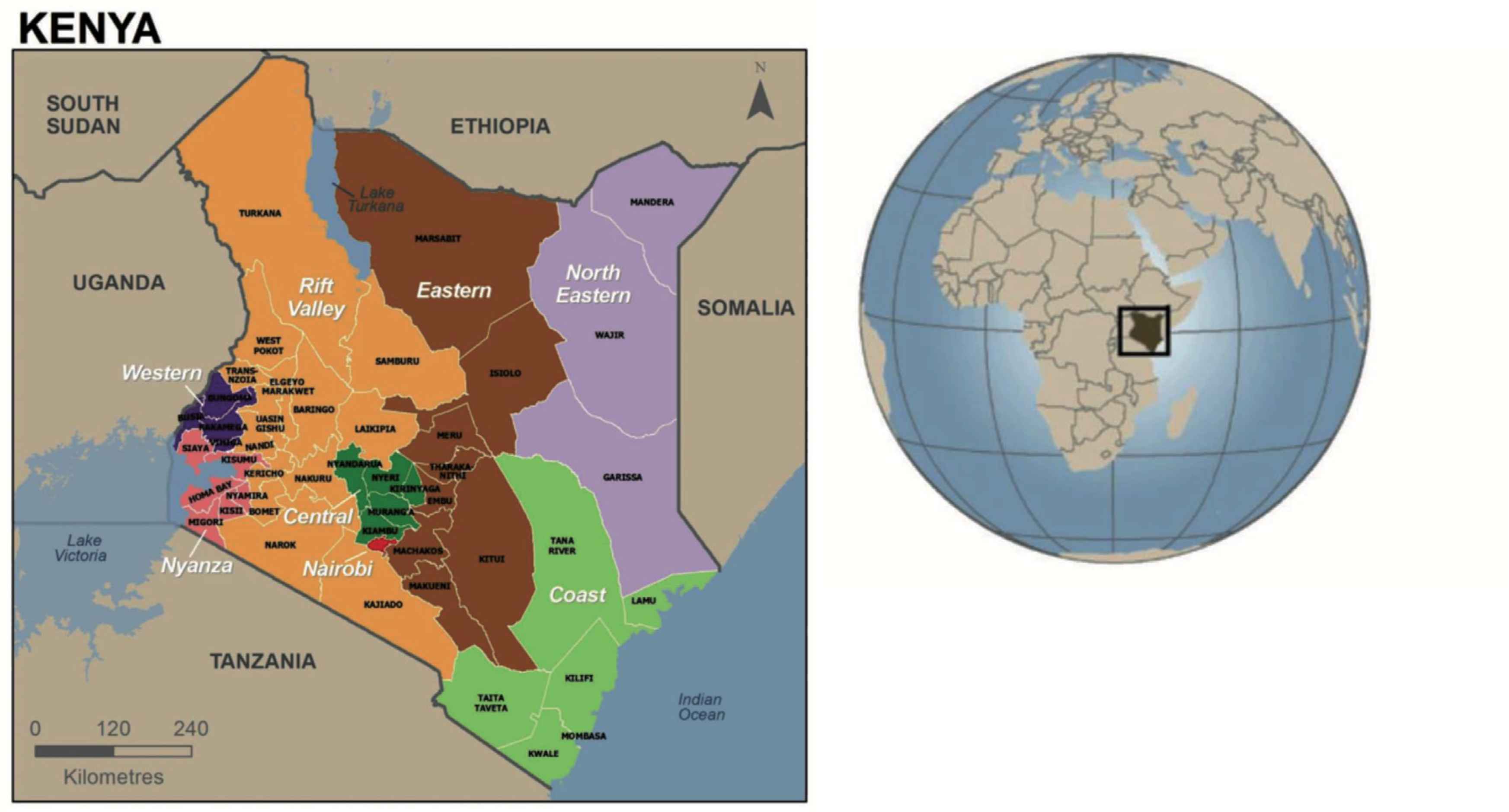

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Within Kenya, 99% of maternal deaths occur in just 15 counties [28]. The counties of North Eastern Province (82.2% rural) have the highest rates of maternal mortality by far (up to 3700 deaths per 100,000 live births). Among provinces with comparable population density and rurality (i.e., without a major city), Western Province (83.6% rural) was selected as a comparator given that the overall maternity mortality ratio for its counties is far lower (up to 800 deaths per 100,000 live births), yet still much higher than the national ratio (362 deaths per 100,000 live births) or the global ratio (210 per 100,000 live births). Furthermore, women in the North Eastern and Western regions deliver at health facilities at even lower rates than the national average (29.3% and 47%, respectively, vs 63% nationally) [28–30]. These two regions were, therefore, purposefully selected for analyses with the rationale that addressing low maternal attendance at health centers for deliveries here could significantly influence national mortality rates.

The Western region borders Uganda to the west (Figure 2). People in Western Kenya are primarily ethnically Luyah and engage in subsistence or low-income farming. Many western Kenyans live or work seasonally in Kakamega. In North Eastern Kenya, which is primarily composed of subsistence-farming Somali tribes, female genital mutilation is practiced nearly universally (97.5%) [29], thus increasing women and girls’ risk for maternal death [3,31]. In addition, early marriage and early sexual debut (i.e., age 14 years or younger) [32] for girls in both regions increase risk for early pregnancy and negative delivery outcomes, including obstructed labor [33].

Map of political regions of Kenya from 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey [3].

2.2. Data Collection

We performed a secondary analysis using the 2014 Kenya DHS, which is a nationally representative, household-level, cross-sectional survey [34]. Participants respond to a comprehensive survey on health, behavior, and development indicators and complete additional submodules if randomly selected. Data for DHS are collected by in-country staff using standardized protocols described elsewhere [35]. Collected data include demographic information on health and social experiences, education and literacy measures, as well as health-related perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes. The data sets for Kenya DHS and those from other participating countries are publicly available to researchers on request [https://dhsprogram.com]. The University of Arizona institutional review board considers the de-identified secondary data from DHS to be exempt from human subjects review.

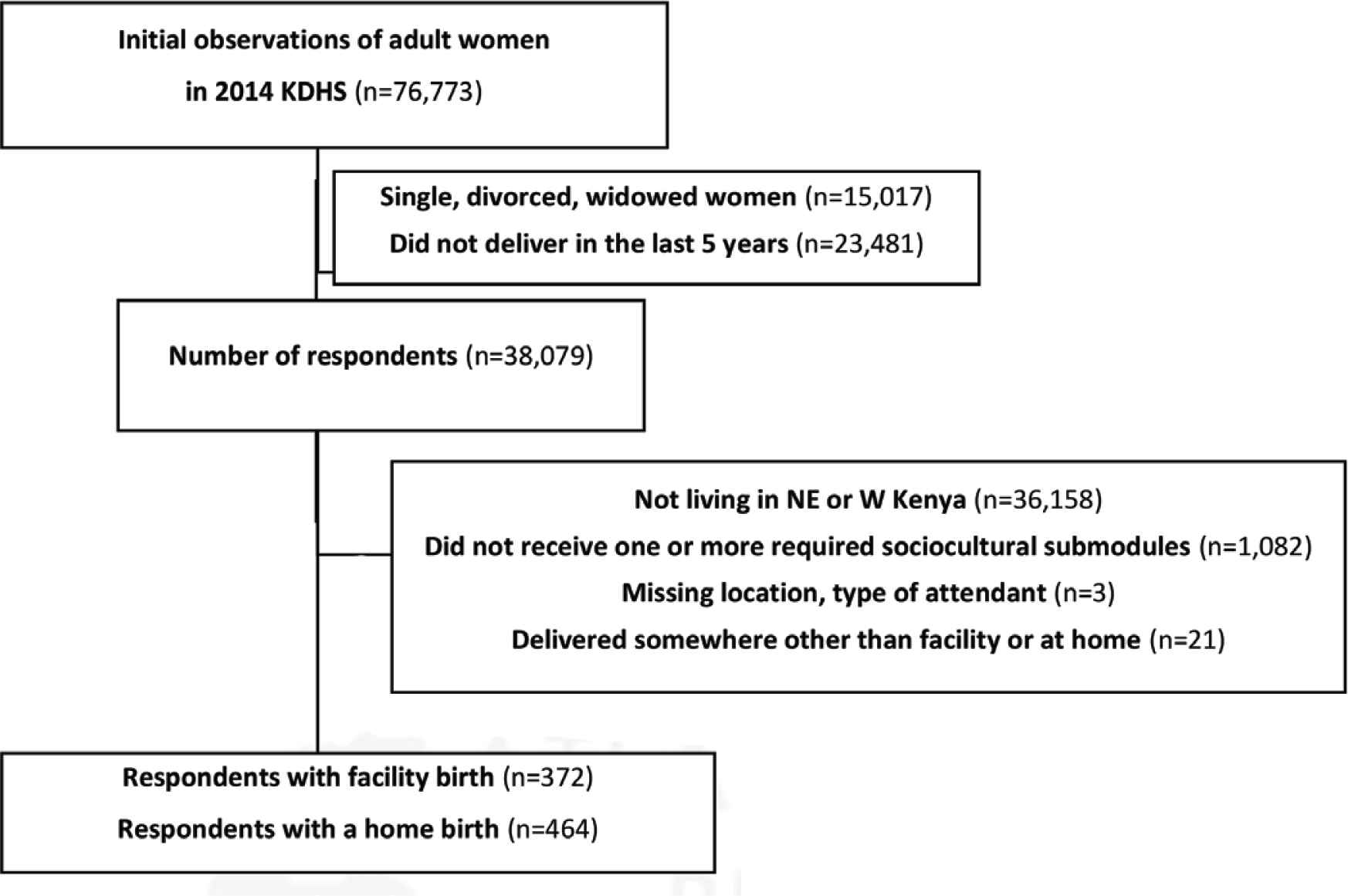

We limited our sample to women residing in Western or North Eastern Kenya who were married or cohabiting (living with a man as if married), who had given birth at least once in the past 5 years either at home or at a health facility, and who received all apposite submodules that contribute to the AWEI (Figure 2). Single, divorced, and widowed women did not qualify to receive all submodules of interest because the AWEI-E was limited to women married or cohabitating women; these women were therefore excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Primary outcome

The primary outcome was location of delivery, which was dichotomized as facility-based birth (i.e., any health center, mission, or hospital) or home-based birth. Location of delivery was limited to respondents’ self-report of their most recent live birth in the past 5 years.

2.3.2. Exposure variable

Women’s empowerment was operationalized using the domains found to be valid for East Africa as per the AWEI-E: labor force participation (four items on economic earnings); attitude toward violence (three items on justifications for violence against women), and access to health care (three items on barriers to seeking care). Total empowerment was the sum of respondents’ scores on each of these three factors and was categorized as low (0–6), moderate (7–13), or high (14–19), with higher scores indicating higher empowerment. We additionally considered each of the three empowerment domains independently relative to the primary outcome. Each domain was placed into two or three categories based on the distribution of response scores. Items included in each subscale as well as categorization cutoffs are available in Appendix A.1.

2.3.3. Controlling variables

Covariates selected for use in a prespecified adjusted model were based on scientific literature related both to women’s empowerment and maternal birth outcomes. Characteristics considered were parity (i.e., total births, categorized as 1, 2–5, 5–8, or >8), age at first birth (categorized as <15, 16–20, 21–25, and >26 years), current use of contraceptives (any method vs no method), region of residency (Western or North Eastern Kenya), and education (categorized in years as 0, 1–5, 5–10, and >10). Additionally, comprehensive HIV knowledge was used as a proxy indicator of prior engagement with health literacy efforts and was measured by five common HIV myths: (1) condom use and (2) limiting sex partners are HIV prevention methods; (3) a healthy-looking person can have HIV and that HIV/AIDS cannot be transmitted through (4) mosquito bites or (5) by sharing food (36). Respondents were scored as having low (0–1), moderate (2–3), or high (4–5) knowledge about HIV based on the number of HIV myths they correctly rejected as false.

2.4. Statistical Methods

We first performed descriptive analyses of demographic variables, domains of women’s empowerment, and relevant covariates, with respondents stratified by location of most recent delivery (i.e., facility or home). Appropriate bivariate tests of statistical significance between groups (i.e., t-tests or Pearson’s χ2) were used with significance set a priori as an alpha of 0.05 or less. Exclusions based on missing or outlying data were recorded in the study inclusion flowchart (Figure 2).

Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of facility birth relative to women’s empowerment level. Unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for having given birth in a facility relative to total empowerment and each separate factor of empowerment (attitudes toward violence, labor force participation, and access to health care). Adjusted models included the characteristics previously mentioned except where strong evidence of multicollinearity was observed. Multicollinearity was assessed by a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of greater than 10 among the explanatory covariates selected for the model; a VIF of 10 or greater resulted in exclusion of that covariate. Goodness of fit was estimated for each model using (1) a Hosmer–Lemeshow test for fit where an alpha less than 0.05 signified lack of fit, as well as (2) estimation of a c-statistic for each model. We tested the sensitivity of the unadjusted and adjusted models of total empowerment by limiting the facility birth group to those who gave birth in the presence of an SBA: (1) returning those respondents who did not give birth in a facility or at home (i.e., somewhere else, such as on the way to a facility) back into the sample and coding them as non-facility births as well as (2) recoding those who reported a facility birth but an unskilled birth attendant (e.g., only had a family member in attendance) as non-facility births (Δn = 28). We compared the resulting ORs, c-statistics, and Hosmer–Lemeshow estimates with the corresponding results from the previously described primary analysis. All analyses were performed in Stata 15 (College Station, TX, USA).

To investigate the hypothesized mediating role of frequency of interaction with formal health services on likelihood of facility-based birth, we conducted an exploratory analysis of the significance of the relationship between the primary predictor (empowerment), the mediator (contraceptive use as a proxy for interaction with formal health services), and the outcome (facility-based birth) (Figure 1) using appropriate regression models [37]. We tested the magnitude of the indirect effect by computing the product of the coefficients for contraceptive use and empowerment level [38]. We performed 1000 bootstrap iterations with resampling to estimate the standard error [39]. While comprehensive HIV knowledge may also potentially indirectly affect the relationship between empowerment and odds of facility birth, it was excluded from this exploratory analysis, given the exploratory nature of this estimate (self-reported knowledge) as well as lack of information about respondents’ own HIV statuses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Description of Participants

Of the 836 included respondents, most (88%) were married (vs cohabiting), multiparous (with those who gave birth at home more likely to have more total births), and had moderate to high comprehensive knowledge of HIV (Table 1, Figure 3). Those respondents reporting a facility birth were more likely to have high socioeconomic status (40.9% vs 8.6%, p < 0.001) and to use a modern form of contraceptive (44.9% vs 27.4%, p < 0.001). Additionally, the proportion of respondents in each of the two provinces of interest who gave birth in a facility versus at home was significantly higher in Western versus North Eastern Kenya (61.3% vs 38.7%, p < 0.001). Only 3% of respondents with a home birth indicated that an SBA such as a doctor or nurse was present at the time of delivery; the majority of home births (73.9%) were attended by a TBA.

| Characteristic | Facility birth (n = 372) | Home birth (n = 464) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age at interview (years) | 28.7 (6.3) | 30.5 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Age at first birth (years) | 19.9 (3.6) | 19.1 (3.2) | <0.0001 |

| Parity (number of births)a | |||

| 1 | 80 (21.5) | 31 (6.7) | |

| 2–5 | 222 (59.7) | 248 (53.5) | |

| 5–8 | 54 (14.5) | 147 (29.8) | |

| >8 | 16 (4.3) | 38 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Women’s empowerment scoresb | |||

| Attitudes toward violence (range 0–4) | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.2) | 0.1655 |

| Access to health care (range 0–3) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.0 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Labor force participation (range 0–12) | 4.0 (4.6) | 3.2 (4.4) | 0.02 |

| Median (interquartile range) | Median (interquartile range) | ||

| Total education (years) (range 0–15) | 8 (0, 10) | 1 (0, 7) | <0.0001 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | 81 (21.8) | 271 (58.4) | |

| Mid | 139 (37.4) | 153 (33.0) | |

| High | 152 (40.9) | 40 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Western Kenya | 228 (61.3) | 201 (43.3) | |

| North Eastern Kenya | 144 (38.7) | 263 (56.7) | <0.001 |

| Married | 327 (87.9) | 413 (89.0) | 0.99 |

| Lives in Rural area | 169 (45.4) | 389 (83.8) | <0.001 |

| Current use of contraceptivesb | |||

| Modern | 167 (44.9) | 127 (27.4) | |

| Traditional | 2 (0.5) | 7 (1.5) | |

| None | 203 (54.6) | 330 (71.1) | <0.001 |

| Type of birth attendant | |||

| Health professional (doctor or nurse) | 362 (97.3) | 15 (3.2) | |

| Traditional birth attendant | 1 (0.2) | 343 (73.9) | |

| Relative/friend | 8 (2.2) | 71 (15.3) | |

| No one | 1 (0.3) | 35 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledgec | |||

| Low | 14 (3.8) | 64 (14.4) | |

| Moderate | 91 (24.6) | 167 (37.4) | |

| High | 265 (71.6) | 215 (48.2) | <0.001 |

Significance tested using t-test or chi-square; missing data rates less than 1% for all variables.

Range 1–18.

Range 0–19, with higher scores implying more empowerment, using the African Women’s Empowerment Index (Asaolu et al., 2018). Modern: pill/IUD/injection/condom/female sterilization; Traditional: periodic abstinence/withdrawal/lactational amenorrhea.

Scored 0–5 as knowing (1) condom use and (2) limiting sex partners are HIV prevention methods, (3) a healthy-looking person can have HIV, and that HIV/AIDS cannot be transmitted through (4) mosquito bites or (5) by sharing food; low knowledge is a score of 1 or less; moderate knowledge is a score of 2 or 3; high knowledge is a score of 4 or more. No covariate was missing more than 5% of data.

SD, standard deviation; IUD, intra-uterine device.

Descriptive statistics of cross-sectional study sample stratified by women’s delivery location using the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey based on domains of the African Women’s Empowerment Index-East

Flowchart of inclusion criteria prior to analysis of the influence of women’s empowerment on delivery location as estimated using the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) based on domains of the African Women’s Empowerment Index-East.

3.2. Primary Analysis Results

Respondents with low or no reported barriers to accessing health care had higher odds of giving birth in a facility in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (unadjusted OR = 2.65, 95% CI = 2.01, 3.48; adjusted OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.18, 2.32). For the other two subscales (labor force participation and attitudes toward violence) as well as for the total measure of women’s empowerment, no estimated odds of facility birth were statistically significant after adjustment. Although not statistically significant, higher total empowerment and labor force participation appeared to reduce odds of facility birth in the adjusted models even though they were associated with increased odds of facility birth in the unadjusted models (Table 2). Models of unadjusted odds all demonstrated lack of fit following the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (i.e., p < 0.05). Total education was highly multicollinear with other predictors of interest (namely, region of residence) and therefore excluded from the adjusted model.

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | ||

| Low empowerment (378) | Reference | — |

| Moderate empowerment (225) | 1.49 (1.07, 2.08)* | 1.07 (0.71, 1.63) |

| High empowerment (233) | 1.81 (1.30, 1.51)*** | 0.92 (0.58, 1.45) |

| C-statistic | 0.5683 | 0.7992 |

| Violence against women (n) | ||

| High acceptance (275) | Reference | — |

| Low acceptance (561) | 1.22 (0.92, 1.62) | 1.07 (0.76, 1.52) |

| C-statistic | 0.5221 | 0.7982 |

| Labor force participation (n) | ||

| No participation (506) | Reference | — |

| Low or moderate participation (221) | 1.34 (0.98, 1.84) | 0.69 (0.45, 1.09) |

| High participation (109) | 1.57 (1.04, 2.38)* | 0.79 (0.46, 1.34) |

| C-statistic | 0.544 | 0.8010 |

| Access to health care (n) | ||

| High or moderate barriers (403) | Reference | — |

| Low or no barriers (433) | 2.65 (2.01, 3.48)*** | 1.65 (1.18, 2.32)* |

| C-statistic | 0.619 | 0.8030 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Adjusted for parity, age at first birth, rural vs urban residency, province of residency (Western or North Eastern), use of contraceptives, and cumulative HIV knowledge.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Factors associated with likelihood of giving birth in a clinic setting versus at home relative to women’s empowerment as estimated using the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey based on domains of the African Women’s Empowerment Index-East

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis Results

Sensitivity of the adjusted and unadjusted models was estimated by redefining facility birth as limited to women who gave birth under the supervision of an SBA, as described in Section 2, which added 28 participants to the at-home birth group. With this revised definition, no practically or statistically significant changes in ORs, CIs, or model fit were observed for any of the models (Appendix A.2).

3.4. Exploratory Analysis Results

The exploratory analysis of the mediating effect of contraceptive use (as a proxy for interaction with formal health services outside pregnancy) on odds of facility birth found statistically significant relationships between all covariates considered (i.e., total empowerment level in three categories, contraceptive use, and facility birth) where no third factor was controlled or held constant, which supports the mediational hypothesis. Using the product of coefficients approach, we estimated that 26.8% of the total effect of empowerment on likelihood of facility birth is indirect via contraceptive use. Following a bootstrap analysis with 1000 repetitions, we found the coefficient of the indirect effect of contraceptive use to be statistically significant in the unadjusted model (β = 0.084, SE = 0.026, bias corrected 95% CI = 0.038, 0.14). Coefficients relative to categorized empowerment levels are described in Appendix A.3.

4. DISCUSSION

Most maternal deaths can be prevented through skilled supervision of labor, yet barriers to selection of a facility-based birth where SBAs work are not fully explained by economic, systemic, or access barriers [14–16]. Consistent with previous studies of women’s empowerment and health-care decision-making, we found that access to care was a strong driver of facility birth [40,41], yet the other anticipated domains of women’s empowerment (attitudes toward violence and labor force participation) did not influence the odds of facility-based birth after adjusting for other covariates.

Less than 4% of our population who gave birth at home reported having a doctor or nurse (i.e., SBA) in attendance, although this is likely specific to Kenya and its health infrastructure. This supply-driven approach, which functionally requires women to select facility-based birth in order to access an SBA, may not be culturally appropriate for all Kenyan women and may partially explain why rates of home births (and subsequent use of unskilled birth attendants) remain high for North Eastern and Western Kenya relative to the national rate [29]. While the unadjusted ORs for women’s total empowerment, high labor force participation, and low or no barriers to accessing care appeared to have statistical significance, measures of model performance implied lack of fit. However, a known problem is that large sample sizes increase the likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis for minor deviations in lack of fit [42].

The finding of mediation by contraceptive use was unexpected yet supports our result that better access to health care increases odds of selection of facility birth. While one possible explanation is that women with higher empowerment are more likely to use contraceptives and therefore plan their pregnancies and deliveries [43], it is also possible that higher empowered women who gave birth at a facility were offered contraceptives at the time of delivery and have been using them since. While the results of this study support the notion that health care-seeking behaviors are especially complex in low-resource settings [40,44,45], they may also highlight limitations of the survey tool to measure the latent traits in question. This is exemplified by the unexpected finding that over two-thirds of respondents did not participate in any form of incoming-generating labor (i.e., received 0 out of possible 12), implying that the AWEI-E may lack items that are easier to endorse (e.g., reflect other-valued labor) or scale options that appropriately differentiate women’s labor in North Eastern and Western Kenya.

This study had several key limitations. First, the nature of the items in the AWEI-E precluded the inclusion of women who were single, divorced, or widowed, even though these individuals may have different empowerment compared to their married peers and still experience pregnancy and delivery. Second, the cross-sectional nature of DHS prevents measurement of temporality with regard to contraceptive use and facility birth. Third, all responses were self-reported and may have been subject to up to 5 years of recall bias. Finally, use of logistic regression may have oversimplified the distinctness of empowerment (and its three unidimensional subdomains) from other predictors included in the adjusted model, which are likely somewhat reciprocal. Given the unexpected finding of a mediator (contraceptive use), approaches such as structural equation modeling may more appropriately reflect the complexity of the model and reduce measurement error [46].

This study found that only the access to health-care domain of women’s empowerment is associated with facility-based delivery when other key factors such as contraceptive use are accounted for. Thus, access to health care is a better predictor of facility-based delivery than the other domains of women’s empowerment (i.e., attitudes toward violence or labor force participation) for women in North Eastern or Western Kenya. Future research and interventions targeting these two regions of Kenya should explore culturally acceptable approaches to promoting access to, and acceptance of, SBA supervision of labor.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

JJC and IOA conceptualized the project and conducted initial background research, EJA and MLB planned and conducted the formal analysis and validation, EJA and JE interpreted the results, EJA led the writing (original draft and editing) of the manuscript, and JE and MLB supervised the project. All authors approved the final article.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AWEI,

African Women’s Empowerment Index;

- AWEI-E,

African Women’s Empowerment Index: East;

- CI,

confidence interval;

- DHS,

Demographic and Health Survey;

- FGM,

female genital mutilation;

- HIV/AIDS,

human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome;

- OR,

odds ratio;

- SBA,

skilled birth attendant;

- SD,

standard deviation;

- TBA,

traditional birth attendant;

- VIF,

variance inflation factor.

APPENDIX A

| Unadjusteda | Adjustedb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Standard errorc | p | β | Standard errorc | p | |

| Indirect effect of contraceptive use given moderate empowerment | 0.029 | 0.0097 | 0.003 | 0.00055 | 0.0018 | 0.760 |

| Indirect effect of contraceptive use given high empowerment | 0.055 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.00074 | 0.0026 | 0.781 |

| Total indirect effect of contraceptive use | 0.084 | 0.026 | 0.003 | 0.0013 | 0.0037 | 0.728 |

| Total direct effect of contraceptive use | 0.159 | 0.073 | 0.029 | – | – | – |

Notes: While comprehensive HIV knowledge may also potentially indirectly affect the relationship between empowerment and odds of facility birth, it was excluded from this analysis given the exploratory nature of this estimate as well as lack of information about respondents’ own HIV status.

Mediating relationship of contraceptive use on empowerment level and facility birth.

Mediating relationship of contraceptive use on empowerment level and facility birth considering for parity, age at first birth, rural vs urban residency, province of residency (Western or North Eastern), use of contraceptives, and cumulative HIV knowledge.

Bootstrap error calculated using 1000 repetitions.

Estimated mediating effect of contraceptive use on odds of giving birth in a clinic setting versus at home relative to women’s empowerment as estimated using the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey based on domains of the African Women’s Empowerment Index-East

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | ||

| Low empowerment | Reference | – |

| Moderate empowerment | 1.52 (1.09, 2.13)* | 1.06 (0.70, 1.61) |

| High empowerment | 1.71 (1.23, 2.38)** | 0.85 (0.55, 1.34) |

| c-statistic | 0.5635 | 0.7905 |

| Violence against women | ||

| High acceptance | Reference | – |

| Low acceptance | 1.18 (0.88, 1.58) | 1.11 (0.79, 1.56) |

| c-statistic | 0.5178 | 0.7886 |

| Labor force participation | ||

| No participation | Reference | – |

| Low or moderate participation | 1.32 (0.97, 1.82) | 0.65 (0.42, 1.01) |

| High participation | 1.43 (0.95, 2.15) | 0.72 (0.42, 1.22) |

| c-statistic | 0.5384 | 0.7929 |

| Access to health care | ||

| High or moderate barriers | Reference | – |

| Low or no barriers | 2.56 (1.93, 3.3)** | 1.62 (1.16, 2.27)** |

| c-statistic | 0.6147 | 0.7929 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval;

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

Adjusted for parity, age at first birth, rural vs urban residency, province of residency (Western or North Eastern), use of contraceptives, and cumulative HIV knowledge.

Sensitivity analysis of odds ratios of likelihood of giving birth in a clinic setting versus at home relative to women’s empowerment as estimated using redefined criteria for home-based/unskilled birth attendance (Δn = 28) via the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey based on domains of the African Women’s Empowerment Index-East

| Indicators for economic (labor force participation) dimension: No participation: 0 Low participation: 1–9 Moderate or high participation: 10–12 |

|

| Respondent’s occupation | 1 Works for a family member |

| 2 Works for someone else | |

| 3 Self-employed | |

| Type of earning from respondent’s work | 1 Paid in-kind only |

| 2 Paid cash and in-kind | |

| 3 Paid in cash only | |

| Seasonality of respondent’s occupation | 1 Works occasionally or seasonally |

| 2 Works all year | |

| Income ratio | 1 Partner does not bring in any income |

| 2 Earns less than partner | |

| 3 Earns about the same as partner | |

| 4 Earns more than partner | |

| Unemployed | 0 |

| Indicators for sociocultural (attitudes toward violence) dimension High acceptance of violence: 1–2 Low to moderate acceptance of violence: 3–4 |

|

| A beating is justified if a wife: | 1 No |

| —Neglects children | 0 Yes or don’t know |

| —Goes out without telling partner | |

| —Argues with husband | |

| Indicators for health (access to health care) dimension High or moderate barriers to access: 1–2 Low or no barriers to access: 3 |

|

| Receiving permission before getting medical help | 1 No |

| 0 Yes | |

| Having money for health care | 1 No |

| 0 Yes | |

| Distance to health facility | 1 No |

| 0 Yes | |

| Not wanting to go to health facility alone | 1 No |

Domains for empowerment of women in East Africa as determined by the African Women’s Empowerment Index [25]

Footnotes

Data availability statement: The data sets for Kenya DHS and those from other participating countries are publicly available to researchers on request [https://dhsprogram.com].

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Elizabeth J. Anderson AU - Joy J. Chebet AU - Ibitola O. Asaolu AU - Melanie L. Bell AU - John Ehiri PY - 2020 DA - 2020/01/30 TI - Influence of Women’s Empowerment on Place of Delivery in North Eastern and Western Kenya: A Cross-sectional Analysis of the Kenya Demographic Health Survey JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 65 EP - 73 VL - 10 IS - 1 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200113.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.200113.001 ID - Anderson2020 ER -